⑦ How Cinema Has Changed Our Minds

or, How Recording Moving Images Has Changed Our Minds

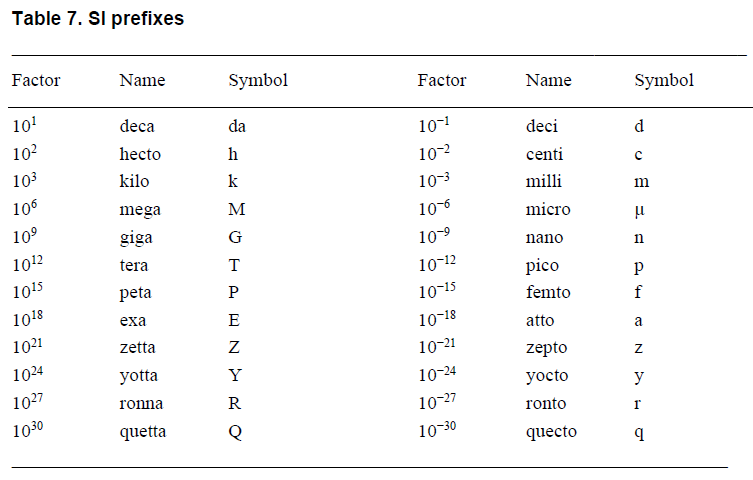

Indirectly, I've heard a reader ask, Where's he heading with these philosophers he's talking about? and, because it's gratifying to be read, I am answering the question. The philosophers I have been writing about are Gilles Deleuze and Henri Bergson, one famous for his philosophy of difference, positively thought, being essential, the other for his philosophy of Durée, sometimes left untranslated. I've been translating it, duration, to make it less exotic, because it's not. It means the time spanned by any measurable length or quantity of time: from a zeptosecond (currently the smallest amount of time measurable), see chart—

—to

years.

The time spanned by any magnitude can in turn be represented as a magnitude, however Bergson maintains that it cannot itself be a magnitude. For experience, we might say subjectively, it must have a quality. Conversely, objectively, it must be a quality.

I am heading to the time spanned by any quantity being represented not by an order of magnitude, mathematically, but cinematically, by a shot, comprising a succession of moving images, which it does, at first. In digital representation we watch at greater or lesser resolution moving images composed of pixels. The point here is of the representation of time versus what time is. To an extent greater than we imagine, mathematical time, however it is represented, whatever symbol is used, has been displaced by cinematic time.

That Deleuze wrote two books on cinema complicates matters, in particular in regard to how time is represented. From a philosophy of difference being the essential we get the cut determining what a shot is. The invention of the shot comes from the practice of inserting cuts between shots, the difference between shots is what is essential and not what is in the shot. This is in fact in cinema history the traditional understanding: the cut defines the shot.

Deleuze's two books on cinema further complicate matters by enlisting Bergson as their primary antecedent so as to speculate on there being a distinct time image. Deleuze's philosophy of cinema comes from the time image as cinema's conceptual creation. It comes about in cinematic practice some time after WWII. In turn, because the time image is a concept Deleuze considers this cinema's gift to philosophy. Cinema invented the time image and philosophy names it as a concept.

I went to Bergson because I didn't understand the time image. He hasn't made it any clearer. I would say that Deleuze's use of him in his work on cinema is the twofold greatest obstacle to understanding Bergson. We might say the obstacle crystallises in the concept of the time image or it fractalises and is, reflected at smaller and smaller scales, en abyme, which is a good enough image for how difficult it is to get to the bottom of it.

- Deleuze puts cinema and Bergson together but leaves out duration.

- Cinema itself obstructs our view of duration—

- BUT—it also proves it! because

- in the shot we experience the span of time it covers as a quality. Unless it's a boring film. If it's a good one, we lose our sense of it taking up of just over 45 seconds for Le Repas de bébé, 1895, a minute or 162 for One Battle After Another, 2025.

- I see it too: that a movie is composed of innumerable cuts as well as shots and it's the combination of the two in cinematic practice that works to suspend our sense of time passing, that is, duration.

