② motor-diagramme is the movement of consciousness

Let me say first up that what I am doing is reading Bergson's Matter and Memory, which appeared in French 4 years before the turn of the 19th century in 1896 and in English translation, translated by Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer, 15 years later, in 1911; the dates' sole significance being that this is very long ago, long enough for this book to be presumed of negligible significance. To us that is. Yet on the back we can read Walter Benjamin, Gilles Deleuze and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, each with his own take on Bergson's book: for Benjamin, its attempt to lay hold of 'true' experience in contrast, here showing his Frankfurt School leaning, to the standardised, denatured life of the civilized masses. That we can recognise our own age in terms of this description is beyond doubt (also pointing to the influence of the originally Marxist-inspired Frankfurt School's Critical Theory, in critique of capitalism, which perpetrates standardisation, denaturing and mass-ification). For Deleuze, true to his philosophical frame, Bergson's book is not critical but diagnostic, and responds to what is critical or what has reached the point of crisis, with the time-image. What's that? I'm still trying to figure it out. I know that the work in which Deleuze addresses himself to it is that on cinema, the books Cinema 1 and Cinema 2. I also know part of the reason, if not the whole reason, that Bergson, promoter of intuition, is viewed, if not with suspicion as a mystic, then, the inventor of the concept of duration, as having nothing to say to readers 20 or 120 years after he was writing, is time. Our concept of it has moved on, which is also to say our image of it, which relates to the impetus behind my reading Bergson now, cinema, which is of course the art of the moving image. Merleau-Ponty recommends, perhaps pointing to the future we inhabit in its post-humanity, a potential, like so many post-s presumed rather than actualised (my favourite joke about post-colonialism is that at its mention you might readily reply, What? Have they left?), Matter and Memory for rediscovering a 'pre-human' sense of the world. From his own philosophical framework, Merleau-Ponty is pleased to find in Bergson as in noone before a description of the perceived world's brute being, which we today can call its nature.

I am reading Bergson, carefully, because when I met him, met with his work, I found it difficult, I couldn't understand it. Unlike with Deleuze, who also arouses suspicions among straight-thinkers, those who put lucidity of thought and clarity of expression before difficulty, suspicious of it for dressing up what could be put more simply, who are all, as Mark Anthony says, reasonable (usually) men, I couldn't say what the difficulty was. All I could see, despite its lucidity, despite its clarity, was that there was more to it than could be seen and an obstruction to it being seen. This obstruction I have since identified as the advent of cinema—which is why I turn from Bergson to Deleuze, and turn again, not because he throws any light on what is difficult about Bergson but because he offers a further complication: (also a clue) since for Deleuze, Bergson, thinker of the time-image, is the thinker of cinema.

