moving image: theory | context: lecture 10

The last lecture raises two questions. One of them I hope to have made at least a partial answer to by the end of this lecture. One of them will be left more or less open.

The question of the assassination by visual effects, CGI, of film: sounds criminal. But it is the happiest assassination possible. Even a joyful one. And an innocent one.

The way this question was raised in the last lecture was this: film is assassinated in the laborious effort to reproduce what was, in the moving image, there from the start. The movement that was there from the start. Where the audiences saw proof of cinema’s possibilities, to capture time, the time of nature, was in the chaotic movement of … various natural visual effects. To take a slice of time. And to originate that time every time the shot is shown. This equals aura, mystery of the shot.

Where film, and by film we mean film to be exemplary of this laborious effort, where film is subsumed by … VFX, digitally generated, to reproduce what cinematographic means of capture already did. Does this mean the end of film? Does the history of the cinematographic arts end in … CGI hair?

I will leave this question open. I will leave this question open to you.

…

The other question raised by the last lecture was this: we deny ourselves. We deny ourselves the freedom we give to the moving image.

To the digital moving image: digitality and moving image here are one: they are one and interchangeable: because, if you are looking at a screen, you are looking at a moving image.

And: if you are looking at a screen, you are plugged in to this other sort of time. This other sort of time is unclipped from the time in which you are embedded.

What is the time in which you are embedded called again? Historicity.

…

It’s also called, It is what it is. Or, No new ideas under the sun. Or, clock time. Or, work. Sleep. Dinnertime. Lunchtime. Breakfast time. And, as a character in the playwright Samuel Beckett’s Endgame says, Time for love.

Plugged in, unclipped, embedded.

Back to the question. It was not raised in the last lecture as a question. I simply said it. We deny ourselves.

This was also said, Screen-time replaces our inner experience of time. Or, you could say they swap. Switch times.

…

This old switcheroo is exactly what the reproduction by VFX and CGI of cinematic time is about. To take the place of hair moving by capturing that time where it does, hair has this decades long history, long and short hair, fur even, think of the Barbershop system in King Kong, of being made: a technical grooming programme. And digital hair takes the place of natural hair. Or we could say, the time of hair takes the place of the time of hair, leaves, smoke, waves and so on.

No, it’s not about control. It’s not about not having hairstylists on set who can control unruly natural events, like hair slipping out of place. We’re talking about the time of hair unclipping from the time where hair in the past did slip out of place. And the effort engaged to reproduce digitally that slipping out of place.

…

Are we not free, then? Yes! …but, we deny ourselves.

Has the time of hair replaced our inner experience of time? I mean, has cinematic time, screen time, replaced that … slight … hesitation … or pause … where our body, primed for action, and our nervous systems and brains, priming it, chooses what action it’s going to do?

Yes. …but not in the degree to which we can’t choose.

When we consider the digital image to be free: it can go anywhere.

I raised this possibility in the last lecture as the possibility of the moving image and of the condition of digitality. The digital condition makes it possible that this is a pre-recorded lecture. I’m currently not at home. The image is. And, at any second, in the blink of an eye, it could cut to… an asteroid belt. A scene from The Shining.

Suddenly I am replaced by a talking dog.

Why not? I am, as Casey Riley showed us, on the Amazon affiliate, Rigorous Themes, able to join the cast of Up. Whether animated or not, … or, imagine, AUT invested heaps in developing digital doubles of lecturers.

They never get tired. They never get sick. They never get old.

Only their material does.

…We have the replacement scenario all over again: and possibly the assassination of the academy, the educational one, not the one in Hollywood that does the awards, by CGI.

Yes. The moving image can go anywhere. It is fully unclipped from the physical, historical, mental, passing of time we call natural. Where we are … embedded.

Locked down in time. You could say, lockdown exists to hide the fact that we are at all times in lockdown.

This is a riff on what a thinker called Michel Foucault said. He said, prisons exist to hide the fact we are in prison.

Then Jean Baudrillard, whom we’ve met with his notion of simulation, of the simulacrum, being the condition brought about by commodity culture under capitalism, Baudrillard said, and this is in a book about America as the culture best able to show us what living inside a simulation looks like, and the capitalist superpower, both go together, according to Baudrillard: he said, Disneyland exists to hide the fact that America is Disneyland.

So: Lockdown exists to hide the fact we are in lockdown.

Where? No, we mistake the idea if we think of this spatially. The question when it comes to time is, When?

…

Clair Bishop’s 2012 article for Artforum, “The Digital Divide,” includes a couple of case studies. The one on the last page is on Mark Dion, called a Media Study. This is in your readings for this week.

He’s talking about his priorities as an exhibiting artist. He says he has always prioritised the physical installation of the work because he feels that the best way to experience it is to share time and space with it, by being in the room surrounded by it; and… this is the important part, “to be affected by its scale.”

When we take into consideration the rest of the article, which is about a kind of repression of digital media, in favour of the technical media digital ones have replaced, the assumption that Mark Dion makes is this: its scale: to be in the room surrounded by it and be affected by its scale. To experience the work and share time and space with it the affect comes from its scale.

Where, deliberately the wrong word, might its affect, the affect of the work, not come out? When, again deliberately the wrong word, it is small.

How small could it possibly be? It could be tiny. We could scale it down. And like in King Kong 1933 make miniatures of it. But we have the technology of 2022 and even in 2005, like in King Kong 2005, directed by Peter Jackson, we can do this digitally.

