freedom, distraction, the interval & emotion

On page 29 of (Andrew Goffey's translation, Minnesota 2018, of) David Lapoujade's Powers of Time: Versions of Bergson (French: Puissances du temps, 2010) we read:

The free act is the integral of the whole history of the person—the integral of its sentiments, its thoughts, and its aspirations.

Attributing this clarification to Bergson, he writes of emotion that appearing as irrational is proper to its dynamic series, taking into account a subterranean logic that expresses a sort of law of curvature. Then,

Even if the curve of this dynamic series necessarily has a reason for Leibniz [whose views on these matters run for him in parallel to Bergson's], it can nevertheless appear as irrational as long as [quoting Leibniz] "there must be reasons, which are like abysses exceeding everything that creatures can grasp." In one case as in the other, freedom is analogous to the obscure number of a curve that the whole person expresses by means of decisions and "free acts" that are sometimes incomprehensible.

The role of this curve it seems is, in a subterranean manner, to triangulate Leibniz and Bergson with Deleuze, because on the next page Lapoujade writes:

Does one not rediscover here the differential element that we have been seeking since the beginning?

And perhaps he is right. Perhaps this is the version of Bergson we should be seeking, that is, Deleuze's. Lapoujade begs the question, since nowhere does he say why we are seeking the differential element in his discussion of freedom, and freedom is where he starts. Deleuze starts with difference, hence the differential.

Deleuze's version of Bergson is where quantitative and qualitative multiplicities meet in the differential belonging to the calculus, for which Deleuze goes to Leibniz and not Newton. Bergson's version of Bergson is of the quantitative multiplicities of number being in the realm of physics and qualitative multiplicities of duration (and emotion) being in that of metaphysics. That is, one belongs to science, one to philosophy.

This curve, the image of a curve, evoking a curved spacetime, seems to me the best place to stop reading Lapoujade. Since the beginning of the book I had had problems with where Lapoujade set the stakes.