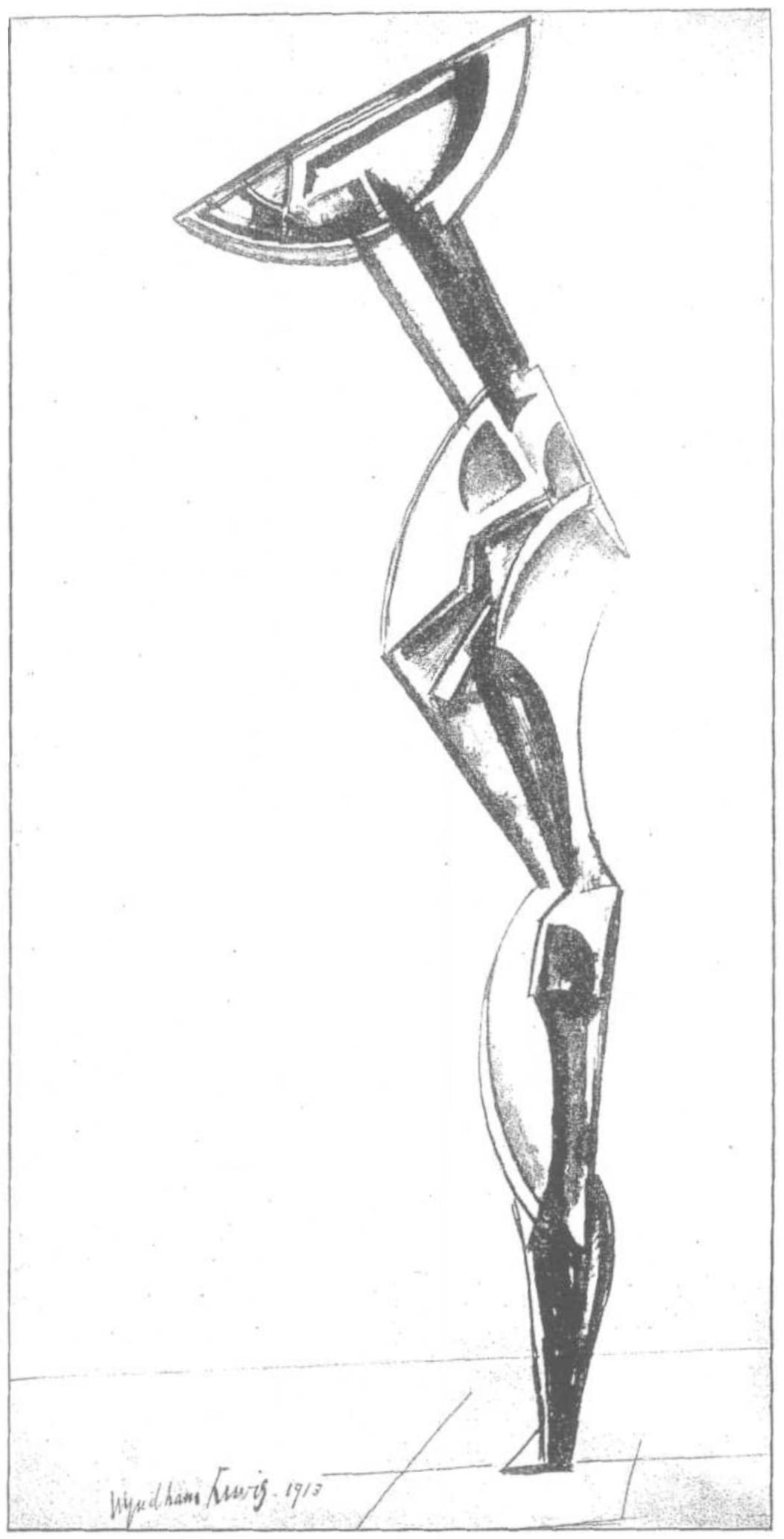

You can see how this thread of thinking loops back on itself to form a knot. For the Vorticist, Wyndham Lewis, a knot was the very figure of energy. It's not however very friendly to readers who can readily tell the writer who ties them up in them to get knotted.

All of which doesn't excuse but explains the stepping-stones I am laying out now, which although numbered consecutively are not in succession. Each is to be regarded if you would be so kind as to regard them at all as an instance in isolation, an island. And on this island called ② if you feel there's something to see that cannot be seen or something to say I have not said, because I am here with you, ask and I will try to answer you as soon and as well as I can, let me know.

Matter and Memory is cited, including page numbers, for ease of reference, from here. For further links, including some interesting material on Wyndham Lewis, here.

Why does consciousness elude neuroscience?

- because of a number of images which insert themselves into its motor-diagramme.

The pages in Matter and Memory I will be looking at are:

p. 47, where Bergson writes "In the particular case we are considering, the object is an interlocutor whose ideas develop within his consciousness into auditory representations which are then materialized into uttered words." The context then is of language and, a subject at present near to me, language acquisition.

From there we leap several pages to:

p. 49 in the online edition, where ..."we have said that we start from the idea, and that we develop it into auditory memory-images capable of inserting themselves in the motor diagram"... (I will be giving preference to "motor-diagramme" in the following.) And reading through over the next pages, in which there is a decisive move from the motor-diagramme of an interlocutor developing ideas which develop within his (or her) consciousness, as above, to a diagramme with psychology as its object—psychology I believe we can elide with neuroscience—we come to:

p. 51: ..."images can never be anything but things, and thought is a movement." Bergson's issue is with what he calls that invincible tendency of the sciences ..."which impels us to think on all occasions of things rather than of movements." (49 in the online edition) From our familiarity with this notion, of sciences having to freeze and isolate objects of study, not to say silence them, we might be inclined to accept this statement without question, so that makes a good place to start, to start questioning our own inclination, against a tendency, an invincible one, in Bergson's mind.

