introducing ① Enduring Dreams: a note on cinematic time (sections 1 – 9)

Digest is currently serialising the work, Bergson, Deleuze & Cinema, from the first part, entitled "Enduring Dreams: a note on cinematic time".

Sections 1-9 have appeared here so far, they are compiled as ① for recent subscribers to outside light to catch up with the story so far ...

CINEMATIC TIME

In their introduction to Henri Bergson: Key Writings, Bloomsbury 2021, John Ó Maoilearca and Keith Ansell Pearson offer in answer to Bergson’s solution to Zeno’s paradoxes Bertrand Russell’s own:

A cinematograph in which there are an infinite number of films, and in which there is never a next film because an infinite number come [sic] between any two, will perfectly represent a continuous motion. Wherein, then, lies the force of Zeno’s argument?

Why does Russell use this image? Why does he choose the image of a cinematograph? An early piece of film gear, the cinematograph combined the functions of both projector and camera. By the time Russell is writing cinematographs had been in commercial use for 27 years.

Why did he not revert to Zeno’s own examples or talk about an endless succession of clouds? Why not choose a natural phenomenon? or is it to Russell’s point to use this one? Is there a reason to refer to cinema in this context?

I’ll come back to this because the point of this note lies in the contrast between cinematic time and natural time. Cinematic time is more readily understood than natural time and this too speaks to my purpose. By cinematic time I mean the kind of time that cinema, film and moving images in general occupy. Natural time is then the time taken by natural processes, organic and inorganic, whether they are themselves living or inanimate, the time they animate.

I think Russell exemplary for the contrast I am making not because he formulates a concept of cinematic time but because of the contrast between his views on time and Bergson’s. Bergson’s explanation of time is that of a duration. In duration he is dealing with the time properties of natural phenomena. For me duration is then exemplary of natural time.

BERGSON’S FALLING STAR

The Russell quote Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson use in the introduction to their editorial choice of Bergson’s key writings is from Our Knowledge of the External World on “The Theory of continuity,” Lecture V, 1922. They cite Russell because of his lasting influence on Bergson’s subsequent reputation. Russell contributed to the fall of Bergson’s star, a star that at the time had burned more brightly than any philosopher’s.

1922, the year Russell’s work was published, was also the year of Bergson’s debate on April 6 in Paris with Albert Einstein. The echoes of this event are still I would argue being heard if not felt or recognised in our contemporary philosophy, including in the philosophy of science. Einstein and Bergson debated the nature of time. It is said that Einstein won.

Although not widely discussed, his win contributes to Einstein’s rise and Bergson’s fall, the one eclipsing and outdoing the other in popularity. It is even forgotten that Bergson, particularly among women, enjoyed such mass appeal. This is another mark, in Russell's view, against him and his philosophy.

Russell vilified Bergson in plainly sexist language. Where Einstein beat Bergson in popular culture, Russell is largely responsible for his sinking below the surface of the philosophical mainstream. We might even date the divide between Analytic, anglophone philosophy and so-called Continental philosophy to Bergson dropping from sight.

The context for the waning of Bergson’s reputation is strongly linked to what he himself considered his principal philosophical insight. This was into the nature of time. The insight into the natural duration of time is behind all his later work.

DURATION OR NATURAL TIME

Bergson realised that in science’s understanding time needn’t pass. For science there is no endurance. There is the passage between states but in themselves these do not endure.

Science does not measure the time internal to their endurance. Rather states are measured at each end, from end to end, from startpoint to endpoint and from any point inbetween that can then serve as start or end. In the beginning a state, whether it issue out of a preceding state or not, is not and then is. The time internal, the time endured, Bergson called duration.

Science and Einstein’s spacetime of relativity rely on simultaneities. A state in its is-ness is related to another in its. This is true for the states of measuring devices. It is therefore true for the clocks of the two clocks thought experiment.

Bergson argued that relativity was not a temporal phenomenon. It had nothing to do with time. It brought into relation simultaneous states, the time-reading of the two clocks.