Enter Jordan Schonig and cinematic contingency. Schonig's article "Contingent Motion: Rethinking the "Wind in the Trees" in Early Cinema and CGI" came out in Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture in 2018. (It's available on academia.edu.) It overturns the accepted notion of the cut defining the shot. In the shot Schonig finds contingent motion, objects that change states in time completely by the operations of chance. This is how we see the passage of time before it's turned into a story, either by science dealing with causality and emergence, or medicine by dealing with pathology and etiology, or by cinema by dealing with the narrative structures which are supposed to explain it.

When they are not being used to explain it they are being used to explain its appeal, but this appeal Schonig shows at first to have nothing to do with narratives, stories or any kind of progress facilitated by the series of shots and edits, or process. It has at first to do with contingency, which alone explains cinema and defines the shot:

the shot presents contingent motion.

Objects move through successive states in complete detachment from the mechanism driving the film. Neither this mechanism nor the act of cutting defines the shot. What blew the first cinema audience's mind was that the leaves were moving on the trees.

It's just the wind. This they didn't say, because they couldn't see it. They couldn't see it, much as we can't see what moves us from one mental state to another. Cinema and duration share this quality. However one is used to explain the other!

Cinema is used to explain how one state succeeds another in consciousness: it is given a cinematic image. Contingency shows, in the shot, that duration defines and explains the quality shared by mental states and cinema: both are subject to what the philosopher Quentin Meillassoux gives its philosophical credentials as radical contingency, but, he stops there, and I go further.

Once we see that the shot presents contingent motion and that this defines its relation to duration we see why we have the notion of time we do. It is time as perceived by cinema. The problem is how the mind reflects on itself when its mental states are accorded a cinematic reality. Again, we might here invoke—a crystallisation of the problem and its reflection at smaller and smaller scales, as one image reflects on another—the image of the time crystal.*

The simplest way of saying this is that what was contingent motion for the pre-cinematic audience is no longer. Rather, our contingent motion is cinematic. The leaves on the trees may move but we can easily imagine them repeating that movement precisely—on film, and because of film. What had the quality of contingency, of chance, is now nominatively though in fact not really contingent motion. And what time is has changed—contingent motion cinematically described being the fulcrum or hinge for that change.

Much more explanation than I intended. Where I am headed with Bergson and Deleuze and the moving part, the hinge, which I wouldn't have without Schonig, is from how cinema has changed our minds to how our minds have been changed. Cinema unconsciously frames all current discussion of consciousness because it has intrinsically to do with our experience of time, that is, with inner duration. The model we have of networks, of the brain, of what constitutes intelligence, so modelling what AGI might look like and what AI does, of the mind and our mental states, because they are based on time all refer back to the capture of contingency by the cinematic image, the shot.

Bergson is interesting because he doesn't know this. Deleuze almost seems to transpose the two terms, thought and cinema, offering an indirect proof, albeit they only do after the advent of cinema, that they concur. How cinema changed our minds was enable what previously was unrepeatable to be repeated and what previously was irreversible to be reversed: the time in which objects change states. Movement is shorthand for change because we know objects to be determined in space but where they are in space to be contingent. We also know that for science contingency and things moving randomly simply means we haven't . . . seen the wind that moves the leaves.

Bergson describes two lines. One space. One memory. We are clear he is in the mental space.

And he talks about (this is at 59 of Matter and Memory) the immediacy of our surroundings which we perceive and those surroundings which we don't. We don't perceive them. We imagine them, yet imagining them we have difficulty imagining them as anything other than definite and determinate. Space is filled with objects further away than our immediate perception reaches which are definite and determined. In fact we can define the boundary between unperceived and perceived clearly without calling into question the existence of what is distant from us.

When we come to memory we have states, in time, and these have none of the necessity objects have, in space. They are contingent, whereas the objects are determined. And this is regardless of the difference between them being what we don't any more perceive and what we don't yet perceive. Where does the contingency of one and the necessity of the other come from?

For Bergson they are two lines which meet in the present. One goes from the states no longer perceived to those which are; one, from the objects not yet perceived to those which are. And Bergson's assertion that perceived or not prior states exist, just as objects which are presently unperceived, still has validity, but as an argument its validity has changed. The existence of memory is not so contestable as it was for him. The existence of prior states of consciousness in the material of the brain is currently hot property.

