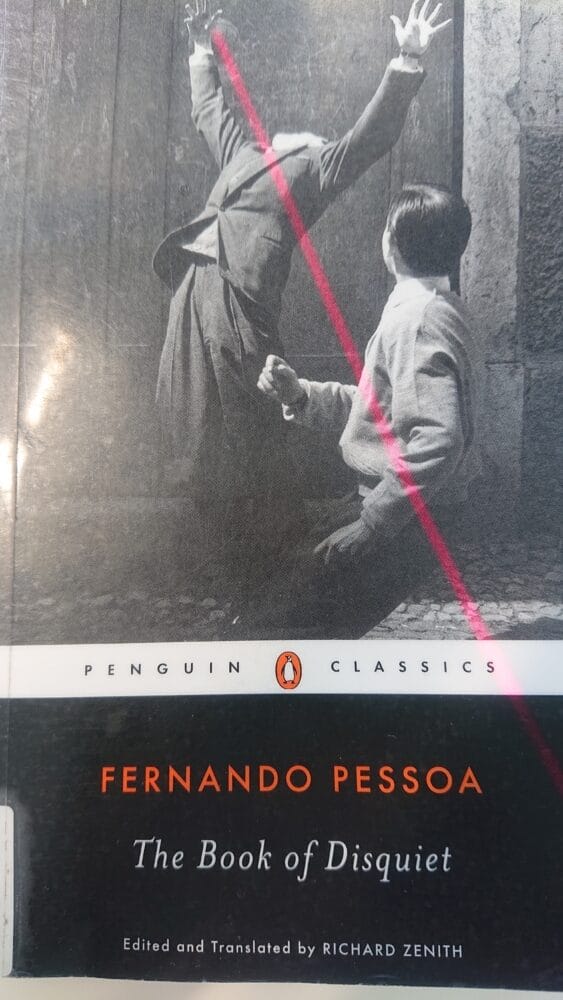

#370 Fernando Pessoa. . . The Book of Disquiet □ the ethics of representation. . . & cascade ■▣◼▪ ⚫ and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar @ The Time Regulation Institute

I never let my feelings know what I’m going to make them feel. I play with my sensations like a bored princess with her large, viciously agile cats.

I slam doors within me where certain sensations were about to pass in order to be realized. I quickly clear their path of mental objects that might cause them to make gestures.

Little nonsense phrases inserted into the conversations we pretend to be having, meaningless affirmations made from the ashes of other, equally meaningless affirmations. . .

– Your gaze reminds me of music played on a boat in the middle of a mysterious river with woods on the facing shore. . .

= Don’t say that it’s a chilly moonlit night. I abhor moonlit nights. . . There are people who actually play music on moonlit nights. . .

– That’s also a possibility. . . An unfortunate one, of course. . . But your gaze evidently wants to be nostalgic about something. . . It lacks the feeling it expresses. . . In the falseness of your expression I can see many of the illusions that I’ve had. . .

= I can assure you that I sometimes feel what I say and even, despite being a woman, what I say through my gaze. . .

– Aren’t you being harsh on yourself? Do we really feel what we think we’re feeling? Does this conversation, for example, have any semblance of reality? Surely not. It would be unacceptable in a novel.

= And with good reason. . . Look, I’m not absolutely certain that I’m talking with you. . . In spite of being a woman, I made it my duty to be an illustration in the picture book of a made artist. . . Some of my detail is overly precise. . . I realize it gives the impression of an overwrought, somewhat forced reality. . . To be an illustration seems to me the only ideal worthy of a contemporary woman. As a child I wanted to be the queen of one of the suits in a deck of old cards we had at home. . . This seemed to me like such a compassionately heraldic vocation. . . For a child, of course, such moral aspirations are common. . . Only later, when all our aspirations are immoral, do we really think about this. . .

– Since I never talk to children, I believe in their artistic instinct. . . You know, even now as I’m talking I’m trying to fathom the true meaning of the things you’ve been telling me. Do you forgive me?

= Not entirely. . . We should never plumb the feelings that other people pretend to have. They’re always too intimate. . . Don’t think it doesn’t hurt me to share these intimate secrets, all of which are false but which represent true tatters of my pathetic soul. . . The most pitiful thing about us, believe me, is what we really aren’t, and our worse tragedies take place in the idea we have of ourselves.

– That’s so true. . . Why say it? You’ve hurt me. Why ruin the constant unreality of our conversation? This way it almost becomes a plausible interchange at a table set for tea, between a beautiful woman and a dreamer of sensations.

= You’re right. . . Now it’s my turn to ask forgiveness. . . But I was distracted and really didn’t notice that I’d said something that makes sense. . . Let’s change the subject. . . How late it always is! . . . Don’t get upset again — the sentence I just said, after all, is complete nonsense. . .

