⑥ Enduring Dreams: a note on cinematic time (sections 14 – 15)

INFINITE REGRESS

Once I conceive consciousness in cinematic terms, rather than admit to the mechanism being simply out of reach, it’s easy to picture myself being a passive observer of what passes before me as if on a screen. It is perhaps more desirable but this opens the possibility of there sitting in the cinema of myself yet another observer who is the recipient of my own observations of the screen watching the film I am projecting for myself from in myself. Further little observers, each one stuck in the cinema of sensation of the one before can be imagined in a reduction that resembles the kind of paradox Zeno uses to challenge the naturalistic conception of time.

The paradox is as well of the sort, notwithstanding the fact I don’t, that Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson see in Russell’s answer to Bergson’s answer to Zeno because once one observer comes between myself and my sensation there can come an infinite number. It follows in turn that because of the endless line of mini me watchers that I never get to see what I see. The perception never reaches sensation.

Sense never gets to arrive at consciousness. The arrow never reaches its target. It requires an equally infinite amount of time not ever finally to arrive because there is no end and no next except that of its duration, of the arrow in flight, of light first projected then in endless transmission. The medium for this transmission is the air, is consciousness and is time but for the cinematic image in particular the light bearing the image is the same as the light that makes it.

For something that goes so fast it goes so slowly as never to arrive and seems that nothing can go more slowly. If Russell’s solution is applied to this paradox we repeat the doubling up of cinematic time by thought. Later in their introduction to a selection of his writing, Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson say that what is at stake for Bergson is not whether science is wrong about time but whether the time of science and the time of cinema and of the cinematograph are the same.

TAKING BERGSON TO THE CINEMA

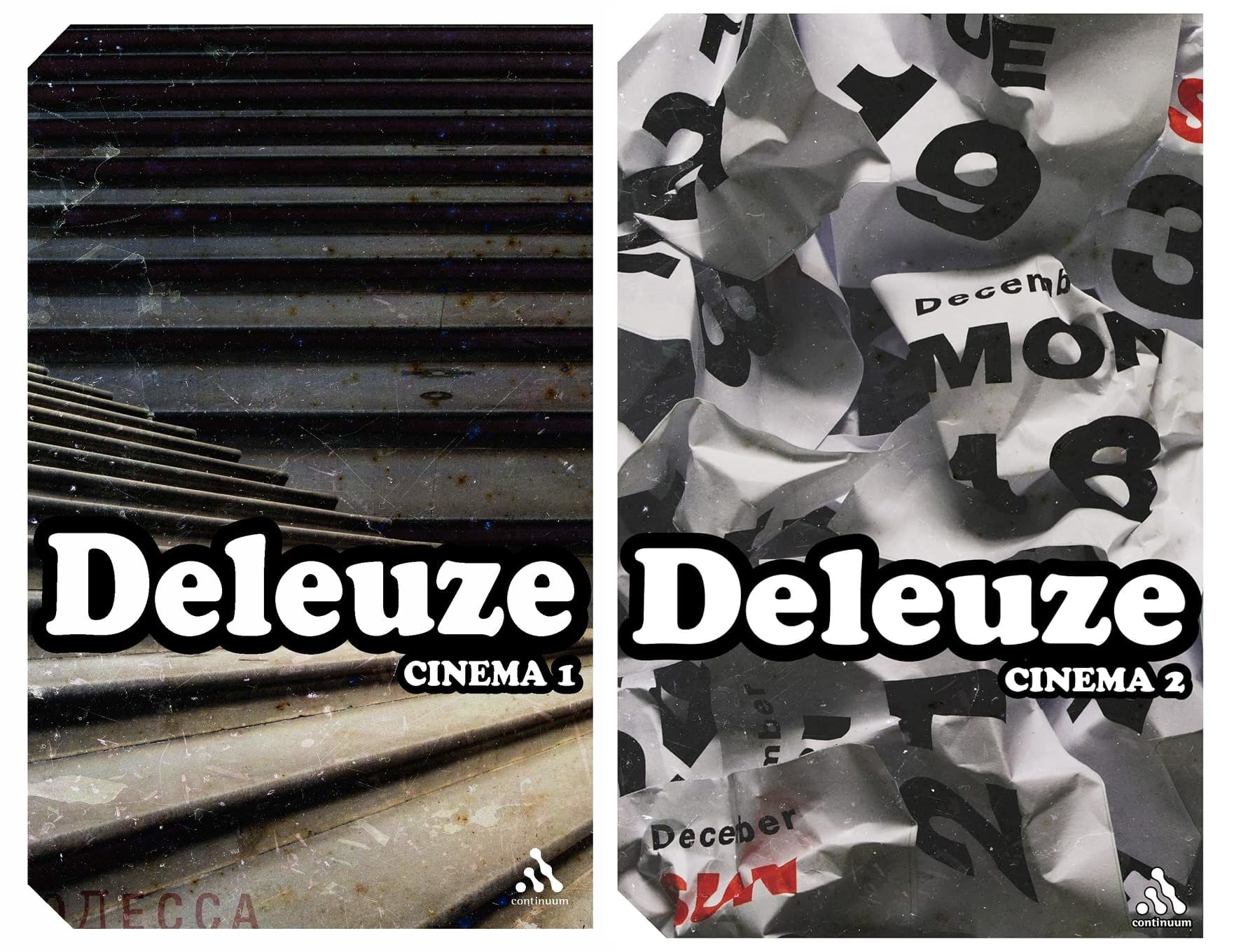

In his books on cinema, written late in his philosophical career, it is said Deleuze takes Bergson to the cinema. Bergson on his own behalf has little to say about cinema but Deleuze is not about trying to reconstruct what he would say if he had given it more thought. He is not rehabilitating cinema in Bergson’s eyes. He is rehabilitating Bergson in cinema’s. He is setting Bergson in philosophical light of cinematic time.

Deleuze does so in such a way that the elision between the time of science and the time of cinema falls back both into the historical and the cinematic background that is the background of cinema’s own particular history. For him this happens before and he writes after. Neither does philosophy do cinema for Deleuze nor is one applied to the other. For him, cinema does philosophy. He tries to show what it thinks in philosophical terms.

I am trying to show what cinema thinks in cinematic terms, specifically in terms of cinematic time or of the time cinematic time is imagined to be. The history of cinema has value for this account because it shows how we wind up with an image of time that is drawn from cinema. For me Bergson’s value is in the persistence of the problems with spacetime he deals with and also in the problem he poses for his readers today.

The problem is exactly that he doesn’t have much to say about cinema and that we don’t find in Deleuze, in his books on cinema at least, what he could have said. Bergson’s examples, his images for duration are not just old-fashioned they are inadequate to the one that Russell illustrates for time. Bergson talks about a melody.