The first question we can raise against the thing-ness of scientific objects is that we have the record of moving things to support, on one side, the idea that everything is in movement, and on the other, that thought is like this too. What distinguishes it from moving things, and what perhaps does not distinguish it enough for us to separate thought from things that move, is that the moving things of thought are less substantial. In terms of classical philosophy they lack extension, and therefore materiality. They are immaterial things and, it is less an invincible tendency of our own times that things unlike thought, even when the objects of scientific study, don't move than that thought is united with our recording of moving things in our minds as moving images. Cinema I would say here makes a difference.

When we think of recording speech processes we think immediately of what happens in the brain and subsequently of the movements which occur in the brain that the different methods of scanning it can record. We can stop here a second to observe that the technology used to scan brains is of quite recent development and that progress in high-definition and real-time scanning is how we tend to measure progress in this field in general. However, in commercial use, the method of recording moving images goes back to a year before Matter and Memory was published in France. The spread of its commercial use for entertainment was explosive. If this were the case with MRIs theirs would have been too.

Over the interval when I had given myself the task of finishing the thought, this 'stepping-stone' or 'island,' elicited from reading Bergson, my phone's news algorithm . . . just then, as if for proof of the motor-diagramme, the fire alarm went off, a message was broadcast not to use lifts, I found the stairs and came out the service entry to the rear of the Ascott Rafal, where workmen were, despite the piercing siren, still going in and out, around to the lobby, where I asked if it was a drill, Yes, sir, you have received a message, on paper, about it. I didn't, I ran down the six flights of stairs, the doorman put his hand across his heart in apology. Safe to go up? The siren's stopped? Yes, sir. I had thought it odd that I met noone on the way down. . . played (I can't think of an adequate verb to use for how an algorithm not only chooses but foists its choice upon one) this article: "Wired for Words: Understanding Language and the Brain: Neuroscience has finally cracked the code on how language works in the brain." From Psychology Today, a commercial US website, by Gregory Hickok, PhD. the article claims for the field in which Bergson is staging his philosophical intervention that from the 1800s, when he was writing, to 1998, there hadn't been much progress, but since, it has been "astounding." This is thanks to the core insight of language as a "species" of sensorimotor processing (scare quotes in the original).

What Hickok, in the book, Wired for Words (MIT: 2025), the article is drawn from, calls the "new integrated framework" of LSM, the Linguistic-Sensory Model, is allegedly still as provocative as when Bergson first proposed it:

The most provocative claim of the LSM is that language processing shares the same fundamental neural architecture as non-linguistic sensorimotor systems—like reaching for a coffee cup or tracking a moving object with your eyes. This doesn't mean language is "just" movement or that decades of linguistic research are invalid. Rather, it suggests an evolutionary relationship: the two types of systems are homologous.

LSM apparently, however, still falls foul of the problem Bergson identifies, which is where he goes meta with his characterisation of the motor-diagramme that he identifies with the movements Hickok maintains wire us for words. (Already in this speech, this way of speaking, we can hear echo, down a hundred years, that invincible tendency of Bergson's, to render the brain, along with its language-processing centres, in their distribution, a thing.) To explain how the meta-diagramme of scientific discovery works, we need to see how it works motorically, that is, these movements being the ones recorded from brain scans of which the LSM currently provides the best explanation, in terms of movement.

Bergson asks what happens when we listen to the words of an interlocutor, of what are we conscious? (49) Do we wait for the speech-impressions to produce for us answering auditory images? these, in the meantime, recalling for us images and associations making such sounds, the specific sounds we perceive, recognisable and giving them meaning? Or, rather, don't we feel ourselves taking on a kind of attitude, which is at its extremes felt physically, as either being taken on by our bodies, with at the one extreme, joy and acceptance or at the other, with feelings of physical repugnance towards what we don't want to take into our bodies, is rejected by us?

Bergson talks of a physical disposition being required, that wires us for words, to understand language. He says that we acquire language through making and repeating the movements of the words, which movements occur in the brain and central nervous system, which are in fact the wires. They don't connect the auditory cortex to the motor cortex, by way of Wernicke's area and Broca's, in the hierarchies of Hickok's diagramme (here), rather they connect ideas, which is where they start and what they start with in the object of our interlocutor, to ideas, in the listening subject of ourselves.

