Tomorrow Belongs To Me: art after genocide

The following article is prompted by Auckland Theatre Company's puff line for its 2026 season of Cabaret:

One of the most iconic musicals of all time, Cabaret is bringing its divinely decadent and chillingly relevant dazzling production to Tāmaki Makaurau in 2026. 🎶!

Chillingly relevant?! I asked, commenting on the Facebook post where this appeared, Are you taking a Palestinian genocide angle?!

The reply came, which I am not able to quote directly since my comments and ATC's (Auckland Theatre Company) replies were taken down (for being spam or offensive), that the musical, written 60 years ago by Fred Ebb and Joe Masteroff, has remained popular because of the quality of its writing, that is able to elicit many different individual interpretations.

I answered, Ahm, no. The political context is crystal clear. In fact there's a number in the show about the notion that it's all a matter of individual interpretation which nicely and satirically twists the knife: it ends,

If you could see her through my eyes, she wouldn't look Jewish at all!

Are the Nazis the same as the Jews?

Cabaret the musical came from the stage-play, by John Van Druten, on Broadway in 1951, with the title I Am a Camera, whose IMDb page gives him a writing credit for Cabaret the movie, out of courtesy, perhaps, since he died in 1957. (See also here.) The play's title points back to its source in Christopher Isherwood's novel Goodbye to Berlin, which drew its characters from life, much of it based in factual observation, before any association with the razzle-dazzle of the musical. (Searching the date of its first appearance in print, both Amazon and New Directions give it as 1934, making its author appear even more prescient than he was, in 1939, its actual publication date.)

I think this captures the tone of both the novel and the play quite well:

CLIVE. ...where we bought you those fancy undies.

CHRISTOPHER. That's a Jewish store. That would be Nazi rioting, I imagine.

CLIVE. Say, who are these Nazis, anyway? I keep reading the word in the papers when I look at them, and I never know who they are referring to. Are the Nazis the same as the Jews?

CHRISTOPHER: No—they're—well, they're more or less the opposite. (The champagne bottle is opened.)

SALLY. Oh, that looks wonderful.

CLIVE. And there's a funeral going on today, too.

SALLY. Darling, isn't there always?

CLIVE. No, but this is the real thing. This is a real elegant funeral. It's been going on for over an hour. With banners and streamers, and God knows what all. I wonder who the guy was? He must have been a real swell.

CHRISTOPHER. (Passing glasses.) He was an old liberal leader. They put him in prison once for trying to stop the war. So now everybody loves him.

The fey if not faux naivety, the alacrity in passing over any topic of consequence, what's not to like? and it was liked, winning the 1951–1952 NY Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best American Play. The New York Post called it a ..."striking, intelligent and steadily arresting play ... A both uproarious and poignant dramatization", which also acknowledges that it was a dramatization. In it, the novel's author is the camera, holding steadily on the figure of Sally Bowles, who takes her name from Jane Bowles, her husband writer Paul Bowles. Isherwood writes in the novel:

I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.

Are the themes equally unserious as the surface of these texts would indicate? The second is less 'uproarious' and more chilling.

We are today anyway at a safe distance, the documentary evidence far enough away, but far enough to say that divine decadence or uproariousness and chillingly relevant set one another off, like an olive in a martini? Then there is the reason for it having to be developed, carefully printed and fixed, which has, since Isherwood wrote it and Van Druten dramatized it, become so familiar as almost to render the context in which it was written and performed in 1951, irrelevant.

Whoops! There go Politics! so that we might ask again, as Clive does,

Are the Nazis the same as the Jews?

If we are only doing Cabaret for its theatricality, and its deliberate suppression of political and social reality through overt theatricality, the divine decadence we look back on with nostalgia, are we playing right? Are we doing right by the work? I would suggest we only do the work for the sake of nostalgia, for theatricality and camp, as much as for theatre, if theatre, like literature, have become complicit with suppression.

What would Goodbye to Berlin look like now?

I don't mean, to stay true to Christopher Isherwood's intention, but to his artistic conception; and, following from this, the play, and film which came from it, having been relegated to its pre-history, that of Cabaret: what would Cabaret look like now?

The question is both ingenuous and leading. I am assuming we know. It would look iconic, chillingly relevant and divinely decadent, as in the dazzling production to come to Tāmaki Makaurau in 2026.

