⑦ Enduring Dreams: a note on cinematic time (sections 16 – 18)

DURATION HAS THE QUALITY OF A MELODY

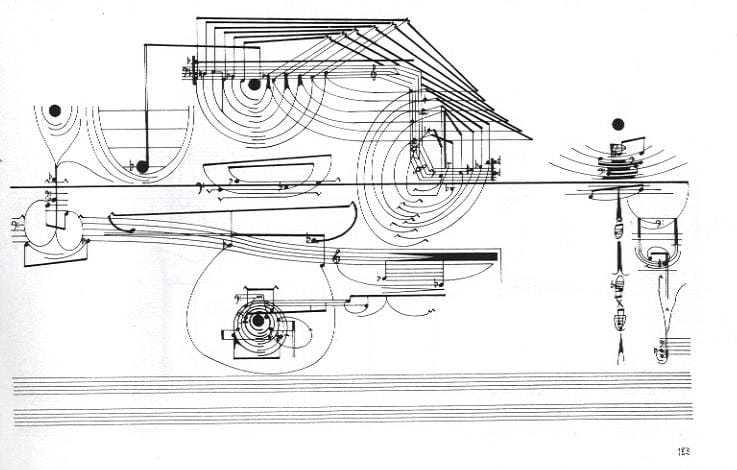

If it glitches out it is no longer that melody. Any alteration in the intervals of time brings about qualitative change. The melody no longer makes sense or it makes a new kind of sense. He talks about a bell tolling.

He hears it ring a number of times but he needn’t count them. Without attending to number he gets a sense of the number. From its qualitative duration he hears how many times it rings.

Switching to cinema Bergson does consider the effects of slowing down motion to show on film changes in natural processes that happen too quickly for the eye. He talks about film’s usefulness for science because of this. He doesn’t seem to see what’s coming, that film can be so compelling as to displace all other images of time and the assumptions made about them, that it will induce the displacement of metaphysical by cinematic assumptions.

This is the advent of cinema, the displacement by cinematic assumptions of assumptions made about time. To say they are metaphysical is to point to the elision of one to the other being unexamined. It is unconscious and where it is a conscious choice, for example, for the sake of example, gives negative proof. It covers for what is not there and only confirms the tendency, having been naturalised, being natural.

I can appreciate these examples of Bergson’s, the melody, the tolling bell, intellectually but I don’t automatically understand them, so the question is what do I automatically understand. What do I think we automatically understand? If we confine ourselves to operations in cinematic time we can’t understand Bergson.

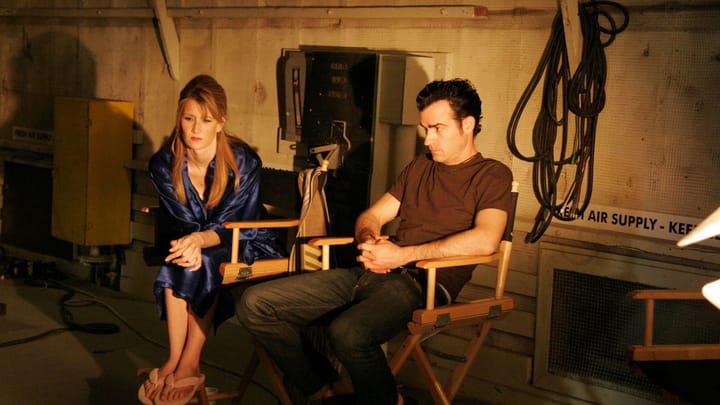

THE IMAGE AND THE INTERVAL

We can understand him least when, by saying the brain is an image among images, he is closest to us. Intellectually we can come to appreciate him. To make sense of him we can remind ourselves that the image he is talking about is not a representation and it is not a representation either subjectively or objectively, neither in the mind nor in the world.

We can learn him and build up, piece by piece, the parts of the puzzle we do understand finally to complete the picture. It will take time, or we can use Bergson’s own method, of intuition. To intuit invokes a different sense of time.

Intuition goes to the interval that breaks the automatism of our continuous apprehension of the world, and of ourselves. When thinking about what I do or don’t automatically understand I thought, I don’t understand myself. I come to understandings with myself.

There is room for negotiation that sometimes involve placing constraints on myself. I constrain my behaviour and emotions to what I prefer, for myself and what I prefer to project to the world but, if I am honest, my own self-understanding seems to have more to do with reconciliation and accepting that I don’t know and what I don’t know. The flaws I find after all are in the eyes of others not flaws, whereas pride, pride is the classical flaw in character.

Humility towards oneself seems too positive to me, too much of an action, while passivity is too close to indifference. I tend to keep openminded, or I would like to think so, towards myself and what it represents, to keep open the material space that I occupy. This bodily space is probably what I least understand and to see it in the aspect of mortality, of either sex or death, suggests to me a reductive view.

I prefer to see myself in the aspect of an interval. It’s not necessarily the one where we get ice-cream and it need not be the one where we leave the cinema but it does break open what I have here been calling cinematic time. A break occurs in the continuity of apprehension either of the mechanism, for example a clock or cinematograph that is both projector and camera, or our own, the apprehension of the subject.