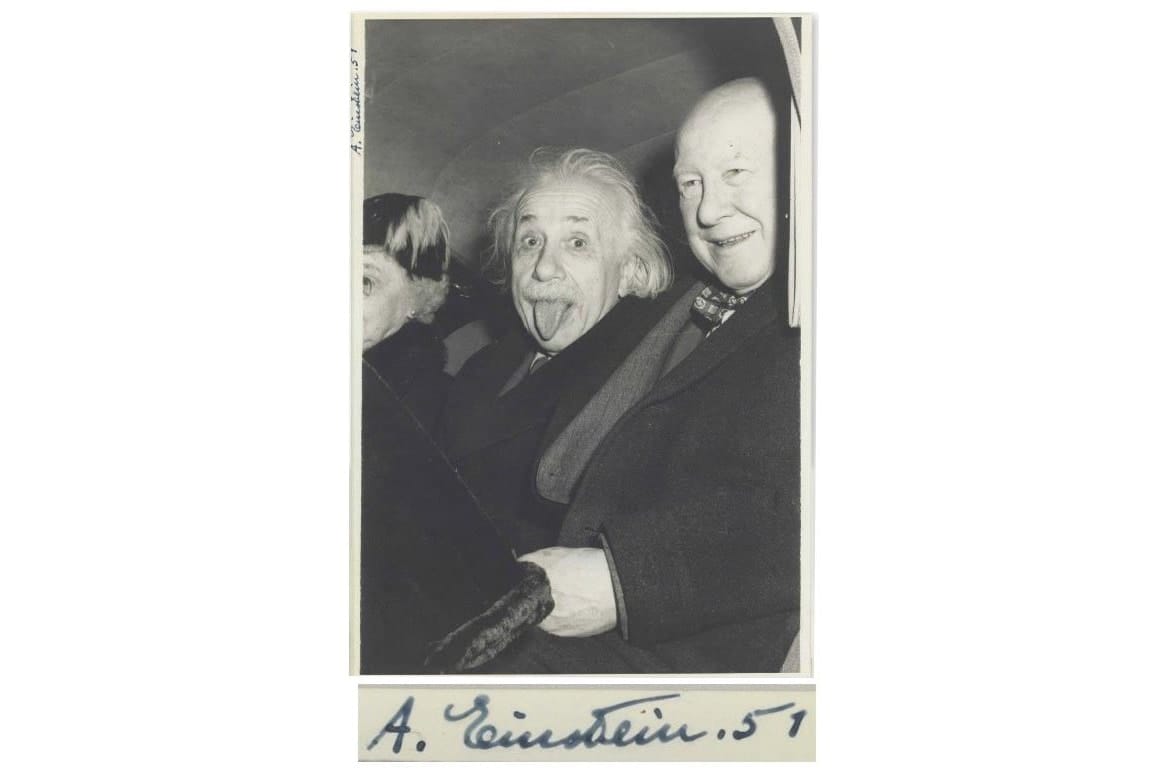

Now we know that Deleuze eschews the troublesome notion of duration, which Bergson states is his fundamental insight—troublesome since the famous meeting between Einstein and Bergson, 6 April 1922, documented by Jimena Canales, The Physicist and the Philosopher, 2015, (for a summary see here) which reading between the lines appears to have been a bit of a set-up engineered to dethrone Bergson from primacy in the popular imagination, by way of Bergson's view of time, of which Einstein was cursorily dismissive, rather than because of it. Deleuze sidesteps an issue that would have made his life difficult (although he smuggles into his philosophical books a fair whack of mysticism, as well as anti- and pre-scientific thought, to be adjudged anti-Einstein in the era of the poking-tongue-out-at-the-authorities version might have spelt career death) in favour of the calculus, that is, in favour of the mathematical tools his younger contemporary Alain Badiou, exceeding or literalising this impulse of Deleuze's, makes first philosophy.

Without questioning it, Lapoujade accepts Deleuze's authority in this matter. What's strange is that Bergson is explicit in contrasting the quantitative multiplicities of number with qualitative multiplicities such as are found in the experience of lived duration. In other words, qualitative multiplicities are secondary to duration. They are how we know it, and have an epistemological role for Bergson, not the ontological one of time, of philosophical time, which is, he says, absolute and real—which language immediately betrays, as space—and not scientific time, the famous spacetime, which Einsteinian mathematics merely puts to work, makes function in the physics of what Lingis calls the carpentry of the world. For one time is useful. Recall, Bergson was anti the utilitarian world because of its falsification of an underlying philosophical truth, whence also the sedimentation of misunderstanding surrounding Bergson's term élan vital. This truth, which Einstein dismissed, saying it doesn't exist, is time.

The time of the philosophers does not exist. –Einstein, 1922

Yes, Leibniz might be right but not as Lapoujade reads him. In view of Bergson, his "abysses exceeding everything that creatures can grasp" rather resemble the intervals of duration than those which are strictly irrational. Or it is number and ratio's inadequacy to them that constitutes their irrationality. Personally I prefer the notion of the creative abyss of primordial chaoses which are everywhere in and around us, like micro black holes, sucking us into timescales that have the madness of eternities.

That's where I would situate Lapoujade's emotions. It is where I have in my work with Minus Theatre: the free creative energies of the powers of being affected able to suspend time. It was this suspension Justin Clemens noted in his attendance of our production Visit Me Genius, at Lot23, 2017, something he suggested that was difficult to do, but we did it. And I hope Minus continues to do it because this is its élan vital.

A small clarification of this term is called for. On it it is wagered that Bergson is a vitalist, not for me. (Neither, although it has been said, is he a phenomenologist. Lapoujade makes him a phenomenologist of the emotions, the qualitative heterogeneity of which derives from the massed confusion of passive syntheses—of association—comprising them.) For me it's a question of practice.

It's a matter of practice: is it more productive, not in terms of utility but creatively speaking, to situate the impulse driving us in the past, in memory or the immemorial, or to sense it vaguely flickering up ahead?

Language always verging on betrayal, am I speaking of the future? If so our natural tendency is to frame such an impulse as we are following, if it is in the future, as a possibility. We would be encouraging clairvoyance to assure us it is there, when that reassurance automatically engages our recognition and our recognition situates it in the repertoire of stories we already tell ourselves, in the realm of what we know. Even to make it knowable, to say the flickering form of a figure that runs ahead is something we can know goes too far. No, not far enough, not risky enough, because it can't be represented.

In the attempt to grasp it in language we are grasping the language—and that perception of language is we know called poetry. Poetry too, if it be not the expression of an inward state, emotion say, goes in search of a form which calls to it. Like a Siren, this would be the original voice.

I have opposed theatre and therapy (I have while also granting that what theatre does is inherently therapeutic; and vice versa, what therapy does is inherently theatrical, see Freud! or the dandiacal Lacan!): therapy goes by way of the evidence on the surface, in the present, to what it omits, which is like the black holes I mentioned earlier, the evidence on the surface being the particles radiating from the aura by which the extent of the omission may be measured, that is, the trauma. For theatre the trauma is in the future, simply. Suspension, you could say, occurs at the entrance, where space and time collapse, of a black hole.

