molecular communism

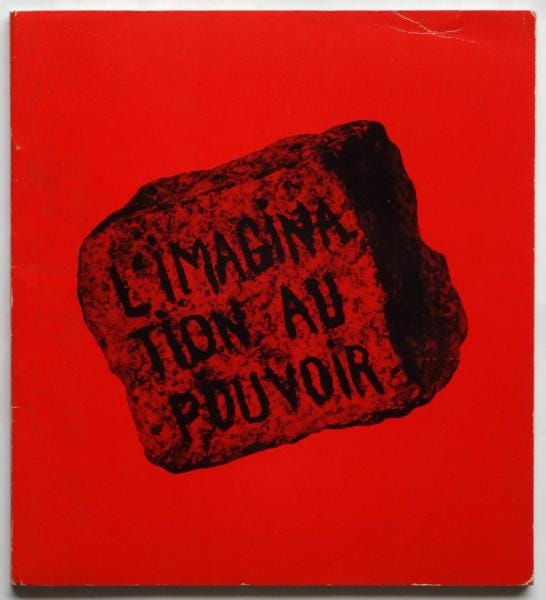

Gareth Simpson, having replied to What Is A Practice? with some great questions, is my interlocutor here. A question put to me by Johannes Birringer in an email (he can let me know whether he minds my using his proper name and I can remove it later) has also prompted me to return to themes discussed there, of which AI is not the least. I would like, while still trying to be as direct as possible, to start with the image I have chosen and the title of this post.

I have two sources in mind. The first is one that eluded me when I tried to cite it in a post which really went off the rails, here. It is a reference to Gustaw Herling (Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, 20 May 1919 - 4 July 2000), whose Volcano and Miracle, a selection of fiction and nonfiction from his "Journal Written at Night," contains the observation that those with hope did not survive the camps, in his case the Soviet labour camps. He did.

Without hope, then: the second source is Richard Gilman-Opalsky in discussion about his book Imaginary Power, Real Horizons on the podcast Acid Horizon (available here). It's subtitled The Practicality of Utopianism, its subject—imagination. It has moreover to do with the practice of imagination, which I think brings together both Herling's book and this one.

Gilman-Opalsky says that the imagination is under attack. This is what the attack on the humanities and liberal arts amounts to in universities all over the world. It is a confession by the ruling classes of their fear, their almost pathological fear of the imagination, a fear inspiring hatred and violence against the imagination, leading to what has been called in Gaza scholasticide which is the close companion of genocide.

When we hear it as a confession we may also be hearing what must be defended. To Herling's finding that those in the camps who had hope did not survive can be added, those who had imagination, dreams did. Gilman-Opalsky talks about a sociologist friend of his who in conversations with children in the former Palestine when asked what they most wanted said that they wanted their dreams back. Dreams here equate not with hope but with imagination.

Molecular communism: a long meandering question is put to Gilman-Opalsky about the final inescapability of capitalism and least of all through the molar practice of communism, which led to many like Herling being pressed into forced labour. His answer is that what is best in capitalism is unable to be reduced to capital. Not finally, as the disproportionate force and violence of the attack on the imagination shows.

What is best is love, friendship and dreams and other works of the imagination that don't so much inspire hope as engage practices, those practices of which they are the outcome. Dreams, love, friendship and other works of the imagination not only result from the imagination but are the proof of its practicality. And why so much effort is expended on its eradication, by force and by financialisation, which is that cooptation by capitalism, under neoliberalism more than ever, making cultural goods too expensive to have, humanities' departments too expensive to run and humanity generally impossible.

Without stating it in terms of molecular communism this is the work Gilman-Opalsky is suggesting can be done, and that he affirms as his life's work. Alongside the most devastating forms of financial capitalism we have a communism which is already here. It is minoritarian, molecular, is always escaping, escaping even those forces which incite to its expression so as to re-appropriate it to capital, chief among which is the financialisation of data: this is the public good AI serves.

Gareth asks after, in some final statements of the earlier post, what I say is the "story of moving from critique to affirmation," in his words:

One thing I am curious about, and maybe the answer is in there... you said "The change in my process comes at about the same time as that at which I begin this post, with the question that shocked me out of a kind of critical daze. Or maze. It is the story of moving from critique to affirmation. What do you choose for? What is your practice? process? thought? such that you would choose for it again, each time." What was it that brought this question to you now, at this moment in your life? Is it the first time you've asked yourself that, or simply that first time that this question had this impact/effect/affect? What is the 'biography' of the shock? And of the outcome? why that outcome now?

