Houellebecq’s Annihilation: excerpts, including space—a social construction, and the aesthetic superiority, to the cultural production of the elite, of popular cultural production: Or, Houellebecq, in whose hands Realism becomes a genre superior to either

Could a politician really influence the course of things? It seemed questionable. Developments in technology could do that without a doubt; and so, perhaps, to some degree, could economic power relations—even though Bruno [based on Bruno Le Maire, France’s Finance Minister] still tended to some degree to see the economy as a sub-product of technology. [see “10 Free Technology Takeaways of 2025“] There was also something else, a dark and secret force which might be psychological, sociological or simply biological in nature, it was impossible to know what it was, but it was terribly important because everything else depended on it, both demographics and religious faith, and finally people’s desire to stay alive, and the future of their civilizations.1

. . . the lack of conviction in a political leader was not necessarily a sign of cynicism, but rather of maturity. Had the kings of France shown up armed with a political programme, a plan of reforms? Never. Nonetheless they had gone down in history as great kings, or on the contrary as appalling kings, for their tendency to fulfil an implicit but precise set of specifications. Not reducing the territory of the kingdom, on the contrary increasing it if possible, either through purchases or more often through wars, while at the same time avoiding increasing the costs of mercenaries to excess, and more generally avoiding any unnecessary fiscal pressure. Avoiding civil wars within the kingdom, in particular religious wars, they had always been the deadliest, which had been achieved by unambiguously designating a single dominant religion; other minor religions could be granted broad religious licence, on condition that they never forgot that they were tolerated at best within the national territory, and that that tolerance would always be at the sovereign’s discretion. Perhaps increasing the prestige of the kingdom by erecting monuments and supporting the arts. For some centuries this ideal programme had ensured the prestige of the curious partnership of Richelieu and Louis XIII . . . The task of the presidents of the Republic, contrary to what an exaggerated belief in progress, and more generally in the importance of historical changes, might have led one to think, was essentially the same as the task of kings.

— Michel Houellebecq, Annihilation, translated by Shaun Whiteside, Picador, 2024, pp. 429-431

. . . the wider public was of the essence, it was now, since the Beatles and perhaps since Elvis Presley, the norm of all validation, a role that the cultivated class, having failed both in ethical and aesthetic terms, and also being seriously compromised on the intellectual level, was no longer qualified to hold. Since the wider public had thus acquired the status of a source of universal validation, its programmed debasement was a bad idea . . . and could only lead to a sad and violent end.

— Ibid., pp. 492-493

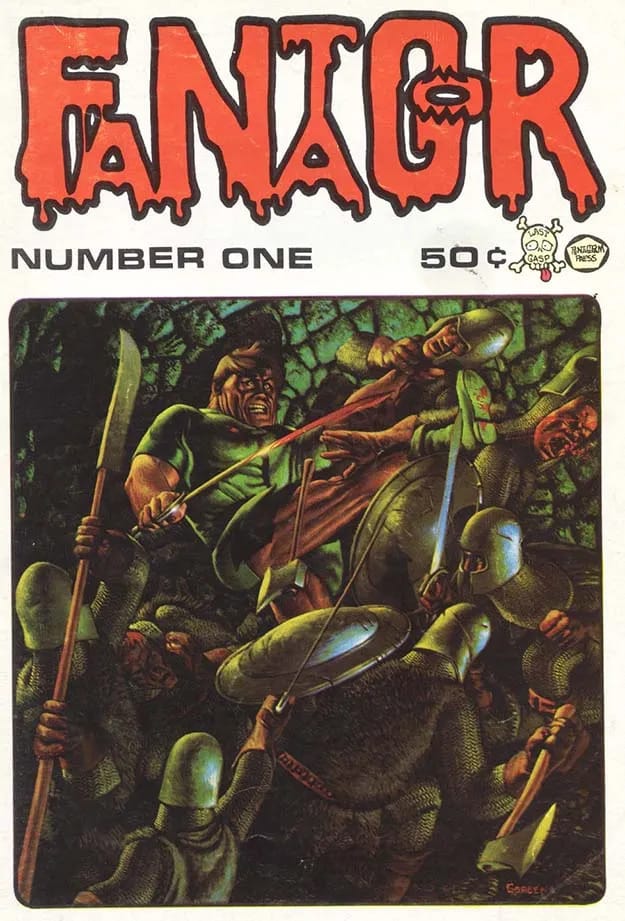

. . . the ideological, political and moral character of the Second World War: however bloody it might have been, the fight against Nazism2 had not been limited to the possession of territories, it had not been an absurd fight, and the generation that had triumphed over Hitler had done so with the clear conscience of fighting in the camp of Good. The Second World War had thus been not only the usual kind of foreign war, but also in a sense a civil war, in which one was fighting not for ordinary patriotic interests, but in the name of a certain vision of moral law. It could thus be compared to revolutions, in particular to the mother of them all, the French Revolution, of which the Napoleonic wars had been merely a stupid extension. Nazism had been a revolutionary movement in its way, aiming at replacing the existing system of values,3 and had attacked all the other European countries not only to invade them, but also to regenerate their system of values; and, like the French Revolution according to de Maistre, there was no doubt about its satanic origin. Thus the baby-boom generation, the one that had triumphed over Nazism, could in many respects be compared to the Romantic generation, the one that triumphed over the Revolution, . . . It also corresponded to that very particular moment when, for the first time in world history, popular cultural production had proved to be aesthetically superior to the cultural production of the elite. Genre fiction, whether thrillers or scifi, was broadly superior, at that time, to the mainstream novel; the comic-book outclassed by far the creations of the official representatives of the visual arts; and most particularly, popular music made a mockery of subsidized attempts at ‘experimental’ music.4 In spite of everything, it had to be agreed that rock, that generation’s greatest artistic phenomenon, did not quite attain the beauty of romantic poetry; but it shared its creativity, its energy, and also a kind of naivety.

meanwhile, at the White House5

. . .

- space—a social construction ↩︎

- cf. the demoralising wars, and those frankly immoral ones, being fought today, with their antecedents in Korea and Vietnam ↩︎

- cf. “value creation” as the goal of tech leaders in “10 Free Tech Takeways 2025,” and Thiel’s revolutionary thinking near the end of that text ↩︎

- see John Mauceri, The War on Music, 2022; discussed here ↩︎

- doing the work of Curtis Yarvin ↩︎