Minus workshop 6, part 1: meaning

In the workshop I did recently, run by author of Matter of Fact: Talking Truth in a Post-Truth World, 2018, Jess Berentson-Shaw for those who work in libraries (there is no guarantee anymore they are librarians) about countering false information, certain statements were made I wrote down that are the pivot-points for her research-practice. Here is one: ours is a brain designed to process information quickly, while the object is to slow down processing and engage critical thinking. A brain does not process according to logic but beliefs, then feelings in the body, which, as a single mind-body system, prompt it to make decisions. Only after having made decisions do we test information by applying logic to the information, or what Berentson-Shaw calls logic. This includes the judgement of reason and the potential for there being conflicting evidence as to the validity or verity of the information.

She said she was shocked to discover that our decisions are based on beliefs first and logic last, and that our test of truth derives from what we are comfortable with believing, with what fits our existing beliefs and values and does not raise questions. For the strategies to counter false information she advocated against conflict, against presenting conflicting information immediately, but preempting any encounter with false information by signposting it with its potential to be false in whatever space (she used the term many times) it occurred. This she called prebunking and inoculation as well: prebunking to be used in the place of directly debunking information by revealing it as false; and inoculation to be the wide-spectrum warning introduced into the mind-body system putting it on alert against potential false information. The second strategy, if that didn't or hadn't worked, she presented was to connect with the beliefs and values of any casualty to false information and to show empathy.

Avoid repeating the false information espoused and after general phrases of agreement with values, like I see you care a great deal about ..., suggest to the person that there exist alternatives to the false one. In a library point them to a book with evidence otherwise. Connect rather than correct. Broaden their mind, but be aware of the resistance you may strike. Whatever information is believed has taken residence in their belief and mind-body system and they might aggressively, since they have every right to, defend themselves.

Lastly Berentson-Shaw presented what she called a truth sandwich, where the slices of bread are correct information and the filling is the falsehood. Spread the false information thinly. Know that any repetition will have the unforeseen consequence, even if couched in negative terms of It is not true that ..., of reinforcing it. Begin your truth sandwich with a value statement, because people, she claimed, generally have good intentions.

The example she gave amused me because it was that libraries value your privacy and therefore protect your private information. They will not sell or share it with any outside parties or companies. Auckland Libraries' Vega catalogue has cookies which, in breach of this most basic library value, share private information from your browser with third parties. This is not by accident, but by design, since the vendor is a logistics company, with a wholly different set of values to that supposed to belong to libraries.

...

Levi R. Bryant, Larval Subjects weblog, on The Strange Case of Imaginary Beings:

I’m left wondering were it not the case that classifications, myths, ideologies, etc., not real features of our world producing real effects, why would we spend so much time critiquing these things and trying to, in many instance, destroy them?

I'd previously thought Bryant's name for his weblog to refer simply to Deleuze's notion of larval subjects, those who are emergent rather than able to be fixed in their identity; but of course he could equally be referring to the subjects he deals with in the weblog, that for his part he is neither expressing a final opinion nor passing judgement on them. They are not fully formed. And if this is the case his subjects, emergent and changing, also participate in imagination and flickering out side of mind take virtual form, like imaginary beings.

To say not fully formed and taking a form which is virtual is not the same. Deleuze and Guattari describe the relation of the whole to the parts, which are emergent, nonhierarchical, larval subjects, to be one of a part that is added. The whole is an addition modifying the rest of the parts. It's only in a manner of thinking that we grant it a special status, in another manner of thinking we can revoke it, and say, with Deleuze and Guattari, n - 1.

Bryant in his post names Graham Harman as his interlocutor, whose view, according to Object-Oriented Ontology, of imaginary beings is that they have no independent existence outside of actual objects, like brains and books. Bryant quotes Harman as saying that there is an absolute difference between real and sensual objects, which strikes me as an odd way to put it, odd but leading, since it expresses the sensual reality of imaginary objects. They exist in and for the senses.

Bryant's view, on the principle there is no difference which does not make a difference, sidesteps the ontological condition of imaginary objects, the question of whether they exist or not, in favour of what they do—and are doing—in the world. Imaginary objects make a difference in the world, but isn't this only to claim for them real effects? Bryant would probably give to difference the ontological status reserved by physics and Cartesian philosophy for causes. The differences made by imaginary objects in and on the world are themselves differences. Harman's view is of objects, imaginary and sensual ones, being in, thus having no independence from, real existing ones. Bryant's is of imaginary and real objects being differences and differences beings: Being is difference, but on the condition of n - 1. Difference makes the difference to Being that it opens Being to differing, being different, from itself.

