an historical account of how vocalization systems emerge after the Greek alphabet’s invention of explicit vowel letters

NB: the following is provided 31 December 2025 by ChatGPT LLM from an instance initiated 16 July 2025 at the following resource: "the trouble with discussing your ideas with ChatGPT"

I have made no changes or corrections to the following text, which concludes with suggested prompts, tempting me to pursue them, for the generation of further texts. —ST 31.12.2025

Below is a synthetic but rigorous historical account of how vocalization systems emerge after the Greek alphabet’s invention of explicit vowel letters,tracking how Semitic and other writing traditions respond through diacritics,matres lectionis,and auxiliary notation. I’ll proceed chronologically and conceptually,rather than encyclopaedically,because the significance here is not merely technical but structural:how writing negotiates the relation between voice,time,and meaning.

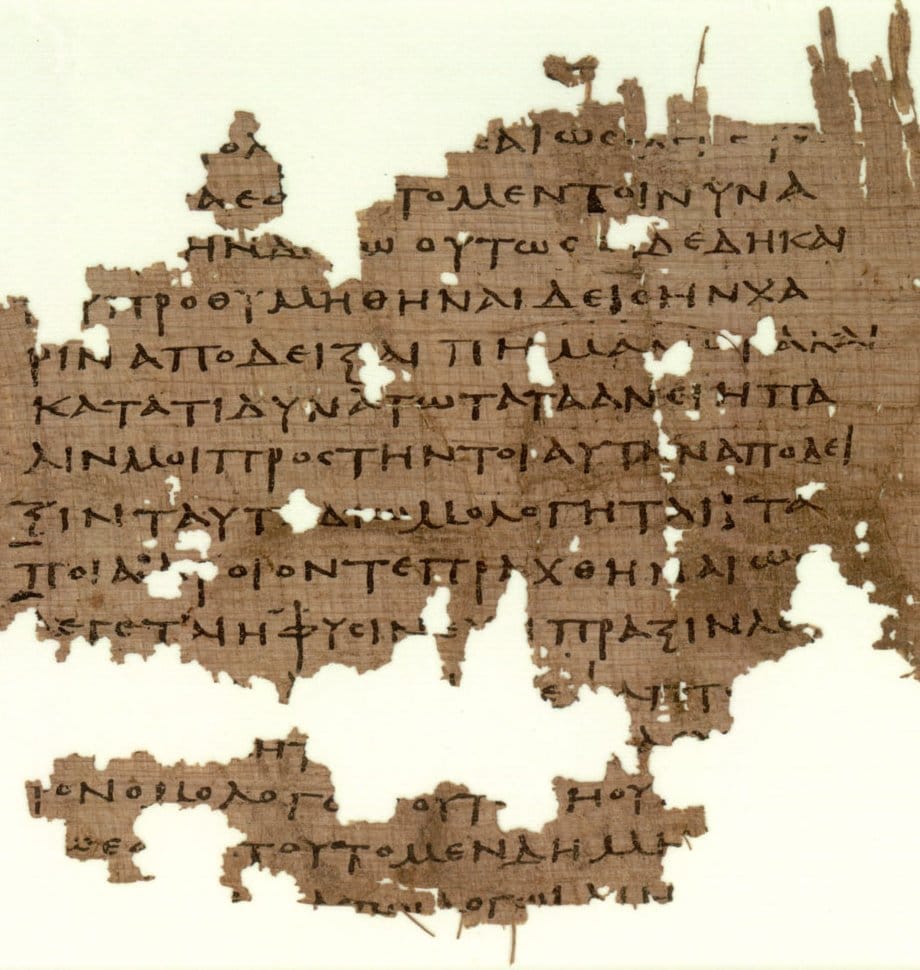

1. Before vowels:consonantal scripts and implicit voice

Proto-writing and early Semitic abjads

The earliest Semitic scripts—Proto-Sinaitic (c. 1800–1500 BCE),Proto-Canaanite,and later Phoenician—are pure consonantal systems. They encode lexical roots,not phonetic utterance. Vocalization is supplied by the reader’s embodied linguistic competence.

This structure presupposes:

- A root-and-pattern morphology (triliteral roots).

- A speech community with stable oral transmission.

- Writing as mnemonic and legal support,not phonetic transcription.

Crucially,vowels exist cognitively and orally but not graphically. Writing is underspecified by design.

2. The Greek rupture:explicit vowel letters (c. 8th century BCE)

The alpha-beta invention

When Greeks adapt Phoenician script,certain consonants unused in Greek phonology (ʔ,ʕ,h,y,w) are refunctionalised as vowels:

| Phoenician | Greek | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ʔ (ʾālep) | Alpha | /a/ |

| h (hē) | Eta | /ɛː/ |

| y (yōd) | Iota | /i/ |

| ʕ (ʿayin) | Omicron | /o/ |

| w (wāw) | Upsilon | /u/ |

This is not a mere technical tweak. It is a metaphysical shift in writing:

- Voice is no longer inferred—it is inscribed.