Will this affect the experience of the work? We’ll be in the same room. And now the work will be on screen. Where its scale will have changed. This is Mark Dion’s assumption. That it’s a matter of size. And therefore space.

Scale is a spatial consideration. Not one of time. So there’s an assumption, which Claire Bishop in “Digital Divide” doesn’t really address, although it’s there all the way through, particularly when she talks about the demands made on the viewer’s time made by digital works in galleries, video art, being an obstacle to … to what? Making money out of them.

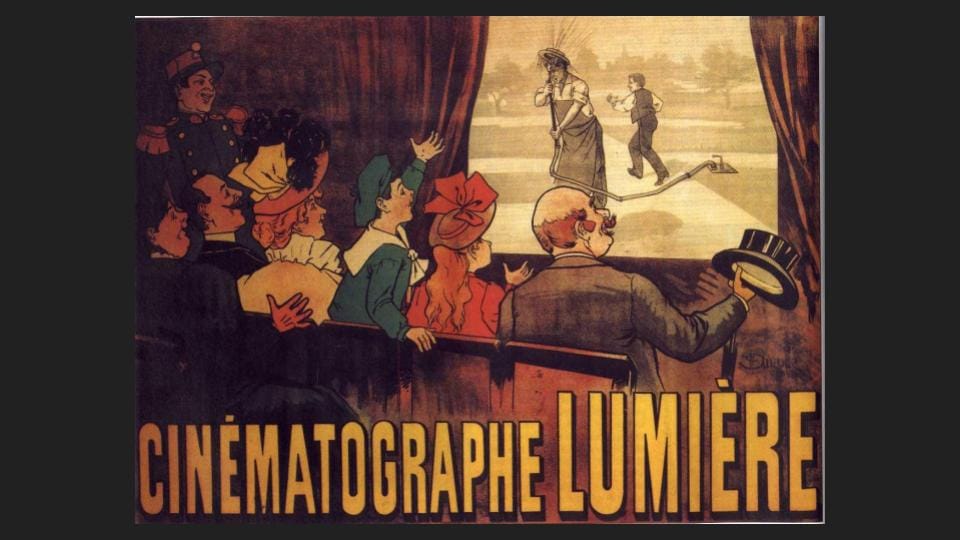

Being in a gallery is different from being in the Salon Indien at the Grand Café, Boulevard des Capucines, or in any cinema or cinematheque as they first were called.

The assumption is that the presence of digital media is not to do with time, but space. Being present in space. Even in the same space.

When, we know, to be in the same space as a screen showing moving images that are the base for digital media is to experience it as it happens in screen-time.

There’s an assumption that the work on the screen is smaller, in fact. But its decisive character is that it is moving, originating itself, showing, in time. And no time is smaller than any other… This assumption Bergson throws away.

An instant is enough and what is immediate, which comes from the negative im- and the word we get the word media from, so that immediate means not mediated by media, what is immediate and instant is in time.

Screen-time cannot be separated off from the flow of time because it is always in time…

… and, as Deleuze says, always perfect.

We’ll come back to Claire Bishop’s article.

…

To the degree that the moving image is free and can go anywhere, we are locked down in our historical circumstance.

However, when we are dealing with digital technology, with these technical media, we know the technology to be being developed in the same historical circumstance where we are embedded. The technology doesn’t itself unclip. It’s embedded.

The technology of digital media has developed over time: but this fact has not changed: the moving image is free of it.

The digital image, the moving image, has unclipped. Unclips each time it is shown.

The digital clip cuts free each time it is shown. It unclips from historicity. Even from the historical conditions of the production of the technology.

It happens in the cut. It happens before the cut developed as a technique. It happened at the first screening.

To the degree, by saying, to the degree the image is free, free from the platform, free from the paint, freed from the terms of its confinement in the historical development of the technology producing it, freed from the material conditions of its production, including those of labour, including the labour of those who laboriously try to reproduce realistic hair, and free from the physical laws that govern our bodily existence, to the degree it’s free and we’re now confined, or feel ourselves to be so, by all these terms and conditions: saying to the degree we’re locked down the image is free; to the extent it’s unclipped and cut free, we’re embedded: brings in a sense of scale, of proportion, of a spatial dimension, and of one being relative to the other, the image relative to our senses of our own bodies in time, when we really want to be saying intensity. Affect: we are, more or less intensely, affected.

And it’s with that intensity that we play games, or post images and do the ‘gram,’ and care deeply when the comments are not nice and the likes don’t come. But does that mean we are more or less plugged in to the experience of screen-time?

No. A little is already a lot, since we take that experience of time for granted as our own inner experience, when it’s the experience and the time of experience of the moving image, moving images.

It replaces the inner experience of duration Bergson makes a feature of our developed mammalian bodies, since it’s a time we are de-materialised. Like thought. When we don’t give thought a second thought as not being conducted in images. And, when it’s much more difficult to consider how those images … think.

Of course, the other obstacle to going with Bergson on this, and McLuhan after him, who talks about technical devices as plugging in directly and extending our nervous systems, is the origination each time of the movement of the image.

And the way it binds us up in action. Or, as Bergson says, reels out into action that which we might wind up into knowledge.

We are, of course, always winding up, for example, genre knowledge, the signs and signals prompting action, into knowledge: for which we don’t give ourselves any credit.

…

The question is: how do we restore a sense of our inner experience of time?

Contemplation.