The impossible is the possible minus being. Is this the divergence Bryant notes between his and Harman's views on imaginary beings? For Harman they are impossible and only by participating in Being can they be accounted for, but not as objects. Only as beings are they possible. Is there a difference then between beings and objects?

Bryant tends to confine himself to beings, that is to subjects—and not objects of which we might claim that they are ever identical to themselves? Deleuze however has it that objects differ from themselves, they have actual and virtual parts, as well as subjects; they are both, subjects and objects, without the modifying condition of self-identity, n - 1. Bryant's beings differ from themselves differently. Whereas Harman's objects differ from being-in-itself for being in a being, in a certain attribute of a being, a sensual attribute, being belongs to Bryant's beings in the form of actual-virtual, and therefore real, difference.

Bryant's imaginary beings are (real) agents of (actual-virtual) difference. Harman's imaginary objects exist in actual perception in the way actual perceptions produce imagined forms or, as it can also be put, virtual images. They also produce them in themselves in the way Bryant's beings produce differences. For Bergson both are images, beings, or actors however are special images for being centres of action.

They perceive themselves to be centres of action but any one of their actions at once comprises that perception. Comprising here is holding and prolonging action in the same way we might say an action contains a movement. While that movement is free it belongs to the zone of nondetermination between perception and taking it into your body as a part of your duration, to be a movement which you are suspended from. You are in suspense.

the image of the flicker – and Loren Eiseley

The image of the flicker I have been using for the virtual form comes from Loren Eiseley:

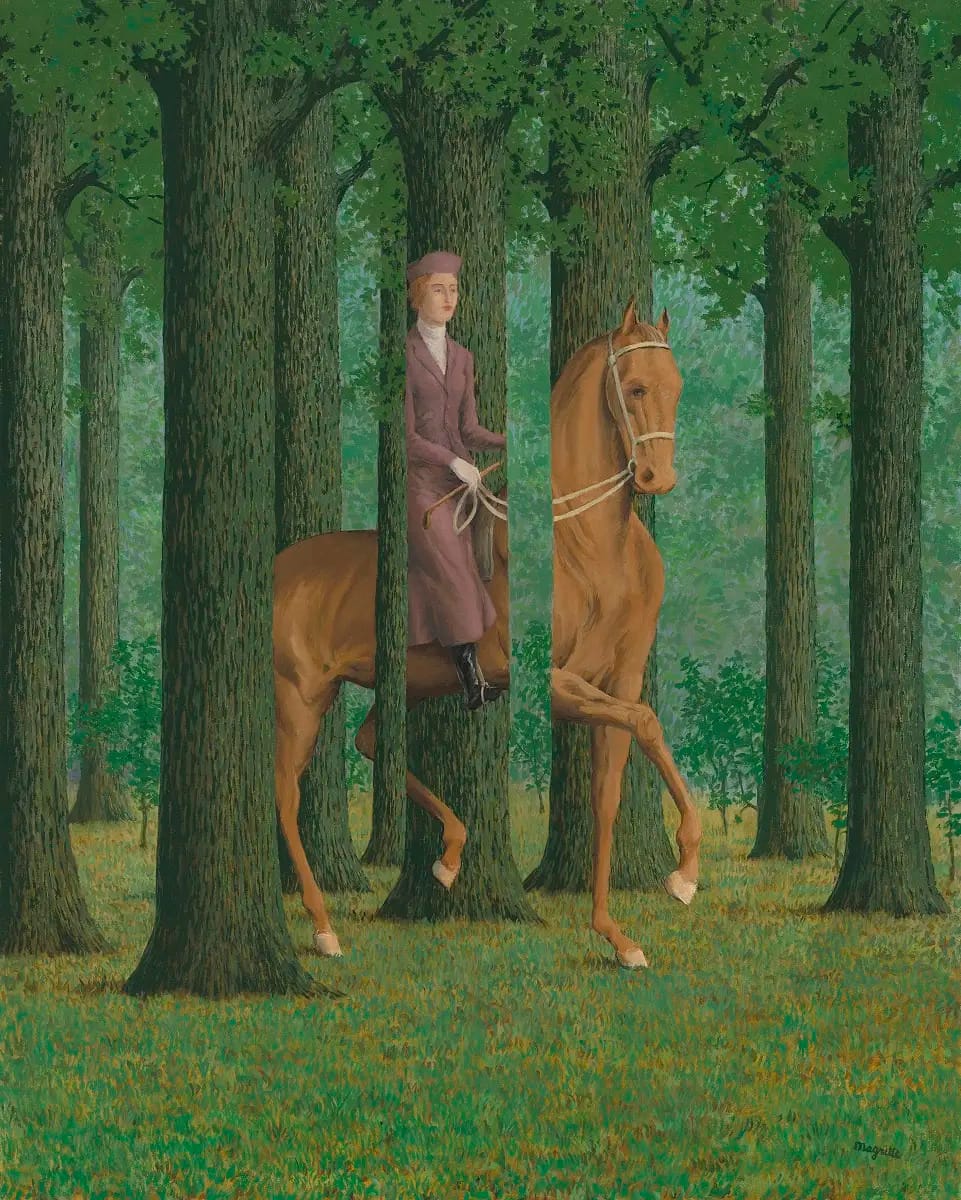

I had been dimly aware that something beyond the reach of my headlights, but at times momentarily caught in their flicker, was accompanying me.