The biography of the shock would be a wonderful title. There is a long now in question here, the now of Stephen Zeppke's challenge, really, to answer on behalf of practice-led research, for the claim of an imaginative practice that it can in itself be research and stand up to academic scrutiny and examination. From Stephen's own biography comes his disbelief that it can. And the now of the time I am writing, that post from June 25, when I was in Stephen's position, invited to act as external examiner but for an MA rather than a PhD, and beginning this, July 1 2025, finishing it two weeks later.

I believe on the contrary that a practice, in the arts as in other disciplines, can in itself be research. However there is the factor of the written component to consider. For practice-based research it is secondary.

It is an exegesis and follows, exegetically, the practical work, without embellishment, and ideally, although this is open to contention, without interpretation. Most of the problems arise here and can be summed up in one word—justification. My first experience of university, it was half-way through the year and I had to have permission from the course leaders to enter.

My ticket in was that I was on good terms with members of the German department. I had learnt German, my father was already in West Germany on a DAAD (German exchange programme) and, at year's end, the family were going to be joining him in Munich (where he was in fact learning the language as well). I needed more points, credits, however, to make the thing worthwhile (university was free in those days, fees paid and there was an allowance I could claim as well). Since it was offering a half-year course I was interested in, I approached the philosophy department.

I knocked on the door of the head of department at Victoria. I imagine it was the old building, brick, gothic, where the office was. I must have received some sort of reply because I entered and said, intending to excuse my interruption, "Sorry..." but the head of department, barely looking up, cut me off:

"Who are you?" I told him.

"There's no need to apologise for existing, Taylor" he said. As we have inherited it from the Middle Ages (I say this because there is a nasty little graph doing the rounds on social media purporting to show there was no 'scientific' advancement then, for a thousand years, and implying this was due to Christianity), scholastic work is supposed to entail reading and writing. It is here that most who practice imaginative work will seek to justify themselves, in both.

In reading, we can show off how much we've read, and, if the professor or academic mentor has read Heidegger or Sartre, show that we have too. The student, whose MA work I was marking, had written an exegesis thick with citation. Writing, we can construct the fiction that our work is important, necessary and relevant because—so and so, whose work we have read, encourages us to think so.

We can expect a PhD candidate to have closely read texts they profess to know and an MA student to have nearly read them. I had been reading certain authors from when I'd written my MA thesis in 1990. A conventional thesis, it came out of the shock of reading literary theory for the first time—in a course convened, so it seemed doing it, with the intention of deconstructing us instead of any texts, literary or otherwise, outside of it.

I took these authors up, and circulated them amongst the other students, as weapons against that class: they were the antidote to too radical a destabilisation (many of my fellow students had fallen into depression or quit the class). Nihilism, Cosmetics and Audacity, the title of my thesis (available here), had to be submitted for external examination because my supervisor, and the convenor of the course in Literary Theory, marked it down. K.K. Ruthven, its external examiner, said in his examiner's report I ought to be encouraged to carry on to a PhD, which I did 23 years later.

I thank him. I had, however, as my first supervisor put it, a long time in the wilderness, but I came to my PhD having read closely those authors, was well-armed and prepared to defend, not perhaps my existential condition, my academic conditions at least. Something jumped out at me from the texts my MA examinee had nearly read. It was a claim being used to support a practice in Chinese phantasmagoria that these date back in the West to the 18th century, which is true, they do but the student was also emphatic about the cultural hybridity of their practice, bridging East and West; now Chinese phantasmagoria, for which there is the word 幻景 (huànjǐng) date back to the same period, even using magic lanterns (for which there is also the word 幻灯, huàndēng). This tradition was ignored: and the movement towards the new was claimed to be in the use of modern Western digital technology; this too has a history, perhaps not in phantasmagoria, in art installations, equally as long in the East. In this case the academic apparatus, however well or improperly put together (in contravention, in its use of AI to find sources, of the ethical disclosure demanded by the institution), was in contradiction with the central claims made in practice and in the exegesis.

Medieval scholasticism invents in the use of language a critical organ of perception. This is the academic apparatus, and its use of language may be called technical. There are all the technicalities of citation to observe and of the support for statements by reference to authorities, who appear in the bibliography. But calling it technical and an apparatus reduces to convention and habit what is most interesting and imaginative about academic practice: that it perceives new things.