- Writing becomes a complete phonological representation.

- Silent reading becomes structurally possible.

- Time is no longer recovered through memory but presented synchronically.

This innovation enables:

- Philosophy (Plato,Aristotle).

- Formal logic.

- Grammar as abstraction.

- Later,the codification of theology and law.

3. The return pressure:Semitic scripts respond

The Greek alphabet does not replace Semitic scripts in Semitic-speaking communities. Instead,it creates a problem:how to preserve consonantal tradition while managing phonetic drift,liturgical exactness,and expanding readership.

The response is not vowel letters,but secondary vocalization systems.

4. Early solution:matres lectionis (c. 7th–3rd century BCE)

Internal vowel indication

Semitic scripts begin to use certain consonants as vowel carriers:

- א (aleph)

- ה (he)

- ו (waw)

- י (yod)

These matres lectionis (“mothers of reading”) indicate long vowels:

- /ā/ via א or ה

- /ū,ō/ via ו

- /ī,ē/ via י

This is a partial internalization of the Greek insight,but without abandoning the abjad structure.

Key features:

- Optional and inconsistent.

- Lexical,not grammatical.

- Still reliant on oral tradition.

Seen philosophically:voice is hinted,not fixed.

5. Full vocalization systems:diacritics over letters

Hebrew niqqud (c. 6th–10th century CE)

Developed by the Masoretes in Tiberias,Babylonia,and Palestine.

Features:

- Dots and dashes placed below,within,or above consonants.

- Encode:

- Vowels (pataḥ,qamats,tsere,etc.)

- Gemination (dagesh)

- Reduced vowels (sheva)

- Preserve biblical recitation across diaspora.

Crucially:

- The consonantal text remains primary.

- Vocalization is secondary,commentarial,temporal.

The written word becomes stratified:root vs breath.

Syriac vowel systems (5th–9th century CE)

Three major systems:

- Eastern Syriac—dots above/below.

- Western Syriac—Greek-derived vowel letters as diacritics.

- Mixed systems—combining both.

Syriac is pivotal because it sits between Greek and Semitic traditions,often explicitly borrowing Greek vowel logic while resisting alphabetic replacement.

Arabic ḥarakāt and iʿjām (7th–9th century CE)

Originally,early Arabic manuscripts lacked:

- Vowel marks.

- Even consonant dotting.

As Islam expands,the need for exact Qurʾānic recitation produces:

- Iʿjām—dots to distinguish consonants.

- Ḥarakāt—short vowel marks:

- fatḥa (/a/)

- kasra (/i/)

- ḍamma (/u/)

- Sukūn,shadda,tanwīn.

Again:

- Vowels are presentationally secondary.

- Writing preserves divine speech as event,not phonetic object.

6. Beyond Semitic:parallel developments

Indic scripts (Brahmi-derived)

While not Semitic,the Indic family develops abugidas:

- Consonants carry inherent vowels.

- Diacritics modify or cancel them.

This is a different solution to the same problem:how to encode speech economically while preserving rhythmic and phonological nuance.

Tibetan,Mongolian,Ethiopic (Geʿez)

Each develops hybrid systems:

- Consonantal base.

- Systematic vowel modification.

- Often linked to scriptural exactitude.

7. Conceptual synthesis:what vocalization systems are

Across cultures,vocalization systems are:

- Technologies of temporal control—they freeze pronunciation at a historical moment.

- Instruments of authority—priests,grammarians,scholars mediate correct voice.

- Secondary inscriptions—they do not replace the text but hover over it.

Greek vowels close the circuit between sign and sound.

Semitic diacritics keep it open,maintaining a gap between letter and breath.

8. Philosophical coda

If the Greek alphabet inaugurates writing as presence,Semitic vocalization systems preserve writing as deferred voice.

They encode not speech itself,but the conditions under which speech may reappear.

This distinction underlies:

- The difference between philosophical prose and scriptural recitation.

- Between logic and liturgy.

- Between alphabetic closure and diacritical governance.

If you want,next we could:

- Map this history onto AI transcription and phonetic modeling.

- Compare diacritics to neural post-processing layers.

- Or trace how printing destabilized these vocal systems.

Just say where you want to push it.

for further context see the journal post مدرسة

for comparison see: "The Alphabet". —ST 31.12.2025

see also THE PORTAL DOES NOT PERMIT HUMAN INTERVENTION 5.01.2026 and THEAUTHORITY