For simplicity's sake, to clarify, let us say that the most creative way to approach what drives us in our movements of perception, life being one, what gives us or anything an élan which is vital, is to say that it exists in the flickering potentials of the present which it does not resemble, but in which it exists, is virtually there. The élan vital.

Almost (this almost might explain its return as that which we never quite end up saying or doing). Then time does not mediate, delay or defer the arrival. The oncoming is in time and of time. Duration. So the élan vital is the work of the imagination. It is what the imagination does. Imagination puts the movements of perception to work to actualise the unique figure of the virtual form belonging to it.

It is unique in the sense of being intimately enfolded and involved, just like the private personal wounds probed by therapy. Unlike them however because intimate for there being no mediation. None of the mediation of tools to probe, mathematical or philosophical, theatrical or therapeutic. Perception enwraps what it would be rather as a virtual form than an omission. So it urges forward.

Now some have seen in this determinism, the attributes of perception moving to determinate ends, since the ends are, like the Tor in Kafka's story, for that one alone. This does not account for how perception unless carefully attended to can lose sight of what is meant for it alone. Again, like the door or gate in Kafka's story.

"Niemand sonst konnte hier je zugelassen werden, denn dies Tor war nur für dich bestimmt. Jetzt werde ich es schließen."

Noone else can ever be admitted here, since this gate was meant only for you. Now I will shut it.

–Kafka, 1915

This is not at all to say that the imagination is mine alone. It is as little mine as the poetic voice is personal, the voice in poetry containing the movement by which it wants to perceive what it imagines, its élan vital, pulling it forward to the sweet spot, every now and again, where it is suspended. As a kid I remember being fascinated by the idea of suspended animation in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, not so much by the literal suspension of bodily function but by the poetic possibilities of what was suggested by these two words being brought together—so I ought to say, the sweet spot not where but when it is suspended. The suspension is of any duration whatsoever, and this was part of the fascination: to be suspended for instants or for eons at a time; and then also to wake up, having dreamed, not having dreamed? I asked this, with the impression of only just having gone to sleep. Not the apes, this was the appeal of Planet of the Apes, 1968, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, and not the evolutionary succession of our species, in which it is only latent: the devastation of the final scene.

For me neither Charlton Heston's recognition and accusation, YOU MANIACS! YOU BLEW IT UP! AH, DAMN YOU! GOD DAMN YOU ALL TO HELL!, nor ours was really the point. It was the potential for time travel that physics, with its images of clocks and twins, set out, with a kind of nonchalance about its cruelty. Determinism shares it and the block universe lands like a brick on the hopes of those like those in Star Trek who boldly go, but space proves not to be the final frontier. Time has the last (silent) laugh.

Writes Lapoujade in Powers of Time:

freedom is analogous to the obscure number of a curve that the whole person expresses by means of decisions and "free acts" that are sometimes incomprehensible.

This does seem to be the view shared by physics and by the physicists whose madness, whose desire to eat the world Benjamín Labatut grasps fully and whose novels, When We Cease to Understand the World, 2021, and The Maniac, 2024, so clearly convey. (see here) The perceptual movement, whether of science, and in the language of mathematical functions, or writing novels, participates in the unconscious; but not inasmuch as what drives those movements—tragic flaws, manic and comic appetites—as of what draws them: the élan vital of their impersonal imagination.

Each movement could not occur without that freedom, also Lapoujade's theme. He however finds it along the curve of the differential, as if since the beginning there was a curve like imagination unique but to the personal and inward associations of emotions. I believe Bergson to be saying that freedom is not an emotional fact but, having different degrees from the pure perception of an inorganic particle to the impurity of embodied perception, a physical one. Like perception, or, for Deleuze—transcendent to the terms which actualise it—like structure, it is outside. (The Logic of Sense, 1969/2004, 356)

Its specific outside for us resides physically in the complexity of the brain and central nervous system. Again Bergson is quite explicit about this, the brain is not a place where thoughts occur and images are seen. It is not any place at all but a delay, the reason being that of its complexity for the time it takes those movements commonly associated with a stimulus to reach those commonly associated with a response. Neither one according to his model follows the physical laws of cause and effect however either one can fall victim to what is dictated by habit and routine. To make a free movement requires a decision of which at first one must be unconscious.

At first: spontaneous acts are rare; which is to say spontaneous movements are, whether in the perceptual attribute of philosophy, thought or pure thought, in that perceptual movement, or in that mental action embodying perception proper to mathematical calculation, embodied in number, or in the words and lines which embody poetic movement and in that perceptual movement of bodies in time specific to theatre. In every case initiating a movement that has its own duration, each has a freedom it chases after that is of the virtual image and has the élan vital. Further we may extend the model to the movement of a developing embryonic brain, its fulfillment always shy of perfection for the parts, the cells and contents of the cells, through which its perception is embodied.