Scholasticism as mode of perception

It puts books to work on books, texts on texts—hence the emphasis on citation, correct citation being as necessary as a correct procedure is in surgery—to discover secret and hidden meanings. Turning up the secret and hidden sides of words and of discourse it doesn't seek to disenchant.

The enchantment of relying on absolute authority and being confined to it is one of the charges brought against the Middle and Dark Ages, when in practice scholastic work was, exactly what we know of practice-based research, exegetical. Rather, the myth of disenchantment, its history dating back to the same period as Chinese and European phantasmagoria, is a myth about the birth of modern science, that it frees us to see clearly, with the cost that it disenchants the world. And the magical book of nature can no longer be followed but with the technical apparatus—the tools and instruments—of science.

The myth is imposed, the nostalgia for an enchanted earth with it, which is actually felt, mainly at Jena by poet-philosophers in the period science is born (note that that generation in Europe were nostalgic not for the enchantment of the Renaissance but of Classical Antiquity), to convince that the observed world, to the exclusion of all others, is real and true, concrete and solid, until the evidence shows otherwise. Natural philosophers, like Hooke and Boyle, based their findings on observation; yes, but see what happens: observations, of which members of England's Royal Society were exegetes, have to be organised.

The evidence so far has not only to be organised but also collated and collected—hence the archive. Not only this, new evidence has to join it. Joining it is not however the same job as the research finding it: holding it up against the evidence collected in the archive, to see whether it is new and challenges the old, is a scholastic, that is to say an academic practice. So is the additional work of publishing findings.

Scientific papers, articles, journals and books are as bound to the critical organ of citation as biblical exegetes, but in a way that scientific authorities are seen as functions of the visions they convey, not visionaries themselves. Their authority comes from the vision which they serve. It is a vision and seen as not singular to them. That is apart from by those outside the field, for whom Einstein is a genius, Oppenheimer is a genius, and Steve Jobs and Elon Musk are visionaries.

All this places both arts and humanities, as well as human and social sciences, in a double bind: a disenchanted world will not abide what does not have the authority of science; science will not admit of supporting itself on medieval practices, practices from the Dark Ages. Unless, that is, it is accepted that knowledge is only ever an organised field of associations that does as well for dreams as for science.

Knowledge is only ever an organised field of associations that does as well for dreams as for science.

The rediscovery that this is the case, of the power of the archive which is the inheritance of scholasticism, comes about with Nietzsche, not a trained philosopher, a scholar of texts, a philologist.

In all the efforts to re-enchant the world, or to scientise, to turn fields as diverse as economics and sociology, English, linguistics, psychotherapy and political philosophy into sciences, Nietzsche uncovers a lie, a nihilism that, as these efforts are ongoing, is self-destructive. He doesn't pit academicism against, as they had become, the human sciences, Geisteswissenschaften in German. This is the other charge brought, the stultification of scholarship in the early academy, where not only dogma reigned and biblical authority was absolute and could not be questioned but also where exegesis and hermeneutical practice as a result became like a prison and could only, while laying palimpsest on palimpsest, turn in a circle. It was like communism where no individual voice could be heard but repetition held in an iron vice. He ran headlong into it, which is why at the heart of his writing you could almost say he was affirming the self-destroying tendency, that or because it came from self-hatred seeking to purify it. But there's no critical debate or dialectic in Nietzsche—and perhaps because of this the Nazis could read him.

Nietzsche's rediscovery of scholasticism—and I am only dealing with it because it is relevant to reading and writing—didn't bear fruit, perhaps with the exception of Bataille, until after the war and after the redoubled efforts of structuralism to set the human sciences in hard scientific terms. These efforts begin in anthropology and we have a figure in France like Barthes who is an intermediary, who writes structuralism and goes on to mythologies. Then comes Foucault, among others, whom Deleuze calls in his book on him the new archivist.

He practically affirms, after Nietzsche's key move, discursivity: on discourse he practices genealogy; that is, he perceives in it something like a biblical, dogmatic shape, and he doesn't pierce the skin but identifies with precision the textual seeds (Latin, seme, from which semiotics) from which it has grown, the law against vagrancy which led to the carceral society we inhabit, of prisons and asylums, increasingly the same. I should like to say that, where genealogy might be the method, he develops scholasticism as a mode of perception. It goes beyond method since, as in Nietzsche, there is no critical debate or dialectic, only affirmation, like a good book or the Good Book, an affirmation of structural genesis, a shiver that goes over the deep and the word.