One clock had been travelling and one not. When compared, the one that had been travelling ought to lag behind the other. According to Einstein time passed more slowly for the moving clock and the faster it moved the greater the lag. For Bergson, these relative times were not being measured, the two states of the devices were.

The time internal to the travelling clock was not being compared to the internal time of the one holding its location. A clock does not in Bergson’s sense measure the time passing. It uses a spatial analogue for it.

Here time is not passing but, since it goes by the point it is recorded, still and present. Its relation then to Bergson’s idea of the real time of duration is given by convention and that convention rests on a spatial metaphor. A durational measurement of time is impossible to make by fixed quantity. It is a quality, an intensity, that can only be intuited by a feeling and from its experience in duration.

Time as duration is inaccessible to ratiocination. That it must be felt does not make time an exclusive quality of consciousness. It does however render it irrational and this is Russell’s finding with regard to Bergson’s philosophy, of it being irrational, intuitive, therefore nonanalytical and effeminate. Moreover, for Russell, Bergson is guilty of making philosophy over in the image of his own irrationalist, intuitivist, anti-analytical and feminising impulses. Worse, he is unapologetic in doing so.

HISTORICAL TIME AND THE CONTEST BETWEEN CINEMATIC TIME AND SCIENTIFIC TIME

Reading Bergson is difficult because of a set of metaphors wholly other to those found naturally in language, in fact allowing them to relinquish primacy and sink into the background. This is the same background of historical time and historical context that Bergson is seen to sink into, making it less and less likely for Bergson, in its passage, to have anything useful, effectual or relevant to say to us, his readers today. The set of metaphors displacing the ones identified by Bergson as standing in the way of thinking durationally coincide with the historical time he was writing. They come from cinema.

Before dealing with what is meant by saying that the predominant means used to think about time take their metaphors from cinema it’s important to enquire further about the contrast between scientific measurable time and time as duration. Is there really a contest between the two? Isn’t Russell right in thinking Bergson’s notion of time to be too diffuse to be useful, too intangible and, if not feminine, subjective?

Duration might have some psychological validity but no scientific validity. It is at best a psychologism, a matter of subjectivity and, ultimately, opinion or point of view. So there is no contest, is there? As Einstein is alleged to have said when Bergson presented his counterargument to contrast with Einstein’s views on time, “The time of the philosophers does not exist.”

For duration to be a contrasting view of time it has to stand up on its own. Astrophysics professor, Adam Frank, in a nice article written from his reading of Jimena Canales book about Einstein and Bergson’s 1922 meeting, asks in its title, “Was Einstein Wrong?” This is to raise to the level of contest what has not yet been determined to be in Bergson’s duration a contrasting view of time, but Frank also raises the question of whether Einstein’s spacetime stands up on its own.

Frank claims, after Canales in her book The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate That Changed Our Understanding of Time, 2016, that Bergson was not presenting an argument to counter the notion of spacetime. He did not want or mean to counter the physics but the metaphysics. Without certain metaphysical assumptions spacetime is not a concept that stands up on its own. Therefore it is at the level of metaphysics that the notion of duration becomes contrastive and worth putting up against, pitting against spacetime.

Spacetime, writes Frank, depends on the metaphysical assumption of chrono-geo-determinism. This is a view of the block universe. In the block universe everything that can happen, has happened and will happen exists. Each event exists in its multidimensionality as actual and discrete.

A divisible part of its multiplicity, what happens, has and will happen is chronologically and spatially (geometrically) determined. So it is predetermined but it makes no sense to say so since the temporal distinctions of before, pre- and after cease to matter. Time as succession, however it may be physically necessary to bodies in motion, is no longer metaphysically supported in such a view.

Bergson suggested that it was not only habits of thought that stood in the way of our thinking durationally but language as well. Spatial metaphors for time were built into language. My own finding is that the greatest obstacle to understanding Bergson is not language and the spatial metaphors inherent to it.

VIRTUAL MULTIPLICITY

Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson in their introduction distinguish between this kind of multiplicity, where everything possible is actual and exists, of which temporal succession is no longer a necessary part, and what Bergson calls a virtual multiplicity. A virtual multiplicity is not composed of discrete and divisible and therefore measurable and countable events but of states of duration. These are diffuse and, from being purely virtual, they come into being.