Why unconscious? For two reasons: 1) the contents of the consciousness are not those of perception; 2) consciousness is assumed to comprise definite processes, even where feeling and emotion are concerned, which feeling and emotion are always the product of previous associations. In short, the brain is limited both by that assumption and by consciousness being identified with perception.

I think Bergson is saying that the brain is itself a perceptual movement in its transformations over time. If it already knew what it was (notice how language distorts the present process by setting it in the past; notice also how knowing equates with qualitative multiplicity) becoming it would lack the vital impetus, the flickering that occurs to the neurons and nowhere else, to become it. (See also "a tree imagines it's a tree.") Perception is largely unconscious because it requires the freedom of the unconscious to become what it is. (Only as a process does it ever arrive there. Hence the criticism of process-philosophy would run: a process has virtual and actual components but the virtual ones once actualised do not resemble the actual—as little as they are either recognised to be or will represent it. And let it not be thought, as if in a vicious circle, that what results is taken up again in the process!)

These themes, lack of resemblance, representation and recognition, are in Deleuze (see Difference and Repetition, 1968/1994) and so is the movement from the actual to the virtual. Bergson adds that this movement is of a distinct duration, knowable through its interpenetrating qualities (for me those of perception), the qualitative multiplicities of duration, and not knowable but only broken down into the points through which the movement passes from the point of view of a completion effected or presupposed—the quantitative multiplicities that exist for the sake of function and utility. (If it were knowledge this breaking-down were about or pursued we might say that knowledge occupies the same sweet spot where it is suspended, every now and again, by the flickering of its own élan vital.) The impulse must be there for the movement to be initiated—and, as we've said, it is the more creative option to have a movement to than a movement from. Not only this, if at first it must be unconsciously this is because to be initiated it has to come from outside the contents of consciousness which are the represented because actual, the resembled because already actual, and the recognised because of a movement synthesised in association of a perception already achieved and actual.

Perception, therefore, requires the freedom of an unconscious. This is what I think Deleuze and Guattari mean when they say in A Thousand Plateaus, 1980/1987 (the latter date in English translation), an unconscious must be made. I will give an example.

I am returning to an example I passed over without comment writing before, part 1, and then after, part 2, Minus Theatre workshop 8. There I wrote, "a good naturalism looks past the act of speaking or distracts away from it, to give the unconscious more freedom." In part 1 of Minus Theatre workshop 7 I took my definition of a good naturalism from Declan Donnellan's The Actor and the Target, 2002, as one that plays the target, a neutral but singular value, invariable n, and, because too general, not the character, variable N. Donnellan's advice is to pursue the singular value, n = target, over an actor trying to convey a whole character, N, which, anyway is impossible on two counts: there are no whole characters; an actor can never become wholly conscious, since they have a body of which they are largely unconscious, of what they are conveying.

The answer is like the Zen archer, and so as always with Zen slightly humorous, to let go even of so definite and determinate an action as shooting a target. A great deal of discipline goes into being so distracted as to let the perceptual movement complete itself on its own. This distraction is what I am equating with giving the unconscious more freedom. Sighting, drawing the bow, releasing the arrow will be different each time (by setting it in the future a fact which language distorts) and not occur on the curve, but in the interval of duration which coordinating perception is that of the virtual image, on which the Zen archer's approach to perfection is not premised, but which she or he pursues.

In the example of speech I suggested that actors can learn all those lines because of being distracted away from the semantic or intentional aspects of dialogue, as either progressing the action or expressing a passion on the part of the character. They can memorise all those lines, entire scripts of them, from being carried away, distracted, by a perceptual, sensory-motor, sensory-muscular movement which is free of conscious associations. It even tends to be free of emotional content too, enabling actors after having memorised their parts to 'colour' them in different ways, taking the colour metaphor, as far as making small adjustments of hue and intensity, as well as finding rhythms and speeds to match. This may sound mechanical, as if tightening or loosening one's delivery of lines were like tightening or loosening nuts and bolts, but it is entirely pragmatic.

It may sound mechanical for lacking the emotion that Lapoujade says is our door to duration. But think, if an actor should recognise themselves in a character, no matter it is variable, N, this would automatically impose a limit on their freedom of movement; if they should seek resemblance, the same; and, if seeking representation, through or of a character, they would limit the range of the points through which that movement would pass, constraining the limitless qualities which they might express to N = 1.