The idea of a continuous time lends itself naturally to the image of a mechanism for registration and playback of the moving image, the break, the interval, more naturally to subjective experience. Objective time borrows its sense of automatism and continuity from this image, I have been saying. The subject then takes up the image in its mechanically rendered automatism and continuity and idealises it to render to consciousness what belongs to cinema, the indifferent film of all our personal imagery playing in the cinema of the self.

The stakes are high. They engage scientific and philosophical, physical and metaphysical, materialist and idealist notions of time, of what time is and, by engaging objective scientific notions, empirical notions, of what can be tested for and what measured, also are at stake. This is why it’s important to point to both the mechanism and the subject as each having a time internal to it that is duration.

In neither the subject nor in the cinematograph is there really automatism and continuity. This is an idealisation. It comes from cinema. It takes in the whole field.

If cinema can show us this and we will get to it we should ask what Bergson can show us about cinema. Apart from ice-cream, what is the good of the interval to cinema? Surely the good of it is to show its own continuity of apprehension and its automatism of mechanism in order to assure us of ours, that is in order to give us the impression of a continuity matching real life and to do so without our manual intervention or suspension of disbelief? If the cinema’s continuity and automatism breaks down or our own does, and our own does, it’s not working and we are back in the pathological zone, aren’t we?

Then we are weighting cinema with our own welfare. This also I have been saying. It goes both ways.

“BREAKING DOWN IS PART OF THE VERY FUNCTIONING . . .”

– Deleuze & Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, 1972/1977

First to the subject, when the automatism of its continuous apprehension breaks down it starts working. Outside of any metaphysical pretension to understanding, the work the subject does is to intuit from its surroundings how to adapt itself to them, either to perish or to make use of elements that are there. When the ground falls from below my feet I don’t scramble to find a reason to stand upright. The same is true for intellection, for intellectual apprehension.

When faced with the minimally unfamiliar, the next in a superhero franchise, I can go with the flow. I go with it unless it loses me or I lose it. I’m here concerned with me losing it. It losing me will follow.

I lose it and burst through to the thoroughly unfamiliar. In other words I have not adapted myself in time but I have if it is a matter of duration. An interval opens that is there all of the time.

I had not been aware of it. Now it imposes itself on me. Either all of a sudden or by slowly creeping up, these are the two modes of intuition, that it is instantaneous or follows the contour of the things happening in the film. In the second case I am travelling with a minimal subject, a subject so strung along that it is oblivious of the risk.

When I’m so involved I am oblivious I am following my intuition. In the zone, I am in the interval but what is happening is a detour. A shock may come at the end of it, the shock of lack of recognition, of the failure of recognition.

The film may come to a dead end. The problem it sets, the question it asks, continues. This is there all the time for the adaptation to our surroundings in the interval between what is sensed and its selection.

Elements are selected for their usefulness to us and their selection is largely intuitive. We have familiarised ourselves with it to the degree it does not involve an active effort directed towards trying to make sense of the unfamiliar. The selection is then for an action.

The interval of intuitive activity going on all the time in surroundings we know, in genres we have general knowledge of, Bergson puts down to how elaborate and complex the nervous system is in humans. In it, there is always delay. Even when no intellectual effort is required there is delay between perception and sensation.

Bergson says this is always coloured by affective states, by moods and feelings, and that these as well as the process of making sense are influenced by memory. What contours they are we are following in a romcom is being selected as we go by the states elicited in us by events in the film in connection with our expectation and recognition. Time is so far comfortable, unless the contour should drop away and we find we’ve pinned all our expectations on false promises.

Everything is up in the air. What does this look like? It looks like physical pain insofar as no matter how we try and recoil from it we are thrown back on the body as if, not the emotional journey we were on but, it is the source of discomfort.

Intuition engages memory, emotion and intellection. Intellectual intuition, given the normal run of things, tends to laziness. It tends to take all flows for that flow affecting everything and everyone around while effecting nothing.

Once out of the flow, I’m on my own pressed up against and having to recognise my body as its source. My outer experience goes to inner experience. Outer experience takes a detour through inner experience, experienced as duration.

Now this flow does effect something. It produces inner experience. This inner experience is neither mediated nor reproduced.

It ceases to be the flow of consciousness imagined apart from the body. It ceases to be the flow of film imagined apart from the mechanism. Either one or the other is set in the ideal light of the mechanism to be continuous and automatic.

The automatic flow of consciousness suffers a delay, is detoured by the film, comes up against itself and its own mechanisms in the body of duration. This is not usually the case. Films are usually made to escape the flow of time not in this way but the fact of that escape proves something about the nature of cinematic time. It belongs to duration.

Belonging to duration the time of inner experience and cinematic time are discontinuous. They do not approach time as a substrate. They are not asymptotes to time’s arrow.

The advent of cinema is a challenge to time’s arrow that it meets by assuming it as its own. Time runs from that advent to the point tomorrow it may run out for us. This is not to take no notice of the detour and delay in duration.

Time as the medium in which we swim does not flow. It has oceanic depths. It is even chaotic. Then film comes along and seems to put it in order.