*mpty w*rds by Mario Levrero, minor lit bits

November 25, 1990

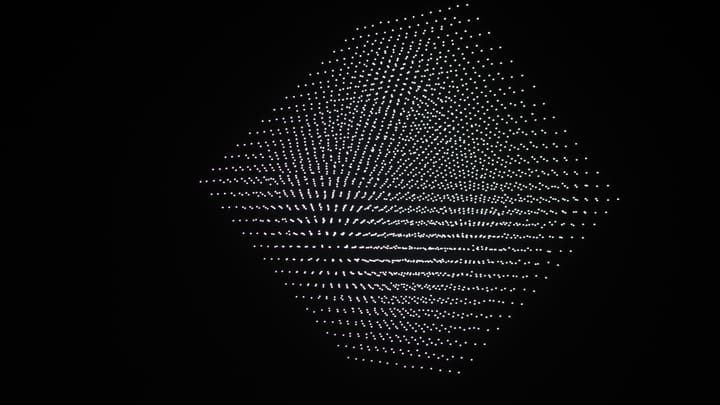

There's a flow, a rhythm, a seemingly empty form; the discourse could end up addressing any topic, image, or idea. This indifference makes me suspicious. I suspect there are all kinds of things—too many—lurking behind the apparent emptiness. I've never found emptiness particularly frightening; sometimes it's even been a place of refuge. What I find frightening is not being able to escape this rhythm, this form that flows onward without revealing its contents. That's why I've decided to write this, beginning with the form, with the flow itself, and introducing the problem of emptiness as subject matter. I hope that this way I'll gradually discover the real subject matter, which for now is disguised as emptiness.