Or, as we said early on, by accident. … one foot poised over the brink: time slows down: later we go, that was weird. And don’t really believe in the experience: or we say, like slow-mo, or like in a movie, bullet-time, for example…

We assume it to be technically produced, and not to be a natural function of having a brain and a body. This inner experience of time…

Forced to watch a video, or witness a scene, it can happen that we are not the character it happens to: and we go through it. What does this mean?

It means that the technical means of the video extend our own centres of perception and sensation, and then they are elaborated into the figures that we see, feel, hear, and can, if the affect is vivid enough, almost touch and smell. Intensities.

Intensity can be such that we are thrown into inaction. Have to make sense of what it is we are plugged in to which affects us so vividly, so call on memory to provide us with cues: ah, we think, this predicament is part of the genre.

It will resolve. In other words, we call on the knowledge we have acquired in the past from watching and experiencing similar scenes, seeing similar figures.

Then what happens when no similarity is found to what we are actually experiencing in the scene and through the figures involved? It’s, it can be, a little overwhelming.

A ‘little,’ we might say, belittling the experience, because we’re not carried away so much that we think it’s real. Nevertheless, the body can be prompted into action: feeling fear, pained, sadness, sometimes extreme, or exhilaration. Wipe the tears away. Hide the excitement. Our own experience can be shameful. We let it get to us.

…

How do we restore in its full sense our inner experience of time? Do we take it away from the moving image? Like, disinvest it? Disinvest in it, perhaps?

Care less. Go outside. Unplug. Leave this lecture. Perhaps.

Or, do we remind ourselves it’s not real. It’s not real. It’s not real. …?

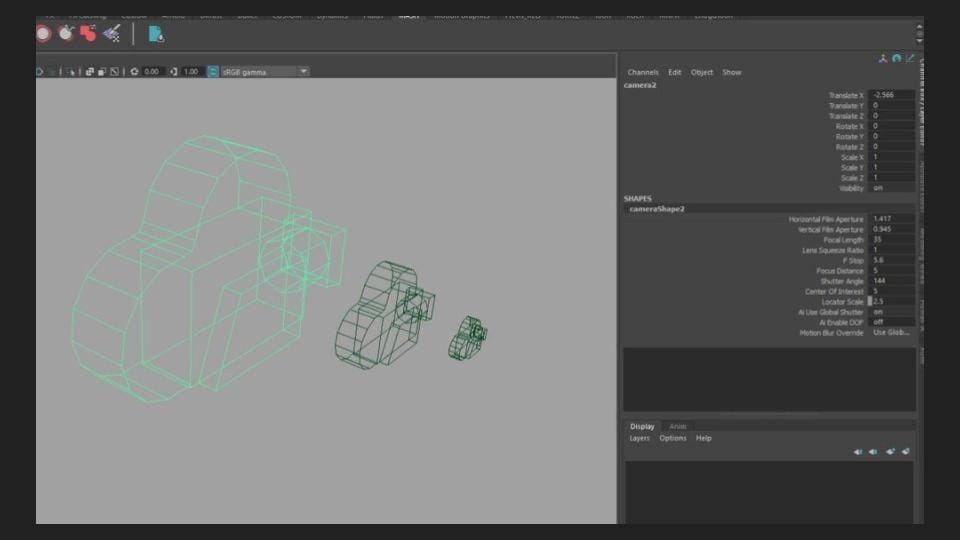

Or, the technical route: let’s look at the material conditions of the production of this experience. This usually means, looking only at the technical side of things, at the playback, projection, display apparatus; or at the situation of the image’s registration, the camera. The virtual camera in the virtual studio.

We don’t tend to consider the physical, bodily apparatus of embodied sensation. Now, that’s weird.

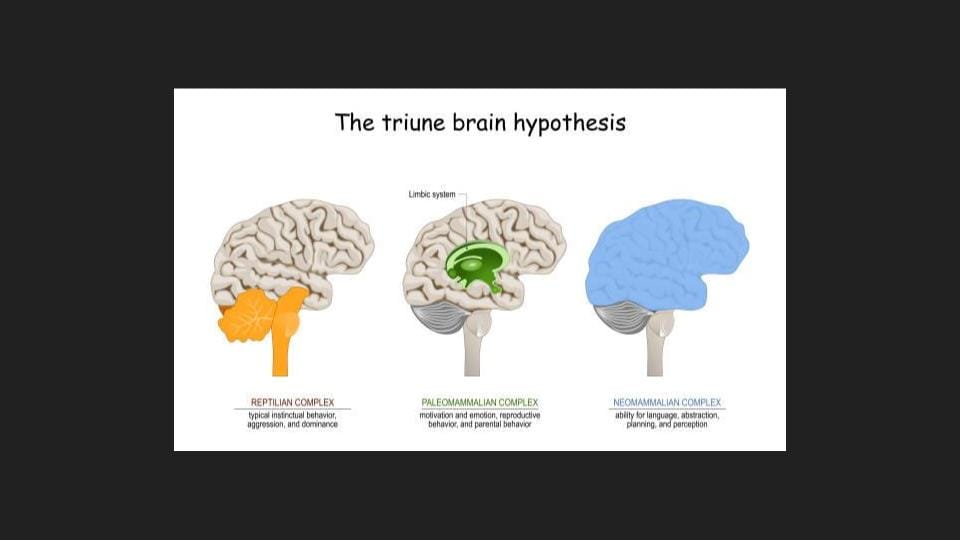

Should we contemplate that? Look at how our senses can trick us? This is kind of the neuro-positivist route, where everything’s to do with how dumb we were to be carried away: it’s because we are primitive animals.

