insular discovery of freedom . . . {illus. Susan Hauptman} .

Neill Duncan (see “for Neill” here): In a funny sort of way, the Primitive Art Group opened my horizons musically, but in other ways it made me narrow-minded. . . . We were doing this edgy music and that other stuff’s so straight. Everything else was shit. We had that attitude. We were reacting against the status quo. We were very insular. We were focused on the idea that the only good music in New Zealand right now is what we’re doing. I always remember Anthony, . . .

— Future Jaw-Clap, Daniel Beban, 2024

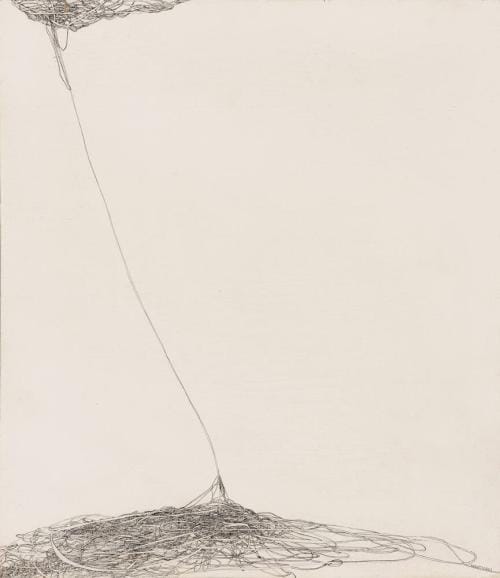

— Susan Hauptman, Line Drawing #12, 1970

Today we use the word only in its political sense, and how unfortunate for us. For I fear that those who see freedom solely as a political concept will never grasp its meaning. The political pursuit of freedom can lead to its eradication on a grand scale—or rather it opens the door to countless curtailments. It seems that freedom is the most coveted commodity in the world: for just when one person decides to gorge upon it, those around him are deprived. Never have I known a concept so inextricable from its antithesis, and indeed entirely crushed under its weight.

. . .

Where does it come from? And how does it vanish with such stealth? Are those who bring us freedom the very ones who snatch it away? Or do we simply lose interest from one moment to the next, . . .

. . . no one really needs such a thing in the first place. This love of liberty . . . is nothing more than a kind of snobbism.

The freedom I knew as a child was of a different kind. First, and I think most significantly, it was not something I was given. It was something I discovered on my own one day—a lump of gold concealed in my innermost depths, a bird trilling in a tree, sunlight playing on water. There was no going back; from the moment I discovered it, everything changed: my humble existence, our humble home, the very world in which we lived. In time I would lose them all. Nevertheless I owe all the most precious things in my life to freedom. It has filled my days with miracles that neither the miseries of my early years nor the comforts of today could ever take from me.

— The Time Regulation Institute, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, 1962, translated by Maureen Freely & Alexander Dawe, 2013

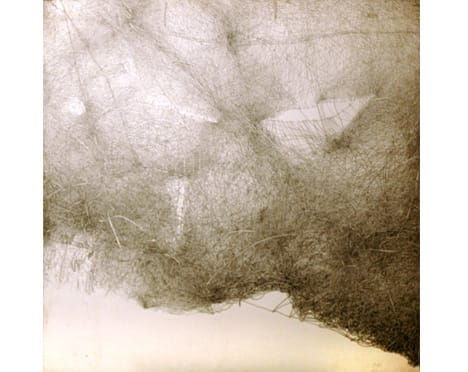

— Susan Hauptman, Untitled, 1970

. . . the Nuclear Horror Show became part of the pressure that eventually led to New Zealand becoming nuclear-free. The zealous horizontal organising of school groups, university groups, religious groups, professional groups and others, of which the artists and musicians were a part, paid off. “That time was just a perfect example of art, unions, churches, everybody in unison. That’s why it worked. That’s the only reason it worked,” says [Nicky] Hager. “It was a time of energy and vigour for everyone, that why they could put together such an incredible show, all those artists just throwing themselves into it. It was the right time for it. There was energy to burn, everywhere.”

“You can’t even get people out of bed these days,” says Debra Bustin.

— Future Jaw-Clap, Daniel Beban, 2024

— Susan Hauptman, Line Drawing #101, 1972