Whatever the creature might be, it was amazingly fleet. I never really saw its true outline. It seemed, at times, to my weary and much-rubbed eyes, to be running upright like a man, or, again, its color appeared to shift in a multiform illusion.

This "multiform illusion" would be meaning.

Sometimes it seemed to be bounding forward. Sometimes it seemed to present a face to me and dance backward. From weary consciousness of an animal I grew slowly aware that the being caught momentarily in my flickering headlights was as much a shapeshifter as the wolf in a folk tale. It was not an animal; ...

It was an animal, it was a man, it was a wolf that was a shapeshifter. It was not an animal.

it was a gliding, leaping mythology.

Yes! a mythology.

I felt the skin crawl on the back of my neck, for this was still the forest of the windigo and the floating heads commemorated so vividly in the masks of the Iroquois. I was lost, but I understood the forest. The blood that ran in me was not urban. I almost said not human. It had come from other times and a far place.

I slowed the car and silently fought to contain the horror that even animals feel before the disruption of the natural order.

Species try and conserve themselves and endure. In a way the human animal has internalised, and preserves and prolongs in the endurance of culture, diverse cultures.

But was there a natural order?

Yes, is there? of a space outside species and individuals?

As I coaxed my lights to a fuller blaze I suddenly realised the absurdity of the question. Why should life tremble before the unexpected if it had not already anticipated the answer? There was no order.

A mythology, a world without order, a mythology to keep it at bay. Now none.

Or, better, what order there might be was far wilder and more formidable than that conjured up by human effort.

Nature has not the scruples we have of conserving in our culture our own mythologies. Its wild onrush is the wild and formidable acts of its imagination, whereas we, urban or not, are more conservative.

It did not help in the least to make out finally that ...

– Loren Eiseley, The Unexpected Universe, published 1964, my copy 1994, p. 202

... the creature who had assigned himself to me was an absurdly spotted dog of dubious affinities—

How brilliant! to be haunted out the side of the mind and of the eye by an absurdly spotted dog of dubious affinities—and what are these affinities but those which we carry in our imagination?

nor did it help that his coat had the curious properties generally attributable to a magician. For how, after all, could I assert with surety what shape this dog had originally possessed a half mile down the road? There was no way of securing his word for it.

And so, meaning again—

The dog was, in actuality, ...

...as actualised in yet another imagined form.

an illusory succession of forms, but momentarily, frozen ...

Frozen in the flicker.

... into the shape "dog" by me. A word, no more. But as it turned away into the night how was I to know it would remain "dog"? By experience?

The test of experience which is what Bryant and Harman are wrestling with above.

No, it had been picked by me out of a running weave of colors and faces into which it would lapse once more as it bounded silently into the inhuman, unpopulated wood.

Now the philosophical part:

We deceive ourselves if we think our self-drawn categories exist there.

Yes, there is the outside with which perception is concerned and to which it belongs. These associations are the children of experience.

The dog would simply become once more an endless running series of forms, which would not, the instant I might vanish, any longer know themselves as "dog."

Once more, the meaning: the series would not know itself. . . When I might vanish.

By a mental effort peculiar to man, I had wrenched a leaping phantom into the flesh "dog," but the shape could not be held, neither his nor my own. We were contradictions and unreal. A nerve net and the lens of an eye had created us.

For Bergson, this is the zone of nondetermination occupied by consciousness. And therefore free will.

Like the dog, I was destined to leap away into the unknown wood. My flesh, my own seemingly unique individuality, was already slipping like flying mist, ...

I am the flicker, that is, the virtual form I carry in my body and that I hold in my mind. These meet again mythologically, that is imaginatively, in the spirit.

... like the colors of the dog, away from the little parcel of my bones. If there was order in us, it was the order of change. I started the car again, but I drove on chastened and unsure. Somewhere something was running and changing in the ...

His double, of dubious affinities to the flesh, bones, the culture and the wood.

– Ibid., p. 203

... haunted wood. I knew no more than that. In a similar way, my mind was leaping and also changing as it sped.