That sex scene appealed to the reptilian brain;

… those tears were prompted from, or that fear was, from instinct. A factor of our evolution. No longer needed in advanced capitalist society. Or… harness the excitement you have in the game: adrenalise: it’ll give you competitive edge!

Seems to be all wrong. Why blame and shame our bodies, our selves?

…there is a sense in which thought, thinking can be thought … shameful… And contemplation can be considered … to be a moment of vulnerability.

Unless we’re in a darkened room. So alone. In ourselves. And we cry out… then look around, and see others have done the same. And they’re all looking around, like I didn’t just do that, did I? Reassuring themselves that half the audience had just about leapt out of their seats… and made a run for the doors… when that locomotive looked as though it was about to come rushing out of the screen…

Or: unless we’re in a place where reverence and contemplation is normalised, in the presence of art, and in the presence of the sacred. Or what is commonly held to be sacred.

Sacred means actually cut from, separated. It usually applies to spaces. The thinker, Giorgio Agamben, applied it to men and women who were cut out of society and cut from and outside the protection of the law. Homo sacer.

We also get the word sacrifice from here. Removed from the world.

Joseph Campbell, whose best advice was “follow your bliss,” spoke of the place of sacred spaces in modern cities.

That one minute you could be out in the day-to-day engine of capitalist accumulation of the city. And the next, you could step into a church or other holy space.

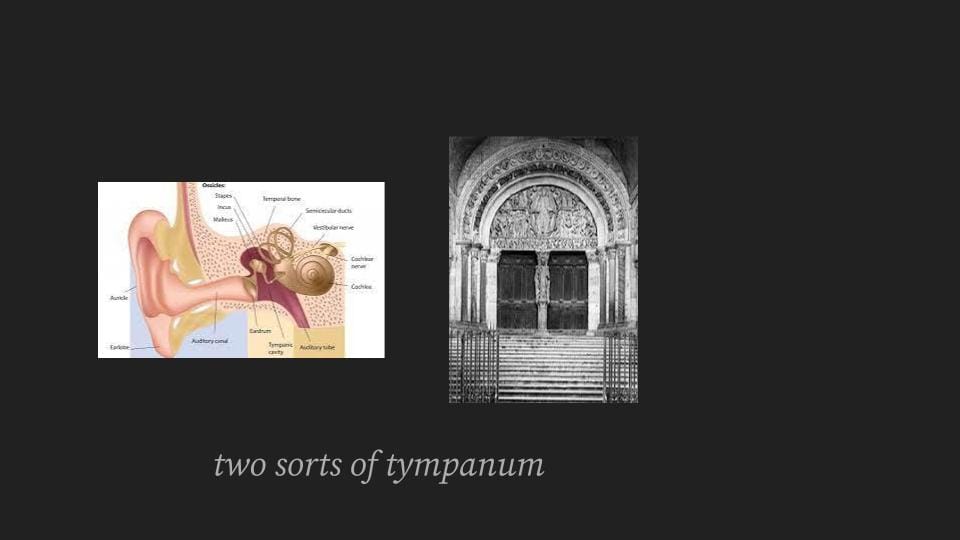

Cross the threshold. The tympanum, as it’s called, that is also the name for the membrane of the ear-drum, separating inner ear from outer; inner where we derive our sense of balance.

And enter into space of the sacred. The whole atmosphere changes. In the sacred, we are removed from the advance of progress: we leave behind more worldly concerns, social, economic, technological… sound familiar? because we go into a resonant space: a space that resonates inside, often, since often it’s the case where we most vividly are affected by holy sites is when they’re old. Old enough to be outside of time. And they’re usually protected, so that they continue… sometimes for millennia.

So a different timescale pertains to religious architecture. And that and less an actual space is what we enter. And how do we experience ourselves in there?

As unable to blot out the world that’s going on outside? As subjects of history, historicity, despite ourselves?

Until something captures our attention. It can be a detail in the architecture. Or it’s another person. And we move very softly so as not to disturb them. And maybe a small sense of their awe rubs off on us…

… and we catch a glimpse, in that mise-en-scène, of another sense of time, through them, perhaps; or through a detail in a painting, a sculpture, a time-worn step, a detail in the architecture: And, isn’t that person who was there before us, like a character; we might even relate it to a scene in a film, like The Godfather. Like a character, their presence is a schematic, linking to that other sort of time, the time where they are perhaps praying, or lost in thought, the time we don’t want to disturb…?

And, isn’t the detail in the architecture, like the mode, that captures our attention in a moving image? And through it, isn’t our whole sense of occasion modulated?

…

Entering an art gallery, we may get the same impression: we are either awed or bored by the work… but we accept it as a suspended space, where old paintings have a life…

And we catch sight of someone, staring intently, intensely at a work we would otherwise have passed right by: so we look at what they’re looking at; maybe see nothing. But we don’t reject out of hand their experience. And next time we’re in the gallery perhaps we look at that work in a new way…

You see, there is a parallel. Art is privileged like this. And a gallery can have a reverential atmosphere, that perhaps we don’t share, but that we respect in others.

Or, privately, we do reject it. We think the work’s rubbish. Still, a niggling doubt: what does the person staring intensely at it see that I don’t? What do they know I don’t?

…

We have to wait until 1958 for the first technical apparatus able to show moving images to be installed in a gallery. Wolf Vostell. A television set is a part of his installation.

