⊖no windows

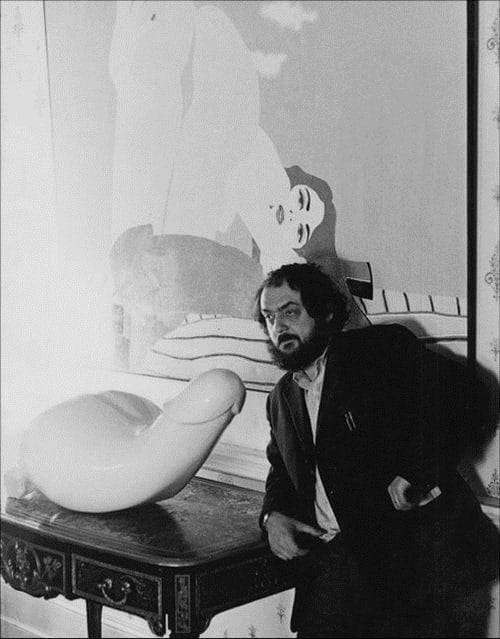

see also the arrows works by Gordon Matta-Clark, shown here, which don't resemble those of another artist known for arrows, for example,

Tàpies, whose textures are rough, Whiteread, who fills a lived volume, Matta-Clark, whose most well-known work is severed and cut, something it is said to do with his formative years. . .

The danger with starting on an intellectual digest journalling the movements of thought from day to day is that

- as if you are writing your dreams you start to dream in order to write the dreams down, so you rush to fill in the gap and perform the thought before it comes and you start to think for the writing

- the movement comes to take the place of what moves it

- a third danger is from thinking thinking is a productive process, so locating what moves it, . . . usually in the past, in the desires and drives said to derive from the formative years

which is more or less true of all three of these artists; but I prefer the anecdote Laurie Anderson tells in Heart of a Dog, the 2015 film she made, not the short story of the same name by Michail Bulgakov from 1925, which starts in English translation

Oo-oo-oo-woo-woo-woo-hoo-oo! Look at me, look, I'm dying.

about Matta-Clark. When he was dying in the hospital, two Buddhist priests were stationed at either side of the bed, near his head. Buddhists believe that hearing is the last of the senses to leave us, when it is required priests are present to guide the dying onto the next life. The priests who had been still and silent until that point began to shout,

Robert!

You're dying!

You're dying, Robert!

they shouted into his ears:

Go towards the light!

No. . . not the first one!

. . . the second one,

the one that's further away!

A further danger is, adding unnecessary detours and pointless details, putting off what needs to be said, either because it hasn't been or is resisting being formed. And as to why it is resistant you will have to ask the psychologists, yet no amount of pressure may yield it. In fact, pressure simply increases pressure from the other side, or equalises it, so it becomes a matter of indirection to . . . get to the point, which brings us back around to the detour, the real danger of which is that it is seen as an end in itself, perhaps because it produces some good writing. However, above all, Levrero, the writer of the unnecessary, above all, is the best judge of what constitutes good writing: he seems to know, even when he is doing his calligraphic exercises in Empty Words, or *mpty *ords, as it is titled in English. And this stands to reason, at least to the subsidiary point, or supporting point I am making here: when I say what needs to be said resists and we need to try indirection, then, there is the unnecessary; but do we forget what needs to be said, what presses on us to be said? No. This is exactly Levrero's good. I mean you can see his enjoyment, even when complaining of certain domestic circumstances which keep him from writing, of, and also his acknowledgement of, unnecessary writing. What does he say about it? That it gives the unconscious which he trusts, to the trust of which he is committed, because his unconscious, not some general warp in the weft of things, the greatest amount of freedom. I am here pre-empting something I want to be getting on with saying in ②, the third Digest entry, the one after, marked with ⊖, this one, to indicate that it is a non-starter. . . And this also needs to be said before moving on: it is not to reach ② that I am writing ⊖; it is in order to that one initiate the series: ① ② ③, or even ①⊖②, or this, which can fall after any of the others, beautiful symbol 𝄐

The danger of succession the TV show demonstrated. What is it about it? . . . I would risk suggesting in the case I am dealing with at present that matters of succession retroactively produce the resistance I have named above of things to declare themselves: I am not being playful but dealing with this exact problem:

the problem of there not being a problem

a problem is a window and it is, as the Alexandrian poet put it in the final lines of his poem "Windows," exactly another tyranny it, and I use the word projectively, proves:

perhaps it's a good thing a window doesn't open

perhaps the light will prove another tyranny

who knows what new thing it will expose.

–Cavafy (29 April 1863–29 April 1933)

. . .

No problem is a problem for succession because there is nothing to inherit.

Briefly to elucidate: the hackneyed image of piling abstraction on abstraction. With no windows the issue is not no impulsion, no drive to, for example, write, but that the drive is up ahead and, for one reason or another, inaccessible. It is that nothing necessary, or in Levrero's case transcendental (The Luminous Novel, 2005, takes 100s of pages of unnecessary writing to get to the luminous, numinous and properly transcendental experience. This is not to say I can promise any such thing), can be said without it inflicting itself from the outside the window opens on to, the tyranny of light, the problem with which we are afflicted which no amount, but for some unnecessary cries, of pressing on the wound will bring to expression.

So it goes. . . and if I ever get to ② movement but not this movement, which is unnecessary, will have to be addressed. To restate—I am consciously resisting going from ① to ② without that necessity, the necessity of a well-formed problem, so this is going to be the task of these steps I am taking: forming it as well as I can before moving on. . .

It is something that came out at me, which, beginning the current entry, I thought was the problem, from a PhD. defense a friend asked me to attend online. Brian Massumi was one of the examiners. Avoiding the most obvious description of the dissertation, that it piled abstraction on abstraction, true, that is, to his philosophical commitment to Deleuze and Guattari, of whose A Thousand Plateaus he is the English translator, and their shifting of abstract onto the diagrammatic (about which more in ②), the abstract that is in opposition not to the concrete but to the discrete, he said the dissertation had no examples.

In this it was very unlike Deleuze and Guattari's work, always in reference to examples, from which it does not generalise to reach problems but abstracts from the discrete points those examples articulate to reach what is exactly an abstract (a machine less for being determinate than in movement) machine.

He said it resembled a Leibnizian monad, but that it had no windows and did not open to the outside.

~~~~.~~~~