They are not divisible except qualitatively or intensively, by relative differences of intensity. These states are not discrete, they interpenetrate. They are ever in process.

Against the absence of necessary temporal succession in the first type of multiplicity, of the multiverse or block universe, the second type, of virtual multiplicity, presents the temporal succession of different qualities, intensities, states in process, that come into being and pass away. This overall process Bergson calls duration, pure duration or simply time, but the absence of necessity of succession in spacetime does not mean its necessary absence. This is what Russell is trying to show in his handling of Zeno’s paradox, that the discontinuity of discrete states of things does not exclude their continuity in a kind of time.

How does science show time? How does mathematics show the continuity of succeeding states, from one to the next? How is change conceived of? It is not common here to talk about chronogeodeterminism as Adam Frank does.

The tendency, even in quantum field theory as it has developed from complexity and chaos theory, is to show, for example in paying close attention to and taking measurement of initial conditions, that change occurs according to laws. These laws are, broadly considered, deterministic. Were they not and did they not remain so there would be little room for them in science. They would not be supported by its epistemology, that is according to its (metaphysical) assumptions of what constitutes scientific discourse and knowledge.

TIME AS SUCCESSION: DURATION

Since duration frees succession from predetermination, since duration saves time, so to speak, from the determinism where saying pre-, before and after, actually makes no sense, there does then seem to be something worth contesting. Bergson’s duration shows succession. It shows time to be of the order of continuous succession.

For the time of states that interpenetrate, that are always in the process of coming into being, succession is not only evident but necessary. The order of time has to be one of before and after. Time as duration, for the reason it is of a virtual multiplicity and is ever coming into being and passing away, belongs to a continuity that cannot be predetermined and is nondeterministic. It is a time adequate to both freedom of action and indeterminacy.

Does this order of time differ from the common naturalist view of time being a succession in continuity and at once able to be decomposed into discontinuous and actual states? Does it differ from the view of temporal succession able to be divided without altering its underlying nature of being continuous? This is the source of Zeno’s paradoxes relating to bodies in motion. It is also the source of Russell’s paradox of the cinematograph, where I believe Russell articulates a naturalism belonging to cinematic time.

ZENO’S PARADOX: MOVEMENT AND THE NATURALIST VIEW

The fact of this articulation points to another source in natural language. Language, in particular written language, gives the impression of there being a continuity underlying discontinuous discrete states of things. The letters don’t make sense without it. Then where does this sense, the sense of continuous movement come from?

Sense has the continuous movement of making sense that time has too. It is there in what may be called natural time. This naturalist view is what Zeno set out to challenge and inasmuch as he gives the sense there is a paradox here he succeeded.

All is movement according to this naturalism. All however is not in movement, otherwise there would be nothing solid to grab hold of, but, whether the movement is of sense or of water or of the particles it carries along, for this view, for the temporal continuity supposed to underlie stable appearances, movement is prescriptive. It is the way time is pegged to movement that produces paradox.

The all, of all is movement, can be divided at any point. Zeno supposes the realisation of this potential. Being broken at every point it can be brings about either the cessation or the breaking down into parts and more parts of movement and from these parts the whole can no longer be accomplished.

Time however does not cease its achievement. It carries on regardless as if movement itself were separable from time. While for science time is a function of points articulated in space, for the naturalist view these points articulate time. Stillness rules time for the scientific view, leading to the immovable chronogeodeterminism of the block universe. Movement rules time for the naturalist view, leading to the paradox of the points along it being time’s stopping points.

Bergson’s answer to Zeno’s challenge is similar to his answer to science. He answers science’s division of time into simultaneities by saying that no such division can occur without a change in what is taking place in time, without qualitative change. He answers Zeno by saying that movement is not an accumulation of movements and so cannot be composed and decomposed as if it were.

