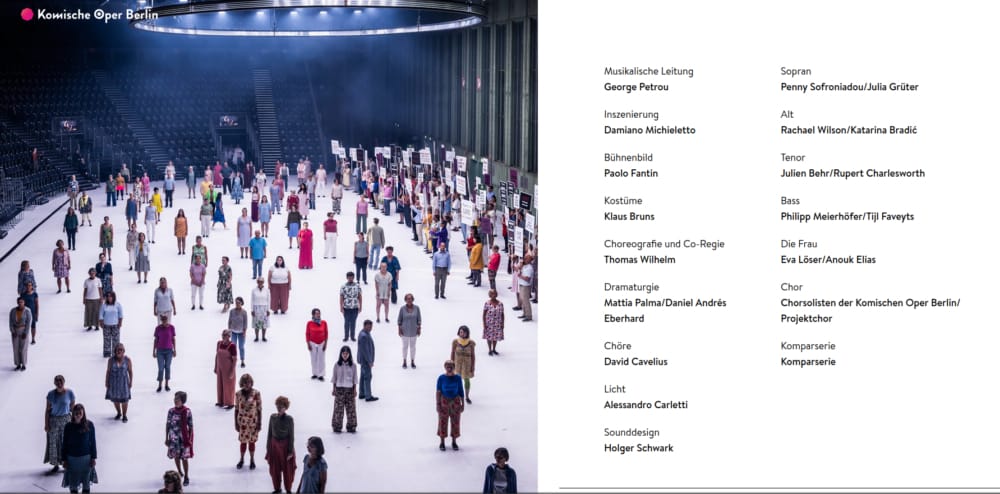

Day 22 – September 22 2024 – Berlin: Damiano Michieletto’s Messiah with Komische Oper at Tempelhof & plus some stops along the way

Flohmarkt, Boxhagener Platz,

to the opera,

air-filled bladders, sound baffles around the outside of the hangar-auditiorium, a kite-symbol and bush-symbol, the kite would be chased, its cruciform structure, and bush uprooted (not burst into flame–which’d be more fun),

interval, no snaps during show, and into second half,

curtain call, (note enlarged polaroids from the by-story of Brittany Maynard, an American campaigner for assisted suicide [see here]),

The performance was outstanding and affecting in every respect except in that of this strange and unassimilated through-line imposed on it as if the oratorio required a story: Brittany Maynard’s story. It, as the Berliner Zeitung said, knirscht and knackt, without, from the friction between Jesus and Brittany (although it is contestable as to whether the work is about Jesus), between one passion and the other, there issuing any spark illuminating either.

It is contestable because Jesus’s in Handel and librettist Charles Jennens’s (an English aristocrat) story is a highly public and political passion: the government and the person of the king, George, is given to be a wonderful counsellor and prince of peace as much as and on the example of the Messiah, in some kind of wishful thinking and, to the glory of the royal patron, who, it is said at its premiere stood for the hallelujah, instituting the custom of so doing; one that was discouraged in this case, as the pre-show lecture explained the reason for why it became so. (This too is open to debate. Did George stand because he suddenly recognised his insignificance, beggared by comparison? or did he think the song was about him?)

Die Verbindung des „Messias“ als eines Wir-Stücks über Hoffnungen mit dieser Ich-Geschichte ohne Horizont knirscht und knackt in allen Gelenken.

— Berliner Zeitung, 22.09.2024

The passion of Brittany Maynard was public, from her campaign for the right to die, and could however be said to be political; but this brings up what the Berliner Zeitung put as the Ich-Geschichte and the Wir-Stück, or Wir-Geschichte, or, pursuing this line, what, although it ought not be thought to account for it, history belonging to George and Jesus, is accounted as Geschichte.

The part of Brittany, unnamed in the production, was played, now this is odd:

… she is unnamed here too. The roles are presented by vocal and not dramatic part as they would be in a traditional production.