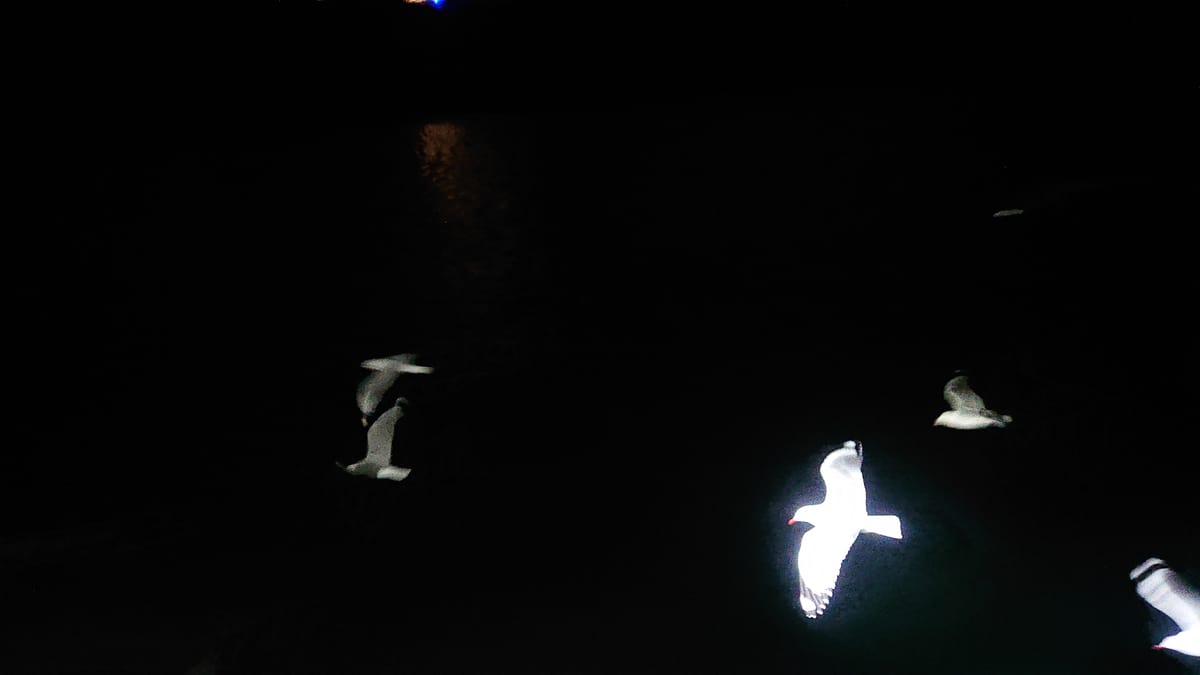

I don't want to force things with images from the past or explanations of the present, which always sound false. I'd rather let the form itself speak, so it reveals its contents bit by bit of its own accord. However, I can't reveal that I'm waiting for it to give something away, because that would send it slipping straight back into apparent emptiness again. I need to be alert [which I copying the words misread as alien] but with my eyes half-closed, as if I were thinking about something else entirely and had no interest in the discourse taking shape. It's like climbing into a fish tank and waiting for the waters to settle and the fish to forget [this is reminding me of David Lynch] they had ever been disturbed, so they move closer, their curiosity drawing them toward me and toward the surface of the tank. Then I'll be able to see them—and perhaps even catch one [for Lynch, an idea].

– Mario Levrero, Empty Words, translated by Annie McDermott, 2019, pp. 29–30

—I stopped writing this. I'd already noticed, a few years before, that this kind of writing has uncontrollable magical effects, and I can't escape a powerful, superstitious feeling of awe and trepidation whenever I do it, as if I were stealing fire from the gods.

There are other kinds of writing, let's call them literary, which have never had this "magical" power for me. What I refer to as my inspired writing, for example, was something I did compulsively [Levrero elsewhere talks about a period of his childhood when he was bedridden and had to get used to living in his head]; it came ready-made from the inner depths. But when I try to address what people call reality, when my writing becomes current and biographical, I can't help unconsciously bringing these mysterious hidden mechanisms into motion. Then they begin to interact secretly, or so it seems, with various visible effects.