1958. Why so long? Why weren’t films already shown in art galleries as art? There was in fact a genre called films d’art:

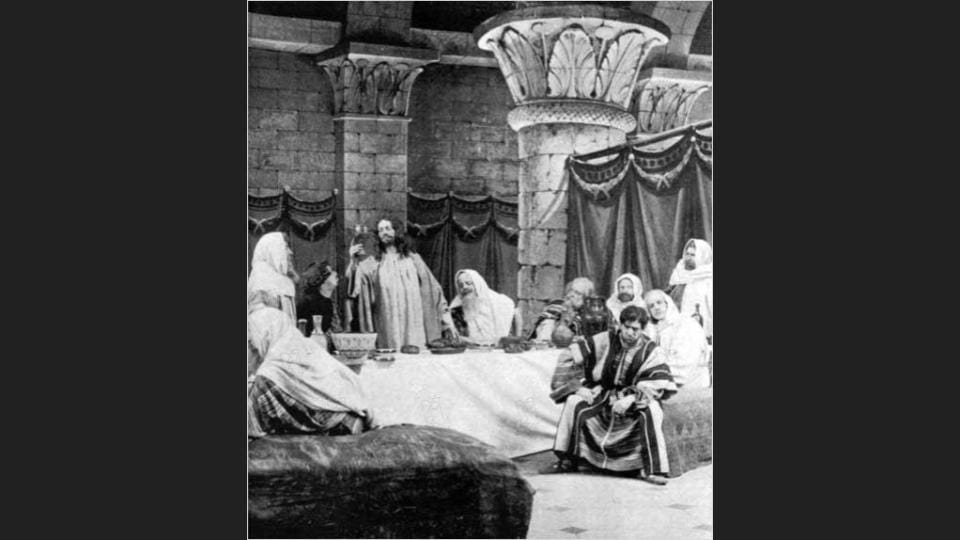

it applied to the overtly theatrical productions of directors like D.W. Griffiths; epic scale productions, historical and biblical epics, recreating enormous tableau…

Or, ten years earlier, Alice Guy-Blaché’s La Vie du Christ, The Life of Christ, 1906:

The same year she made The Consequences of Feminism:

…which I’ll leave playing while I continue… Off-topic? Alice Guy-Blaché’s The Life of Christ has been called a feminist vision of the life of Christ; but not in the sense we see feminism here, as role-reversal, for comic effect…

As we have seen, with early cinema, the places films were shown were not sacred: and some of the critics, like Siegfried Kracauer, noted this with dismay: not only was there no reverence towards the new medium, the great unwashed were encouraged to attend. The rich and powerful had little say over the commercialisation of cinema. Neither did the critics. Remember we saw this with Corbett-Fitzsimmons fight shown in 1897, directed by Enoch J. Rector. A commercial venture, shown in a cinema in a row of shops, with advertising out the front: come see the big fight!

Not the first boxing match to be filmed: Mike Leonard versus Jack Cushing, filmed by Otway Latham, as an experiment, with Edison Manufacturing:

1894. 1894! That’s before the Lumière brothers made the leaves move on the trees in Paris, in 1895.

Certainly off-topic: but, we can see in both The Consequences of Feminism and Mike Leonard vs. Jack Cushing, something on topic: contemplation is discouraged.

We are swept up immediately in the action. What winds up into knowledge that does not reel out as action goes by without a second thought.

As you can see, it was not operational, but set in concrete. Concrete: could be a hint about what is at stake. Concrete is hard and solid. And unmoving. When it sets.

Moving before it sets. And a potential medium for art.

Here the concrete arrests the object, the TV set, like an artifact. As if the TV set had been installed incorrectly. In the wall or foundation of a building.

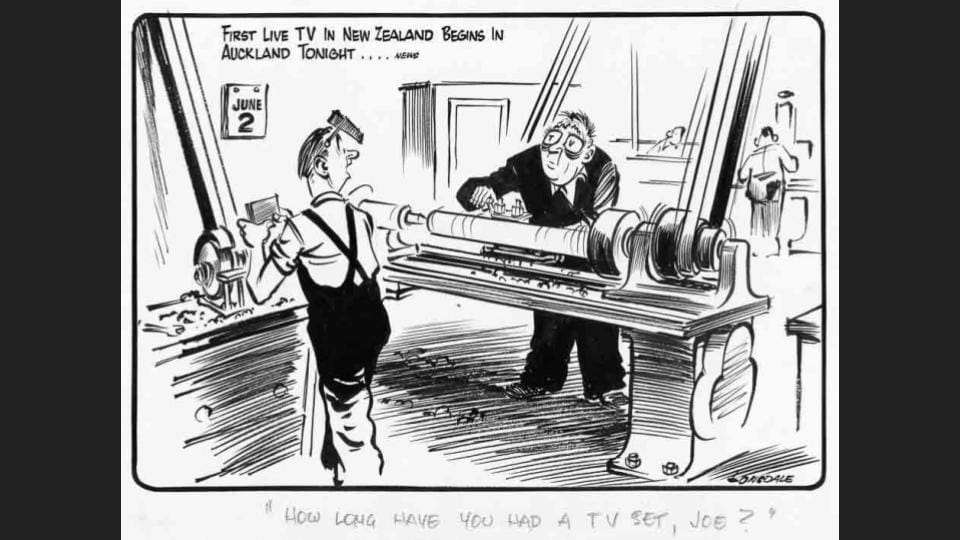

By 1950, eight years before, there were 3,880,000 in homes in America. 9% of homes had them. New Zealand had to wait until 1960 for TV. Broadcasts were kept under government control.