And Derrida: dangerous Derrida, whose style—of scholasticism, a mode of perceiving texts like there was nothing else but them and we were all texts and exegetes of ourselves—held its own enchantments for humanities departments in the '80s in the English-speaking world, and led to a generation of copyists, attracted by the danger presented when everything that is is at once the benefactor of its own self-destruction, so to read a text meant to participate in the nihilism Nietzsche identified. I remember, I was doing my MA and visited Auckland, with a view to perhaps continuing my studies, and because I came from an English department I visited the English department at Auckland University. A knock at the door, a swift and friendly "Come in!" but when I said I was interested in literary theory, I was ushered straight out again. We spoke in whispers in the hallway. Theory then posed to some in the department the danger we are now seeing play out, of the downfall of, as Nietzsche might say, old values, but not their replacement by new ones. Derrida develops deconstruction and différance as methods of a scholastic perception—these too have been scientised and called procedures, which they are but only if we keep in mind what they are procedures of.

The strange case of Deleuze (among others), his use of scholasticism, that is to say the academic and critical organ itself, which supported those schools where the humanities arose, from studies in rhetoric, logic, theology and law—and, I should note here I differ from those who think that the crisis in the humanities comes from either a loss of faith (enchantment) or from its critique (disenchantment)—, has three aspects:

- a strain of what Joshua Ramey in his book of 2012 identifies as hermeticism, a close companion of scholasticism, and a feature of faith in things, secret and hidden, which exceed us and our language: that is, the references Ramey maps bear witness to a visionary or transcendental capacity which Deleuze both endorses, in his fondness for the mystic tradition, and of which he is the impartial observer, researcher and experimenter, like an alchemist. He practices empiricism.

- before 1968 and the publication of Difference and Repetition and The Logic of Sense, Deleuze wrote books focused on the philosophical tradition. In them he does something like Foucault. He doesn't adulterate or engage in interpretation—more importantly, he doesn't write critically on authors, but he is precise in his citation and proper towards the bibliographic organ, which, something like in Derrida, in deconstruction, produces works that are fundamentally unfaithful to their sources. They are, he says, monsters.

- Deleuze, taking up on the importance of his eschewal of either dialectic or critique, affirms in his sources what is perceived by his mode of scholasticism. Not a personal style, not a writing style, it is a style of reading. As in the second aspect of his use of scholasticism, as in his academicism, he reads to affirm his sources, sometimes in their style, style of thinking, style of writing, sometimes in the matter of their thinking and the matter of their writing. The difference comes from a division of labour, not between matter and style, between thinking and writing which here correspond to scholasticism, academic work, and philosophy. He reads, as in the first aspect of his practice as a scholar, for mystical undertones, subterranean effusions, smells and tastes, which we can understand as either affect or experience: he reads for transformations that are both magical and natural—natural to language, but not like Derrida, for magical formulas. This should put him beyond the pale of the academy—and we can look to the experiment of Vincennes, razed in 3 days by ministerial decree, for proof. However, we don't know where the division lies in his work because both writing and reading are non-critical, positive and affirmative practices, a mode of philosophical investigation (or perception), a mode of academic pedagogy (or perception).

And here we look to how he teaches for proof. I recently received a delightful gift from Charles Stivale. He sent me On Painting, his translation of Deleuze's seminars, from which came the book on Francis Bacon, its subtitle The Logic of Sensation. He and Nancy came to visit Waiheke Island so that is how the connection arose. I thank him.

I realise I have called these aspects of Deleuze's scholasticism, which run alongside his mode of philosophy, because they have this function too: they offer points of view. To be precise, the affirmative way Deleuze reads offers points of view which are his sources'. They are perceptual modes, literally the perceptions the authors he cites express in their writing. Yet, siding with the philosophical side he calls them conceptual personae.

How do we teach this? How do we teach this as an imaginative and creative use of scholasticism, of producing the scholarly organ, which is for each who reads and writes, as it is for each author it cites, a mode of perception? As it is for the reading list, the discovery and presentation of a literary context for an academic work, and the bibliography?

I have called it in a lecture critical but while each may be said to have their style of speaking, their way of reading, their style of writing, their way of listening—well, badly and so on—what is introduced into reading, writing, listening and speaking, although we might call it a critical organ, is not a critical distance. It does not come about by a kind of suspended attentiveness, in which the act of reading, writing, listening, speaking has a plane put over it or outside of it from which we critically observe both ourselves and the materials, the reading matter, the textual shapes, the sounds, and their physical movements. Rather it is open, affirms it or them, follows the outline, is a point of view and by an act of imagination engages in solving a problem.