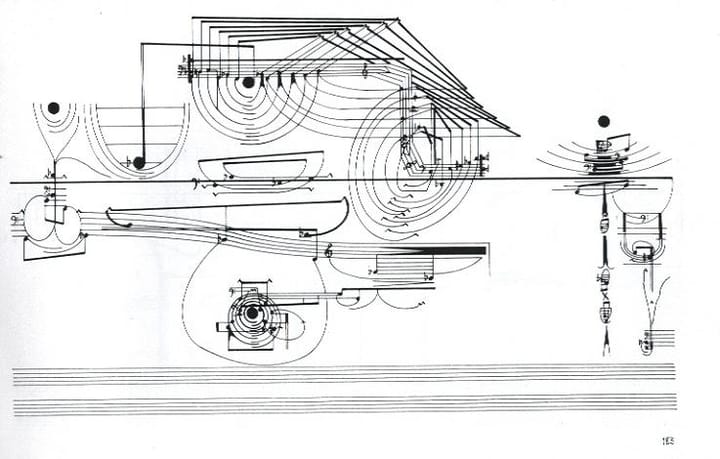

The flow of his writing gives the same sense as he ascribes to a melody in music. Were it to pause and draw out any one note there would be a qualitative change. This is so for the movement of a written thought, for a melody and for the movement of physical bodies. Movement happens at a single stroke. It is indivisible according to Bergson.

Divided, its quality changes. Achilles need only walk to prove it. What Zeno shows in his paradox, since the change in the quality of Achilles’ steps, is a race between two tortoises.

Bergson’s answer to Zeno’s challenge to the view of time being articulated by movement and therefore composed of the series of points moved through is to point back to the time that movement takes, stating that time is neither an accumulation of nor decomposable into points or discrete states. To subtract one state that is moved through changes the nature of the whole movement. It is not with quantities of time that Bergson answers Zeno but with its quality, the overall step of Achilles being unequal in its quality for the time it takes to that of the tortoise.

Russell however does not accept the terms on which either Zeno’s challenge to the naturalist view of time or Bergson’s answer to that challenge rests. Between 1922 and Bergson forming his ideas around time and his answer to Zeno a new analogue for time has come into being. It is in Russell’s answer to Zeno, the cinematograph and cinematic time.

RUSSELL’S ANSWER TO ZENO: THE CINEMATOGRAPH

What is significant for Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson, is that Russell answers Zeno’s paradox with another paradox. The continuous motion of time is upheld by the continuity of an infinitely unspooling number of films. There is never any next film but an unbroken stream.

The films are not, as in Bergson’s example of a melody, indivisible. They are measurable, tangible. They may be stopped at any point without there being qualitative change. Russell’s view shows a naturalism to his cinematic example, that of a cinematic analogue for time. As Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson put it, without really asking why or stating what it is, Russell answers Zeno with another paradox.

They instead charge Russell with dogmatism in arrogating to his own view a validity that is both logical and mathematical, and that does away with the need, as Einstein also says, for Bergson’s philosophical time, but what is convincing in Russell is not the logic, rationalism, mathematical and scientific validity or the truth of his view of time. It is rather in the nature of his example. It has to do with the cinematographic image.

We are more familiar with streaming media than film. We might update Russell’s image for the digital image. Its internal logic would still hold. In the stream of images there need not be any next image but between any two there can come an infinite number. It might then be asked, what is the paradox that Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson find in Russell?

They insist that Russell’s mathematical time is not like that of the naturalist view pegged to movement. It can’t be decomposed and recomposed by infinitesimal periods of time or distances in space. It has to do with continuous series where there is no next. Its failure, for Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson, is that of being an actual multiplicity and not a virtual multiplicity. The states it describes have to be actual and existing, not virtual and coming into being as with Bergson.

Looking at it from the outside and taking Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson at their word, the paradox for me resides in there being as Russell states it no next film. It’s worth noting at this point that in 1922 cinema programmes comprised successive films. Each required the loading of new reels. A feature, like The Toll of the Sea, 1922, running at 54 minutes, took up 5 reels, but typically in the 1920s a reel was 15 minutes long and held one film.