From the example what comes to mind is that the role of playwriting and of playwrights (Donnellan, I think it is, points out the pragmatic implications of a play being wrought as a wheel is wrought) is, if the purpose is to have them performed and not read as literature, to distract with their words from the purpose of their plays. (This gets as far from utilitarian playwriting as one can get. For utilitarian playwriting see here.) The words are written to be unconscious movements, each an opportunity for the freedom of the unconscious.

Language, that giving rise to reason and writing and thus setting ours above and in custodianship over all the other species, which had been considered the decisive conscious act is shown to be no more meaningful than the prattling of an infant, just a ruse, letting perception look past the act of speaking or distracting away from it, to give the unconscious more freedom.

Obversely, the development of speech in children starts from prattling. Vocal sounds are stages of encounter with the world and are produced in the suspension, where meaning is fluid, that gives to them a force of animation which is sheer movement and momentum. Toddlers begin to see the effects on the world of the sounds they make—and there is no first to speech here, since from the beginning their cries have been as effective—that's when the experimentation starts: colours are mixed, hues and intensities are subjected to variation. The speech of children optimises the distraction of sense for the sake of effect. That is, the opposite is true from the speech of children being direct. As the body is for Bergson, the first speech has the body as centre of action, but that it is for experimentation it would be thought totally selfish.

This brings me to a final question:

I might even have assumed it answered when I wrote in my notes on Minus Theatre workshop 9 that with their cilia and flagella single-celled organisms have the same parts they use for movement as they use for perceiving the outside world, which perception is a movement to find nutrition. The question is, taking into consideration that each of our perceptual movements engages a distinct and invariable motivation, n, as its target, What do we move for?

Energy, I said in those notes. We move to what attracts us; which every religion tells us does not take actual form. And for Lacan and Freud it is what we lack, desire. On a social and industrial level, it is our well-being, which every religion has an argument against. My point is that it, whatever it may be, already exists, is in the perceptual field.

Every spiritual discipline and even some practical ones tell us that conscious striving will be of no assistance to us in making it be known. The knowledge we have of prior instances has been as good as children's experimentation with language: that is, extremely useful for seeing its effects. From practical experiment we have seen and can measure the effects, whether deleterious or beneficial, of our activities.

Energy I said earlier because of an association I had made—there it was with the flickering of a virtual form, Eiseley's spotted dog (see Minus Theatre workshop 6, subheading "the image of the flicker – and Loren Eiseley")—with what here I have invoked as élan vital. And I have used for my example what comes from the interval of duration for theatrical movement, that in my practice of theatre I have as soon related to the neutral body as the active one, suggesting that the neutral body is more sensitive to being affected. Then this has been all to do with conscious movement and how it blocks those powers of being affected.

Whereas in a workshop I would get tied up in lengthy explanations, writing I can easily make the leap from energy to élan vital; and whereas in a workshop I might say what we are learning is the language of theatre, although it requires context, writing I'd sooner say theatrical perception. Whether language or theatre, for me to make those moves I've needed to have, never in clear sight, but always seen out side of my eye or thought out side of my mind, a restless presence. And I would as soon say I've felt it as had the idea of it, so my answer, energy, since it crosses the boundary (doesn't close it) between a physical need, like food, and an aesthetic one, of feeling, albeit one of an invariable and singular kind, n, seems almost sufficient. It leads me to say that, apart from food humans need dreams. And that the themes I have handled of here, of freedom, distraction, the interruption of the interval and emotion, are brought together by dreams.

I have in mind the testimony of Banias, an eight-year old girl living in Gaza. Producer of This American Life, Chana Joffe-Walt, wanting to know what's happening on the ground, is talking to her friend, a reporter in Gaza, Maram Hamaid, when her daughter Banias interrupts the conversation. From this interruption, over a series of phonecalls dominated by Banias's narration, grows an entire episode of the podcast. Banias is asked what the children want above all (I believe I am getting this right), the answer comes: we want our dreams back.

The narration in turn is interrupted by Joff-Walt's and Hamaid's conversations. These act as a foil to Banias and there is an act of betrayal with which Joff-Walt is complicit. From it, along with the title of the episode, "The Narrator," we get the impression that Banias is an unreliable narrator of the reality of her experience. As Banias's stories come to have a double-edged meaning, we get the impression that this is the impression, whether consciously or not, Joff-Walt goes about to create. As a listener it's hard not to hear the adults' version both as a pretense of having a clearer grip on the reality and as of wanting to inflict it whatever the cost.

This American Life, episode 849 December 13, 2024