As if there were one there! That's where we get the idea of critical thinking: it finds problems where there are none. But to approach the encounter with reading matter, writing material, on each encounter, as if we had to crack its code: to do so we have to adhere to a logic that is nowhere else except in that code. To do so without reproducing it and if we do reproduce the problem it gives us we will just have to solve that problem.

And so on. Deleuze affirms the problem which is singular, a problem, and individuates the solution as well. It could be thought, if we only need affirm it, everything is right with the world. He makes special use of language. In Difference and Repetition he asks what if anything is analysis if not breaking something down into its constituent parts, finding its origin—as in the genealogical method—and, not grafting onto it some new critical addition, by using negation in light of the way it works by addition, making positive that which it would negate, destroying it but only so as to plant something new. This method is Nietzsche's annihilation of nihilism.

I am saying scholasticism names this special use of language. Where the method might differ, genealogy, deconstruction, affirmation (taking critique all the way to the creation of new values), the use of language on language as a mode of perception is consistent. Academic training exists to develop this sense.

We learn and are taught, or not taught, to read and to write again, using the same critical recursivity we would in any practice (or suspending it, under the same conditions of critical recursivity. Karl Ove Knausgård, asked how he wrote My Struggle so quickly, answered that he had to turn off his inner critic; sometimes, he says, as a result I wrote shit. But sometimes life is shit.) The point here of recursivity is a practical one, where we turn back from forging forward and look at the chop we have created as it surges up behind pushing us onward: all those things we read, heard, songs, poems, natural encounters that fill us with life—a mode of scholasticism of natural encounters.

We are tested by writing. Whether that writing is on an essay question or problem that is like a code we must crack, for which we must find the readings that open it up, or scientific findings, which we must back up with literature in the field, same as we do with research based in artistic or humanistic practice, we are being tested for what we have in the scholastic sense read. This a Large Language Model simply will not know.

What if our sources are not texts but images? Then we defer to Derrida, images are kinds of texts in the sense which we read and decode them, or to Bergson, for whom even the brain is an image. Everything that happens with language is of the highest importance.

The change to writing from speaking in the 5th century BCE. The elevation of the word and medieval logic. Then the obvious—the printing press. Now the Large Language Model.

Deleuze's is a strange case because a central theme of his is the critique of representation and—all the way to—its destruction, or, as Dorothea Olkowski writes in a book of the same name, its ruin, Gilles Deleuze and the Ruin of Representation, 1999. For him representation of the sort we see in information and in knowledge is supplanted by the work of the imagination. This is a mistake we make for scholasticism and academic work.

It arises from the work we are doing and as knowledge it follows. But as perception, physical, philosophical, artistic, biological, poetic, it looks out. It is only as we look back that we can see it to have made any contribution to knowledge and to be information.

The mistake the student I was examining made with AI is, whatever the source ChatGPT came up with to the prompt, a misattribution, because whatever their practice is it doesn't have this source. If it were a proper source it would be a point of lookout. (As another of that generation rediscovering the imaginative capacity of scholastic work we might count Raymond Ruyer, for whom it would be a point of survey.)

Where we don't perceive it what is perception and what is association become confused, and what is true of the production of knowledge goes just as well for its collection, organisation and retention. Here is why in the sciences we have the odd situation of bodies of knowledge enclosed in scholastic walls, the cloistering of experts and the siloing of information. We have a situation where research will not admit of its own academicism, of its having to cite sources and do so properly; but among researchers, particularly in cosmology, many recognise the drift from decoding the material data to engaging in speculative theorising, in theoretical physics, supported only by the received wisdom of countless textual sources: that is scholasticism of the old, maligned sort. From this situation we get the critical role of the human sciences in general, to historicise and debunk as convention (to disenchant in a disenchanted world) the received wisdom, their own included. It is as if there were no other role for the human, social sciences—or for theory, as it became known in the '80s—than critique. Here the sequestration from life is simply called the Ivory Tower.

Another academic office door

It was Mary Paul's office on the Albany campus of Massey University. I was shopping around for a venue to get started on my doctoral study, having read it might be possible, hopeful of an allowance to support it. My other schemes to justify my existence had not so much met with failure, nothing so decisive, as been worn out, had dwindled to some loose threads.