The motor-diagramme, of Bergson's description, follows through all its windings the curve of our interlocutor's thought to show our thought the road. The auditory images are its road-signs and the associations of our recall both pay attention to them as they flow into the movement, says Bergson, an empty vessel, "which determines, by its form, the form which the fluid mass, rushing into it, already tends to take." (49) The process is immanent. There are no hierarchies involved, as Bergson dispenses with the notion hierarchies exist in languages, between those having many words with many shades and nuances of meaning, and those with few. Every language, he says, whether there are many or are few, contains what act simply as guides for thought. And if many, that we can feel a sense of physical restraint, attests, as is attested to also by the LSM, to the motor-diagramme being more than mere analogy.

As immanent to being formed, and to becoming the changes it is, I would say the motor-diagramme of language is a perception of the body, a centre of action, which, as an active principle, down to the cellular level of biology, starts with movement. This movement enables the acquisition of language together with the enactment of language. Addressing the localisation in the brain of processes associated with language Bergson considers how the diagramme showing the paths of communication, and their order, taken by various parts of the brain became at the time he was writing increasingly complicated. The reason he gives is the thing-ness science attributes to movement, that of the continuous movements of locution and audition, being broken down, localised in the brain, from which the attempt is made to reconstruct the overall movement. He does not draw attention, in addition to the motor-diagramme, to having introduced a second diagramme, an historical theoretical one, which seeks to explain it. Both provide diagrammes of consciousness, the one in biological-cellular movement of the body in its physical disposition, the other in the historically acquired functions of scientific perception.

The motor-diagramme describes movements of biological perception, which happen to be linguistic; the latter 'diagramme,' which for operating at a meta level is no less motor-ic, overlays the former with its own symbolic and cultural understandings, from the perspective of a perception that derives from those symbolic and cultural understandings. It only happens to be scientific and is still a movement, historically formed and determining by its form, that which the fluid mass, rushing into it, already tends to take. This is not to relativise its explanatory value but to draw out an account which is latent in Bergson of the two diagrammes that going beyond mere analogy speaks to the nature of the diagramme: it is nonhiearchical, neither is one subordinate to the other, nor is the theoretical diagramme of scientific perception secondary to the practical motor-diagramme of biological perception.

Movement as such can be said to include its own diagramme, no less the movement of consciousness, Bergson gives the example of our becoming conscious of a physical attitude that prepares the way for meaningful linguistic exchange and which can today be mapped in the movements of the brain, than the movement of the moving image on our screens. To come back to my question, why does consciousness then elude neuroscience? Although the movement of the motor-diagramme, which here can figure for the biological form of consciousness, is continuous, because it has a distinct duration—as life does, as consciousness and, no matter how prolonged, any movement do—it is, forms or forms in a continous interval, into which are inserted images, both voluntarily, by, for example, recall, and involuntarily, for example, by habit.

Once the movement of consciousness is itself elided with the moving images of cinema, so that there is no distinction between them, the one is occluded by the other. Cinema becomes the motor-diagramme of thought; and thought, the motor-diagramme of cinema. The images of consciousness that are inserted into the diagramme of neuroscience are cinematic.

To say it in this way is leading. It leaves unsaid that in every perception of the body, that is, in every perception that is ours, there is a biological motor-diagrammatic element. We have a disposition towards certain tastes, sounds, images and ideas that shows itself in movements, which brain-scans can pick up, however what they cannot pick up is what those tastes, sounds, images and ideas are, except as the probabilities from which AI is good at parsing viable options.

The technology being publicised as 'mind-captioning' (see article) is exemplary in this regard, with its advantages and drawbacks, allowing people locked-in to communicate, with 40% accuracy. Of course, it struck me that video footage was used to test the accuracy of captions offered by AI to the nascent movements scanned from experimental subjects' minds: not the more complex, because multi-sensory, physical dispositions of the motor-diagramme elicited by lived scenarios but that limited to sight and sound.

Not only does what I have said leave unsaid the part played in all human perception by biological perception, the part Merleau-Ponty might say is played by the 'flesh.' I have not gone into how our limitation to the two perceptual attributes of thought and extension plays out in our current era, in contrast to the infinite attributes that are nature's. My view as I write this is that the way to one is through the other.

. . .