– Ibid., pp. 68–69

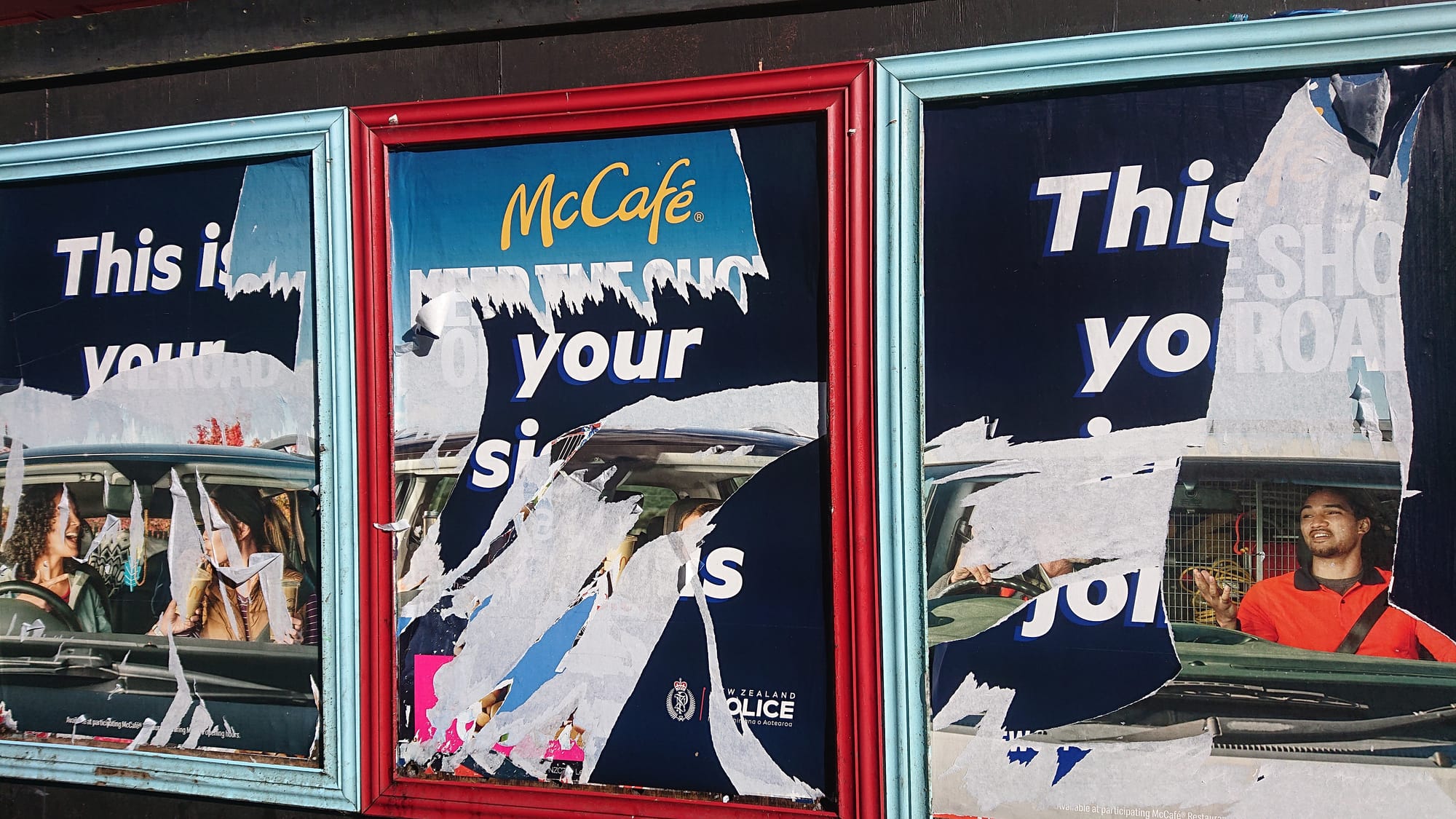

People think, almost unanimously, that what interests me is writing. But what really interests me is remembering. In some languages, the word "remember" comes from the old word for awaken, and that's how I like to think of it. I forget whether it relates to the word for heart as well [in Spanish, recordando, which seems to have the Latin for hinge in it, as I recall here, but obviously doesn't, as Latin for hinge, with no relation to the Greek root of cardiac, is cardo], but I hope it does. After all, remembering things sometimes means knowing them by heart [might Levrero be thinking of cor, which is at the core of both record, recordar, and the Spanish for heart, corazón, leading the former more literally to mean to bring back to heart, to return to the heart as to the mind? Of course he is and I'm quite wrong with the earlier interpolation].

Often people even say: "There's a plot for one of your novels," as if I went around in search of plots for novels and not in search of myself. If I write it's in order to remember, to awaken my sleeping soul, to stir up my mind and discover its secret pathways. Most of my stories are fragments of my soul's memory, not inventions.

The soul has its own way of seeing things. It contains elements of our waking lives, but also elements that are particular and personal to it; the soul is part of a higher order of universal understanding that our consciousness can't access directly. The soul's conception of what happens in and around us, then, is much more complete than anything the narrow, limited self could ever perceive.

Today all those different kinds of ruins came back to me, and I knew it was my soul's way of saying, "I am those ruins." My semi-erotic contemplation of the ruins is really a narcissistic contemplation of myself. And although it comes at a price, and despite the sadness of what's being contemplated, it feels good. When I look at myself in the mirror and see someone I don't like, I think: at least it's someone I can trust. The same thing happens with this inner contemplation. It doesn't matter if I'm looking at an ugly picture as long as it's authentic.

Of course, I don't know to what extent my soul is really mine. It's more that I belong to this soul, which is not, as more than one philosopher has said, necessarily even inside me. It's simply something I don't know about, and the self is only a part—shaped by a certain practical awareness—of a vast ocean that transcends me and in no way belongs to me, a specimen that has emerged, or is emerging, from an immense sea of nucleic acid. But what's behind it, and what impulse is expressing itself by means of the acid? That desire, that curiosity, that greed latent in the material particles.

I'm not interested in finding answers anymore, not in the slightest. For now the questions are enough, and maybe I don't even need them. The discourse [that Levrero calls an empty discourse] has taken this form today precisely because of the things I lack, because for a few moments I glimpsed those fragments of memory, of the soul's memory, and for a few moments I remembered myself. Meanwhile the rest of my life, outside those moments, grows ever more insubstantial.

– Ibid., pp. 85–86

The whole thing feels like I'm hurling myself vertiginously downward through days, weeks, months, and years that pass without a trace, completely empty of content, toward death, the only certainty.

– Ibid., p. 94