She is played by a dancer, who, because she does not sing, is the only nonsinging role, even the stage business is managed by the chorus, is a kind of mime. (Here, called Die Frau, she is named as Anouk Elias.) She does however speak: we hear her pre-recorded, narrating key moments in her story, like this:

When my suffering becomes too great, I can say to all those I love, “I love you; come be by my side, and come say goodbye as I pass into whatever’s next.” I will die upstairs in my bedroom with my husband, mother, stepfather and best friend by my side and pass peacefully.

— source

These I-statements came through the big speaker system to which the chorus and all the soloists and the excellent orchestra, excellent under the direction, the baton, of George Patrou, almost receiving at the end a standing ovation, were all hooked up; the singers by mics without even the bulge of a battery pack being visible. These were the only times we were really conscious of the speaker-system, the enhancement being so subtle and flexible for orchestra, chorus and soloists, that the combination of voices was always spatially specified. In audio terms, this quality gets a visual metaphor, they are visualised. Here, however, the sound of the voices could be tied to the individual singers who were closest to us: there was never a general wash of sound. The better metaphor might be articulation: the sound was articulated rather than either generalised or elaborated. The sonic atmosphere despite the scale of the work and the scale of the venue was intimate. And this goes to the Ich-Geschichte daß knirscht und knackt.

As it was explained in the pre-show address, an odd and oddly compromising expedient to take unless taken under duress of either the backers or the organisation and one owing to the controversy that the production either courted or had already caused, so that the pre-show was like a warning that the interpretation might trigger offense quite apart from the subject-matter of suicide, in this Messiah the cosmic and the intimate are brought together. The soloists are the mum, dad, husband and doctor of the Frau, Brittany Maynard; the action occurs around a dinner table: it is domestic in scale. In fact this was reflected in the Hallelujah. It was pulled back. It was an emotional appeal. And this affectivity, that was a result of conjoining the domestic and the celestial sphere, was carried throughout the production, to the extent that not only was the Messiah performed and not a concert version it was embodied. But, it must be said, these were private bodies. And the affect was carried as much by the brilliant playing of the orchestra (original instruments?), the musical direction, as by the emotional charge in the singers’ voices and bodies (although did they need to gesticulate so much?), but the Ich- and Wir- did not mesh. I even thought is this a broken machine? is that why it works?

No, it was, from a director’s point of view, like one of those games used in workshops (like those The Bear TV series presents onscreen undigested, by the exigencies of the plot and narrative progress, in undigested chunks), exercises used to elicit emotion and intensity. These are a part of what Declan Donnellan calls the invisible work and are usually stripped out from the visible work, in performance, to leave the affective intensity, without the scaffolding of the exercise, to do its work, and, by communicating actual emotion, revive, say, a dead text. Do we need to know, by using the Method, Strasberg’s Ich-Geschicte-lich adaptation of Sanislavsky’s more-like Wir-Arbeit, that the actor is thinking of Janola to produce tears?

In other words, Brittany Maynard’s story was like the scaffolding that the Messiah didn’t need. Stripped away, the performances, all of them, were strong enough to carry the piece, the Wir-Stück, emotionally: the visible work did not need it. The tunes are good. The text is a bit clunky, but having some blood in its veins, we didn’t need as an audience, to know where from. And for all that there were other choices which might have been made to suffuse the experience with what in our contemporary world produces strong emotion. For example, the contemporary holocaust, the Wir-Geschichte, of Palestine.

With its talk of government, counsellor, religious support for political ends, think how that might have effected the work! And that scaffold, present in the visible work, it would then be up to the audience to … digest. With a knirsching and knacking of teeth and jaws, the indigestible …

… but this was an excellent piece of work. I’ve never heard the emotional appeal here, a piece that can come across as wiggy and fusty. A going-through-the-motions of an Hallelujah. Now, the restraint in this Messiah was all on the side of the musical direction, under George Patrou’s charismatic conducting.

…

which brings me finally to this theme of ideas about we and I types of community and their different relations to the space: space is a social construct

…