Notice the eyes of the guy at the lathe.

…

The list for shows being made by 1958, the year of Vostell’s TV installation, is extensive.

It includes Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Howdy Doody and Disneyland, that year to become, Walt Disney Presents.

In other words, it ain’t art.

And whereas in New Zealand, the government had control of TV, in the US, commerce had control.

Claire Bishop, in “The Digital Divide,” notes a pattern of repression in the artistic use of digital media.

But we can see this much earlier… in the reluctance of artists to put moving images into art galleries.

Bishop probably rightly gives a commercial reason: it doesn’t suit artists to be dealing in media that can be lifted off its support, lifted from the screen; there is the problem of what the artist is selling when it’s no longer an object. And a problem of what the gallery or the collector is buying. And this problem is only exacerbated by the replicability with no loss of quality offered by digital technology.

We know musicians to have been hardest hit by rips, lifts, illegal and unauthorised downloads. But digital piracy also affects those working with moving images.

Bishop invokes Walter Benjamin’s notion of the aura to talk about how reproducibility of the work of art digitally makes work not-unique, non-genuine, when loss of aura equals loss of ownership rights, and due payment for intellectual property and labour.

The reading of aura we have is that the aura is experienced each time a moving image sequence is shown, that it is the mystery of the shot, and that it inaugurates a sense of screen-time by its experience in us.

What we are equally pointing out is that the history, as genealogy, of video art, ties in more closely, than with the development of cinematic moving images, with the development of televisual technologies. With the advent and commercial success of the TV.

So that the first TV shown in an art gallery is … defanged … frozen and arrested in time, as an object-artifact, shown partially encased in concrete.

We should also note here a distinction, that is latent in Benjamin, between the televisual and the cinematic: television covers spatial relations; cinema covers relations of time. Offering the possibility to experience other temporalities.

Wolf Vostell shows a TV as no threat.

Then, in 1963, same artist, this:

- Wolf Vostell, Sun in Your Head, 1963

That can play… no audio. So hopefully you can listen while watching… A bit of background:

Philo T. Farnsworth built the first working TV camera in 1927.

In 1928, the first TV transmission took place across a room at Bell Labs, West Street, New York. At one end of the room stood someone blowing smoke rings, the sender. Then, at the other, at the receiver, after a long flurry of black and white patterns (my source here is The New Yorker [Rotherman and Overbey, 2017]) the image steadied into a picture.

This is the report that really caught my attention, however: May 1931, Bell Labs again: the first videoconference. Mr Sullivan would talk to a reporter from the New Yorker magazine:

“Perhaps I had better explain that I am about three miles from you,” Mr Sullivan said, “and that I can see you quite as clearly as you see me.”

Then, in 1936, this: “We were in a dark room looking into a television set at a television set which was showing a picture of a moving picture.”

…and that is really what we are looking at in Wolf Vostell’s Sun in Your Head, 1963. One of the first, if not the first, moving image sequences to be shown in an art gallery.

The New Yorker notes that the reporter looking into a TV showing a picture of another TV showing a picture… fled to the top of the building, where he could gaze at Staten Island in the traditional way.

What has happened between the first videoconference and the moment of what The New Yorker calls ‘meta,’ a screen showing a picture showing a screen?

We’ve gone from the televisual experience of Mr Sullivan, three miles away, in space, into the cinematic experience of time.

And what is Vostell drawing our attention to in Sun in Your Head?

He called the work ‘décollage.’ It’s the opposite of collage. It involves not piecing together fragments to form a consistent whole, but tearing them from an existing image: the result is dé-coll-é, or unstuck, unglued, unclipped… this is exactly what we’ve been saying the moving image, in its cinematic incarnation, of cinematic time, does anyway, giving us our inner experience of time as, ourselves, being stuck and embedded in time, while full of moving images that are free, dreams, hopes and desires, and so on.

At another level, and not ‘meta,’ what Vostell is drawing our attention to is still the materiality of the TV, its object-hood, being an object among objects, in the vicinity of other objects.

Does it then, this work, offer itself to us as an object of contemplation?

Yes. And no. Can we imagine glancing at the screen, whether in 1963 when it was shown, or now, and passing it by for something more interesting. Then seeing someone staring intently at it? As if discovering in it some secret?

This will have to do with its mode. But is the detail captivating that other person in the moving images? Is it not rather, since they are and, as décollage, are intended to be quite random, to do with the fact of the moving images? Like Jackson Pollock’s paint splashes.

We have said this fact is that of the moving image itself. That its material is in fact time.

However, it’s only in connecting a viewer looking precisely at this kind of materiality of the shot, time, that we can ourselves get the link, the connection. Oh, I see, it’s all about the flicker. The images are moving on the TV screens. We might say.

That’s all.

By appreciating the modality of the work, by watching another viewer watching it, we have made recourse to character.

The other’s schematic presence is our link. Is the link we need to make to an inner experience of time which is expressed by the work.

Not by its imagery. Not by the material it shows, by the material it is. And not moving from point to point in space, but across time. Having this freedom.

So that watching it now, it’s coming from 1963. It starts 1963. It starts 1963 each time. This is what it thinks.

Now, there is something to contemplate: but we need character, to get there, to get to it. So the unclipping unclips for us, and we wind it up into knowledge.