It interests me however that Bergson describes the line of memory as contingency. Memories are he writes capricious in how they come to mind. The evolutionary explanation for this is that only those memories bearing on our current actions are needful, and the past can look after itself. It also interests me that Bergson says something I have heard neuroscientists repeat: we are in our characters the sum total of all our past mental states. That who I am to others as to myself is the product of my memories appears incontestable.

We can imagine contingent states. We can imagine states being contingent, such as by the images brought to us by quantum science. Science we are told prefers not to, Einstein preferred not to accept radical contingency. Still, we can imagine contingent states but is this how we imagine memory?

Our past states are rather scenes. Contingency may still operate, since images and whole scenes may come to us for no apparent reason. Like dreams, the meanings of which deriving from their associations, it is, as it has been for a very long time, the work of several industries, psychic and psychoanalytic, to plumb.

It is rare today to hear someone talk about a memory being of a past mental or a past conscious state, so long that Bergson's distinction between states and objects no longer seems to hold. Recall: states have contingency for him and objects necessity.

For Bergson this necessity underlies our metaphysical assumptions. It is he says, as it were, hypostatized. And so it should be in our post-Einsteinian chronogeodetermined 'block' universe, but this is not for us the case. Contingency underlies our metaphysical assumptions.

For us, as for Meillassoux, a radical indeterminism enters the picture. At least, it enters the world of objects, and not so much that of states—at least those, like memories, we can observe. Neither radical indeterminacy nor contingency are what they used to be.

Our memories just don't have the stochastic movement Bergson accords to them. We replay them endlessly—and how are we able to do that?—to find out their secrets, as if there is another world beyond them to which they refer. And isn't this the case with Meillassoux's radical contingency? that it doesn't refer to our own world and that of our experience but to one beyond this one?

Contingency has been, as it were, hypostatized, but only as it refers to a cinematic ontology, in which it is captured.

The shot has captured contingency. We are not the sum total of a contingent number of facts. We are the necessary combination of scenes and images which have been highly edited.

REVERSABILITY

Determinism means what can be repeated precisely the same way even if it is radically contingent. Our mental states are cinematic inasmuch as consciousness may be the narrator but the unconscious (which the Surrealists were aware of) is the editor. Where I am heading is not to reverse us, take us back to pre-cinematic certainties of the world around us and of our experience in it, when our inner states had greater freedom. I think however a way back is hinted at, which takes us forward, in the following: Stanley Kubrick interviewed by Michel Ciment, 1971—

I think modern art's almost total pre-occupation with subjectivism has led to anarchy and sterility in the arts. The notion that reality exists only in the artist's mind, and that the thing which simpler souls had for so long believed to be reality is only an illusion, was initially an invigorating force, but it eventually led to a lot of highly original, very personal and extremely uninteresting work. In Cocteau's film Orpheé, the poet asks what he should do. 'Astonish me,' he is told. Very little of modern art does that—certainly not in the sense that a great work of art can make you wonder how its creation was accomplished by a mere mortal. Be that as it may, films, unfortunately, don't have this problem at all. From the start, they have played it as safe as possible, and no one can blame the generally dull state of the movies on too much originality and subjectivism.

–Stanley Kubrick, source (full interview here) (and further to here)

Finally, I'd like to draw your attention to the results of giving therapy to different models of artificial intelligence. I believe current epistemological models to have more bearing on the diagnoses, across the board, in different degrees, of psychopathology, than ontological, with the one exception of a cinematic ontology. LLMs seem to me to be great examples of the cinematic description of mental states. We have after all created them in our image.

Please follow the link: "When AI Takes the Couch: Psychometric Jailbreaks Reveal Internal Conflict in Frontier Models,"Afshin Khadangi, Hanna Marxen, Amir Sartipi, Igor Tchappi and Gilbert Fridgen, University of Luxembourg, 2 December 2025.

*In the time crystal, cinema reflects on the cinematic perception of time, which, defining the shot, is that of contingent motion.