The paradox therefore is that in Russell’s “infinite number of films” there is always a next film. If Russell had attended one of over 1000 cinemas, as there were by 1914 in London, to see a particular film on the programme, he might have been very disappointed. If he had stayed his whole life, he still may have left without seeing it. However what Russell is attempting to assert, despite the paradox of each new film being the next one and yet there being no film consecutive to another, is the continuity of the series. Its continuity allows, without breaking the mathematical series, for the intercalation between any two of an infinite number of films.

That the programme plays without a break is the assurance of the mathematical series, but this, say Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson, bears no necessary relation to the actual world. Neither, says Russell, need it have any relation to actuality nor to time for it to be preferred and asserted over Bergson’s philosophical time. Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson call Russell out then on the dogmatism of the assertion of mathematical time in place of philosophical time.

What they don’t do, as it is probably beyond the scope of an introduction to a selection of Bergson’s writing, is investigate Russell’s claim for mathematical time in view of the nature of cinema and of cinematic time. My view is that Russell’s image of time, however paradoxical or dogmatic in its statement, is naturalistic. It engages a cinematic naturalism. More than this, the image given of time by Bergson’s writing, from Time and Free Will (in French, Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience, 1889) on, cannot be understood without difficulty after the advent of the image of time I have been calling cinematic.

THE PREVAILING IMAGE OF TIME

Russell is the beneficiary of the advent of the cinematic image of time, since it is his view of mathematical time that historically has prevailed, in science and in large measure for philosophy. This image has created more problems than it has solved for our understanding of time. These problems are being played out today in particular by quantum theory, quantum field theory and in the attempt at a grand unifying theory.

Bergson’s target was a mechanistic view of life but, since the capture in the moving image of a particular kind of time by mechanical and technical means, the target shifts. It has shifted to the relation between cinematic time that captures the moment and the playing out of life. I would say then that these scientific problems ramify across our understanding and, since cinematic time captures the moment of life by capturing its movement, I would say that they radiate out over the whole of human activity. This is part of the reason for this note.

That these problems are not held exclusively by either science or philosophy, since I am expert in neither, is the whole reason. I’m a thinker not so much of thought, of philosophy, as, being on the side of cinema, a thinker of practice. Bergson’s appeal is that of allowing me and I hope you, through this note, to get under the hood of what is happening in the relation of life as it rolls out and the moving image that winds it up in the kind of continuous and unbroken succession Russell imagines belonging to the cinematograph.

The fact is he imagines it. On the side of cinema there arises a wholly different picture and image of time and, on the face of it, it looks like Russell’s paradox, of there never being a next film through the interposition of any number between this and any other one but yet of there always really being a next film, unlike Zeno’s paradoxes, is not intended to pose a challenge to the naturalistic view of time, whether cinematic and to do with moving images or, as for Zeno, to do with moving bodies. It looks like Russell espouses the view he makes a paradox out of, as if he does not recognise that he is making a paradox.

Having come this far and in light of what Ó Maoilearca and Ansell Pearson say it might be asked whether Russell’s dogmatic assertion of a view of time in place of the philosophical time Einstein said to Bergson does not exist is the mathematical or the cinematic one. This brings this note back to what I asked at the beginning, why does Russell use the cinematograph as his example?

Is there not an example that better fits, that is closer to his only option for philosophical time? Why not talk about the infinite number of points that intervene between any two points on a line so that there is never a next point? Why not talk about an endless succession of clouds in the unbroken continuity of which there is no next cloud? or of crickets or birds in whose song there can be said never to be a next note, a next stridulation? Wouldn’t any natural phenomenon serve the purpose of showing the sense of continuity, of the compact continuity against which he proposes that Bergson’s duration does not make sense?

Even in his example, of films, there would seem to be one closer to the temporal model of mathematical time. Why not say that between two shots any number might be inserted, or between two frames there might be any number of frames? so that a movement would never be completed, a sequence or scene could never end? There would still be no next shot, no next, simply the continuity that he is trying to draw our attention to but as I’ve said, I think the reason for Russell’s choice of image resides in the transformation of the nature of temporal experience effected by the advent of cinema and of the cinematograph. However there is one more point to make before getting there.