I presented my proposed topic, and began citing my sources. Mary Paul said, What I don't understand is why these old philosophers of '68, why now? I was surprised at the question, shocked she might ask it.

I think about how the hopes of '68, of that generation, including the thinkers I've named above, who were involved in it, were disappointed. What did they have to say to us? And in 2025, 12 years later? As Gareth asks, why now?

Armed with the knowledge acquired over 23 years of reading my selected sources I came to the first test of my journey. I might as well have used an LLM to find them. And we strike that word that comes up where works of imagination, like those Gilman-Opalsky accords the value of really existing communism that I have called (source: Guattari) molecular communism—relevance—: what relevance did they have to my practice. I know, I intended the scholastic organ to be sufficient justification that I was doing artistic research, to prove the relevance of my practice in an academic setting, and apologise for its existence.

a biography of the shock

The project I had for Mary Paul was very different from what I ended up doing. It was not practice-led but a thesis on political economy. Mary Paul's ex-husband, in fact, Murray Edmond, has an interesting line on this.

What I wanted to explore was how theatre in New Zealand had been the initial testing-ground, providing evidence of its devastating effect, for the economic policies of the '84 revolution—as Murray calls it, his essay on this topic called "The Man from Treasury." The man from treasury, his speech met with general disbelief, spoke to a crowded room about what was about to be unleashed on the cultural landscape of NZ. It was the same day as Ernie Abbott was exploded at the Trades Union Hall.

A biography of the shock is incomplete without this detail. Mark Jackson took over from Ruth Erwin as my primary supervisor. He told me there was no better place in the world at that moment in 2013 than AUT to do a practice-based PhD. I was eligible for a Post-Graduate Assistantship with a stipend, for which I have him to thank.

The first step towards a practice was forming a group, an experimental theatre group, where my research was to be in theatre. We met in the black-box theatre at AUT, I had asked the School of Hospitality and Tourism to clear the space of the catering equipment being stored there. Black floor-length drapes, lighting bars on electric hoists, good floor, painted black, even a Green Room with monitors which had never been connected, and a lighting/sound booth behind glass overlooking the space: it now houses a virtual production studio.

I had invited some friends, Barnie Duncan, Joe Fish and Jeff Gane. I talked about how we were going to launch an attack on all current theatrical practices on the basis of their complicity with the financialised world-view introduced by the neoliberalism of the 4th Labour Government, 1984. We were to originate our own, this was the experiment, and do so informed by the history preceding it, when NZ was developing a unique theatrical voice, the era that supported my father's efforts, with the end of which our return from West Germany coincided, and his hopes were extinguished. We were to be impelled by the same question impelling him in his decisions as a director of theatre, What is necessary?

What is it necessary to do now? In the Green Room Barnie said, if I'm going to want them to be part of this group, that all theatre is shit is not something young people coming to theatre for the first time are going to want to hear. I was ashamed. Not Barnie's intention at all, and a shock.

I thank him, too. But I had no group, no practice, only the assurance of my supervisor that AUT was in 2013 the best place in the world to do practice-based research. Jeff came back and became central to what we did. Joe and Barnie did not. And most of what happened next happened by chance, which is the overall point I am making.

The object of exegesis is to follow the practical work, without embellishment and ideally without interpretation. The unadorned truth is a practice and its archive is not there so much by necessity as it is by chance. An archive, which is also there by chance, affirms what in a practice is there by chance. The practice is choosing.

There may be no bad choice, of a movement, a gesture, an action or direction, but we can get better at choosing.

This is something we said often in Minus. Even if our sources are random, minor and trivial, to be faithful to them in the scholastic work. This is the engine of its engagement with the world and with our lives.

Why now?

Perhaps out of the impromptu reunion we had there might be more Minus. The occasion was the screening of Chen Chen's—my colleague, a member of the group from the beginning, who gives me work at AUT, where she teaches, like acting as an external examiner, where the shock of seeing an AI credited as an academic source, which has caused this post to be written, has come from, I thank her for her support—documentary film, Little Potato, a poetic portrait of her grandmother in China, the 'little sweet potato' of the title. The film won best short this year at the Doc Edge Awards (see here).

What relevance can Minus Theatre possibly have now? Chen B. who was at the screening —I had seen neither her nor Alex, with her, since 2017 when Minus had its last performance—gave the answer that we have to do something to fight against the Destiny's Church, and children being taught to draw Swastikas. Minus could fight back. It could be a way, she said, but in different words,

The work of the imagination must be defended.