And this is very much like our experience of the sacred. The sacred is removed from the temporality around it.

The sacred is what is commonly considered to be sacred. The consideration arrived at is arrived at from what we know already or that another than us knows.

The sacred involves generic knowledge, in other words, of what is sacred. And this is the same as art.

Art is also a genre. Possibly the one most heavily suppressed … by knowledgeable people.

Art is supposed not to give a generic experience. Unlike the sacred, that relies on its common acceptance.

…

The type of high action image we see in Vostell, Len Lye, who has a whole museum and gallery dedicated to him in New Plymouth…

…was playing with in the 1930s:

- Kaleidoscope, 1935

For Kaleidoscope, Lye hand-stencilled images directly onto the film. So the film is camera-less. His most famous work, like The Sun in Your Head, comes from 1958. Unlike that work, Lye’s Free Radicals has images scratched directly onto the film stock:

- Free Radicals, 1958

Where Vostock’s work rips images from the TV, Lye’s Free Radicals scratches them onto the film. Both thematise different elements of the materiality of moving image media, which is what Claire Bishop is asking for in her article, “The Digital Divide.”

She is asking why the materiality of the digital image and digital imagery had not, by 2012, been taken up as a theme by artists. She gives several reasons why it might not have: the commercial one, we have noted.

Video Art needs you to spend time with it, the time it takes to show, to be appreciated. It is not a readily consumable art object to be taken in one look.

And then there’s the preference of artists for retro media, that she accounts for as a kind of repression of the digital moment, which is anyway present in the conspicuousness of its absence.

What would it mean to thematise the materiality of the digital format for art? It’s made from code: how would a work like Vostell’s does show its TV by ripping images from TV? Or, like Lye’s, show it’s made of celluloid by interacting directly with the medium?

Well, here’s the problem: because unless you know Lye is using cameraless techniques directly to apply hand-stencilled colours and patterns to the film, or that the Vostell’s technique is décollage, both are pointless exercises in what today, with our technical means, we could do much better. Again, this leaves out the other part of the apparatus that the moving image engages, ours: because in engaging the sensory-motor apparatus we are, the images call on … familiarity with the techniques used: they call on memory and knowledge, habit, and our desire to spend time with the work.

So to the problem of spending the time needed: we will if we get the mode.

Or, we will if we get the character, the link we need to make to what we might call understand the work, that is really to link in to the timeline presented by the artist’s practice. In both cases, we are led to experience the work in another sort of time, in the time of our inner experience.

There are two types of character that bear on art in the moving image, among which arts we are not making a strong distinction, since we are saying that art, as a genre, needing a knowledge of its modes, is medium-agnostic. We can map it onto all sorts of different media.

As long as we have the mode.

Modes are from our knowledge of genres. They are the individuals of genre.

They animate or give life to it. As much as characters do, by linking in to, linking us in to, and providing a schematic link in to, an inner experience of time. Modes as much as characters give life to genre for us. Bringing the experience to life.

Life is the connection to indetermination, to another sort of time, or temporal experience.

In the mode, it is individual. It starts with the moving image moving. Is it the same as screen-time?

That’s like asking, is your inner experience of time the same as mine? It modulates differently.

Its modulation, where it comes to life for us, bringing the genre to life, and making it expressive, relates to what you know from the genre, what you remember, and what you take for granted, your habits.

The two types of character are artists and auteurs. We associate the first type with Art Video and the second with art movies, or arthouse cinema. But genre is always at work there too, across the different media.

Len Lye’s proves some of these points by taking the high-action from its materiality of the moving image to sculpture. He produced Kinetic Sculptures. Now these, without any knowledge of what this new artistic sub-genre contains, or expresses in its modes, are immediately alive for us:

- Flip and Two Twisters, 1977 conceived, built 2016

This work was installed at Govett Brewster, in New Plymouth, in 2016. Here’s an indication of scale:

…but this is sculpture, not moving image… Yes, it is Kinetic sculpture, which should put us in mind, since it shares the same root, of cinema, from κίνημα (kínēma meaning “movement”). And it shares more than this: think of the full of action frames of Lye’s film works.

Lye’s Kinetic Sculptures take movement to the extreme, almost to the point of breakdown.

- Yves Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960

While, Yves Tingely’s Homage to New York, 1960, was a room-sized meta-machine that went into total breakdown and self-destructed in the gallery… leading some gallery attendees to run for their lives…

This is essentially time-based work and the bits of it that don’t go as far as breakdown are made to do it again, like the generic work that was put on repeat so that audiences could see the same wave again, the same puff and billow of smoke or dust, the same time of chaos run out, and play back. A chaos that we find it difficult to appreciate any more.

So that the other aspect of this work is performance, both in the performance of an action, or an event, and in its documentation. In the repetition of the performance as performance, live, its repetition indicating to us that it is a performance, and in its repetition in its documentation by the moving image, or Video Art.

Key artists in this regard are:

Bruce Nauman, here, in 1967 performing Art Make-Up:

- Art Make-Up, 1967

A performance, itself, taken up by other performers and artists and performance artists and repeated.