– Don’t apologize, and don’t pay attention to what we’re talking about. . . Every good conversation should be a two-way monologue. . . We should ultimately be unable to tell whether we really talked with someone or simply imagined the conversation. . . The best and profoundest conversations, and the least morally instructive ones, are those that novelists have between two characters from one of their books. For example. . .

= For heaven’s sake! Don’t tell me you were going to cite an example! That’s only done in grammars; perhaps you’ve forgotten that we don’t even read them.

– Did you ever read a grammar?

= Never. I’ve always despised knowing the correct way to say something. . . All I ever liked in grammar books were the exceptions and pleonasms. . . To dodge the rules and say useless things sums up the essentially modern attitude. Did I say that correctly? . . .

– Absolutely. . . What’s especially irritating in grammars (have you noticed how exquisitely impossible it is for us to be talking about this?) — the most irritating part of grammars is the chapter on verbs, since these are what give meaning to sentences. . . An honest sentence should always have any number of possible meanings. . . Verbs!. . . A friend of mine who committed suicide — every time I have a longish conversation I suicide a friend — was going to dedicate his life to destroying verbs. . .

= Why did he commit suicide?

– Wait, I still don’t know. . . He wanted to discover and develop a method for surreptitiously not completing sentences. He used to say that he was searching for the microbe of meaning. . . He committed suicide — yes, of course — because one day he realized what a tremendous responsibility he’d assumed. . . The enormity of the problem made him go nuts. . . A revolver and. . .

= No, that’s preposterous. . . Don’t you see that it could never be a revolver? A man like that never shoots himself in the head. . . You understand very little about the friends you’ve never had. . . That’s a serious defect, you know. . . My best girlfriend, a ravishing young man I invented. . .

– Do you get along?

= As best we can. . . But this girl, you can’t imagine. . .

The two figures sitting at the table set for tea surely didn’t have this conversation. But they were so well groomed and dressed that it seemed a pity for them not to talk this way. . . That’s why I wrote this conversation for them to have had. . . Their gestures, mannerisms, playful glances and smiles — those short interludes in the conversation when we stop feeling our own existence — clearly expressed what I faithfully pretend to be reporting. . . After they go their separate ways, each marrying someone else (since they think too much alike to marry each other), if one day they happen to look at these pages, I think they will recognize what they never said and will be grateful to me for so accurately interpreting not only what they really are but also what they never wished to be nor ever knew they were. . .

If they read me, may they believe that this was what they really said. In the words that they apparently heard from each other there so many □ things missing, such as the fragrance in the air, the tea’s aroma, the meaning of the corsage of □ which she wore on her chest. . . Although never stated, these things formed part of the conversation. . . All these things were there, and so my task isn’t really to write literature but history. I reconstruct, completing what’s missing, and this will serve as my excuse to them for having eavesdropped on what they didn’t say and wouldn’t have wanted to say.

□

. . . Levrero recalls Pessoa. . . Pessoa recalls Levrero. . . except for something we might call the ethics of representation, which in this context means providing the map of the territory without the signposts; so, a certain reserve; a reserve that in the last instance would prevail in favour of what is given in representation, the setting, set-up, the textual mise-en-scène, assuming it already given and assuming it unnecessary to add to, without, at least, risking redundancy. In the meantime representation has become more slippery and at once more solid, so that the risk is real. Or is of the real, which in Levrero‘s case is exactly the meaning of the transcendental in transcendental experience. Pessoa could afford a greater margin, a buffer-zone, of indiscernibility . . . representation didn’t seem to require the delicacy, the lightness of touch, in negotiating it does for Levrero and those after him, especially that caution which it demands of writers of autofiction and, in particular, writers of autofiction for whom the notions of self and presence have become problematic, and, although solid, unstable, thereby dangerous, so that the writer with too heavy a hand runs the risk of being crushed between, as if caught in a set of revolving doors, self-presence, presence-self, or, heavy footed, of slipping, as if on a flight of marble steps, presence, presence, presence, self, self, self . . .

⚫

. . .here I am this morning, struggling to write my memoirs in the oversized notebook before me. In fact I woke up at five o’clock—much earlier than usual—with this very task in mind. All the good-natured and industrious employees at Clock Villa . . . In short, I have tried to arrange the events of my life into some semblance of order, bearing in mind the many strict rules of what we might call sincere writing: these are never as indispensable as when one is composing a memoir.

. . . A sincerity of this order—disinterested and unconditional—by its nature requires close scrutiny and constant filtering. You must agree that it would be unthinkable to describe things as they are. If you are to avoid leaving a sentence arrested in midthought, you must plan ahead, choosing only those points that will resonate with the reader’s sentiments. For sincerity is not the work of one man alone.

— Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, The Time Regulation Institute, translated by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe, 2013, p. 6