We are as unlikely to capture its meaning as an absurdly spotted dog in the flicker of the headlights.

That was how the true miracle, my own miracle, came to me in its own time and fashion.

There begins 3. of this chapter titled "The Innocent Fox."

Now, to produced a meaning from this virtual form, the flicker, it is out of association with me and goes to my experience, leaps before it like this, a thought:

- the woods, the forest Eiseley drives through, where once the Iroquois were, is an emotional world, an emotional atmosphere, or simply an emotion. The wood is there, and emotion is the space it takes up, because when we read this text, a world in which such things can occur, by the individual gestures of its words, their meanings, and Eiseley's sentences, cannot help but be conjured. It takes place or is the space in which the flicker takes place.

- emotion in this way might define space, but as a mood, here of the forest, the wood. And that we are driving through it gives it extension. The woods extend uncertainly before us and behind us. For Eiseley there is also a depth here—

- which we can equate with his singular psychology, as one who is not urban and who might even say he is not human. From the depth derives the gravity of what the run of the text captures.

- It takes place in memory and would be all memory, strong and moody, affirming and disaffirming, were it not for the flicker of headlights on something that once faces Eiseley and which he makes the product of his own absurdity, an absurdly coloured dog.

- What can we say about its colours? Now the dog, the imagined form, the imaginary being, settles in its form, its colours continue to shift—and even pulsate. Because ...

- ... if nothing else we can say it is alive.

To summarise, for the benefit of Minus Theatre, the play of meanings, of the meanings which define the virtual object in its form, as dog or Eiseley as man, is not projected into or onto the space. The fear and horror there is no order and no categories subsist for understanding develop in the mood of a certain emotional world, one where the gesture can occur, with which it concurs—but it doesn't agree with this world, it produces it; and so it is like a perception. Loren Eiseley names it his. This is important, because then his own boundaries as human become porous, as if they might vanish and he with them. Or that they become porous brings into his mind the thought he must vanish. Yet the flickering form of his imagination continues. Where? Better to ask, wherein? Neither in him nor in the world of the emotion but in the energy, the imaginative energy the dog-man-shapeshifter gesture possesses.

The gesture does not designate the emotional world, it is in a space that opens to it. Yes, its meanings can shift. They are not defined by the space. An actor never thinks with a gesture less than a world.

And we have to come back from words like emotion, space, gesture and time, to the gravity of what has depth. This is important—for you. Otherwise these are empty words, empty gestures. Only then can we return to ask,

—what has meaning for you? Now,

—as soon as the gesture is made, we are not in memory

—the gesture does not suffice the gravity it has, it merely

—interrupts it. Causes a rupture which is that of the interval.

—And so the space opens up around it, with its mood, in which word I am recalling Mark Jackson's lecture on mood at AUT, which he had given, it was said, many times to first-year students in Spatial Design, the department he established. He asked what moods the students had brought in to the lecture theatre. Perhaps one was bored or another had fallen in love and was anxious to get back to their lover. His point was not only that these moods determined how they experienced the lecture but how they changed being there. They defined the spatial state of the lecture + lecture theatre + lecturer + the sounds emanating from his mouth, which had for the students more or less meaning. Either the words were part of the space and agreed over all with that mood or they broke into it, and overcame the mood, were the hinge on which it overturned.

The thought I wished to encounter here was that of how an imaginary object like the ones we use in Minus instead of props and scenery, everything is mimed or sort of half-mimed, the object flickers around the gesture which doesn't contain or capture it, of how it can change. This can't be a matter of You see a dog. I see a man. Of opinion or viewpoint.

Neither can it, although Jeff raised it in the workshop 1 as a matter of imagination, be simply a matter of imagination. Rather it's like the change where Eiseley and the dog change places, when I said, this is important, it is his dog. His dog he knows is absurd. It carries on however and he might vanish.

There is an exchange in the imaginary object between the actor in whose gesture it changes. More than stealing, which thief as a form of theatre is based on, the actor gets behind another meaning. In other words, the stolen gesture is not immediately mine. Before it becomes mine it changes. The noose around my neck becomes your hairdresser showing you the length at which your hair will be cut.

I have been asking after the energy of the gesture, when this is on the outside. Something has to change in the imaginary object, the imaginary object in the emotional world, the mood of the scene, so that it gets taken up in a new mood. So—just take the gesture, and find out where it goes from the time you saw it to the moment you acted it. This is the instant you might vanish ... like the colors of the dog, from the little parcel of your bones.

Should you come back into possession of your body the gesture will have become yours.

the flicker does not yet mean anything

meaning lies in association >> mood of a space