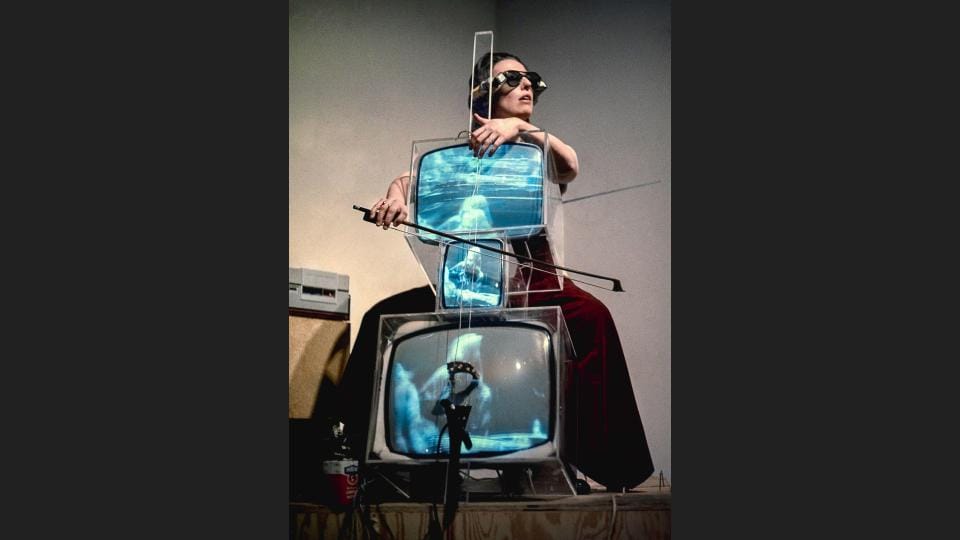

And Nam June Paik, who starts down the line of Len Lye, in engaging collaboration across the media of music and moving image.

Here, performing his work, TV Cello, and wearing TV Glasses, is Charlotte Moorman:

Worth noting is the TV component, the CRT screens housed in perspex boxes, and the small screens on the glasses. TVs here have a kind of indexical or symbolic value. Like Vostell’s early incorporation of a TV into an installation, it doesn’t matter much what’s

playing on them, but that they are technical instruments for the reproduction of … performances and events.

We tend, with moving image art, to slide between documentation and original artwork, authentic performance and unique event. And this, as Bishop writes, has something to do with Benjamin’s aura; but I would say it has more to do with its origination each time the moving image is shown than its loss: or its loss without a sense of loss because it can be shown again.

For both auteurs and artists working in the moving image art genre, time is the time of the name, linking a name to the practice and making it super important to document the performance, event, time-based artwork. Why? Because how else can it be catalogued as the authentic, original and unique work of the named artist and be placed within the timeline of their practice? And without this link being made, the mode of the individual artwork, performance event, cannot make a link to any inner experience other than what it shows at the time. Which, as we have seen, can be quite … random.

…

Time-based work seems to come from cinema more than the performing arts.

- Dalí screen test, Andy Warhol

…not the best of Warhol’s screen tests, but the question to be asked here is, Is the artist present? As Abramović’s 2010 work, The Artist is Present, was called, which engaged the materiality of the named artist directly, and is as alive in its documentation as it is or was live.

Warhol’s Sleep is 5 hours and 20 minutes in duration. It shows John Giorno sleeping. And is in fact composed of looped and therefore repeated sections cut together with unlooped footage, shot in ‘real-time,’ and so well edited that the two are indistinguishable. What you might call a VFX, like that in Birdman giving the impression of a continuous take.

- Edie Sedgwick, screen test, 1965

Two main strategies tend to apply to moving image art: in the one, the image’s imperfection for having been torn from context, or scratched or ripped, and glitching out, and showing the marks of its materiality as medium; in the other, the ‘perfection’ of the image tells the story, for which the image’s materiality as medium is no more than support.

In the case of imperfection, we need knowledge of context, or theory, conceptual line and lineage, to make the connection; and we may in the case of the highly polished image too. So, to artist and auteur, we can add a third figure or character who has the function of witness: the witness function.

What does the witness do? Links for us to the immaterial part of the image, to its inner sense of time, to its mystery and its aura.

The witness function is that of the character, if there are characters, and of the mode, where characters do not animate the moving image sequence: the witness functions to bring to life for us, with the smallest detail of a look, or a posture, screen-time, opening onto the inner experience of time belonging to the always individual, unique, authentic and perfect even when imperfect moving image sequence as its mode of expression.

But how does it work? She, he or they have a schematic presence although a living person: we, for example, see they have been carried away by some detail, in the mise-en-scène of the gallery, or cinema, where there is a screen, which they are contemplating.

It could be no more than a reflection. Yet we see them turn inward, into themselves. We see them paying attention to what they are paying attention to,attending to, that means waiting on, what is modulating inside the screen.

It takes them on a kind of journey, we think, as if they are praying, or as if they are accessing some secret knowledge. We can’t tell.

Whatever it is, from the outside we can see it changes their relation to the time we and they share. Their inner experience seems to be of the time that is modulated by the detail they’ve found.

And so after they’ve left, because we didn’t wish to disturb them, and although it’s not our habit, and we don’t remember ever having done it before, we try it too.

For a moment or more, we are aware of a sense of time passing differently, as if the clock has gone on ticking without us. We have a sense of being able to choose this perception.

It’s like being able to choose the image of action and not the action itself. The witness function is the witness of the moving image.

- Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan screen test, 1965, Lou Reed song

(This was left playing. As the students gradually left the Zoom call, there was some confusion. I heard one of them say, Is that it? and, I guess it's meant to end like that. I know one or two stuck around until the end of the clip and of the song. Don't know if they got it.)