Sally Bowles is an on-screen icon in Liza Minnelli's performance, and we can take it from the short excerpt above that she was for the novel, an icon, even in her tawdry domestic setting, to be fixed forever in a photograph. Isherwood however has upset in mind, Sally and the theatrical world she inhabits, Berlin's Kit Kat Club, are about to become not icons but relics. They are overtaken by a contemporary moment on which they have no purchase, artistically—or purpose—in which they are supererogatory. As much to celebrate their theatricality as their vanity, and to mourn it, this is the purpose, the artistic purpose, behind Isherwood's photograph.

Where would we look for an analogue today? Modern commentators on our political situation might suggest America, but could we ask with Clive, Are the Nazis the same as the Jews? and answer with Christopher they're more or less the opposite?

Could we go to the heart of the contemporary genocide (without a doubt there have been others; that there will be, on the evidence of this, also goes without a doubt) and be asking the question Clive does? Is Hamas the same as the Knesset? And are the Jews the same as the _____? If we could, what is doubtful is we could answer as Christopher does, that they're more or less the opposite.

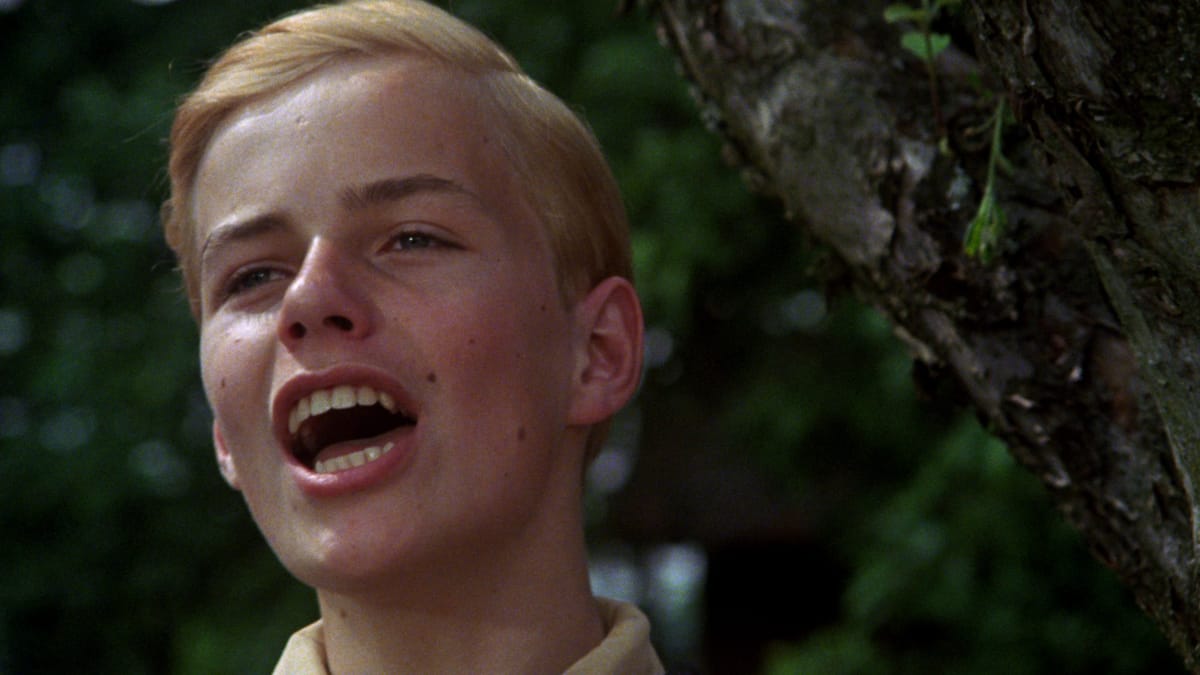

Or, since we are considering a musical production produced for a New Zealand audience, is there a parallel there? There probably is a closer one than at any time since the Muldoon era. David Seymour, head of the Act Party, currently Deputy Prime Minister, jumping up and singing "Tomorrow Belongs to Me" would make good satire. Since we are online, we can remind ourselves how it goes:

Satire is however neither Isherwood's, Van Druten's nor, the director of the film, Bob Fosse's artistic conception, but can we say that without the political context of the late Weimar Republic and the start of Nazism Cabaret works? If Cabaret is an iconic musical, it owes a lot to the contrast between the historical and political reality and the theatrical one, which brings us necessarily to a consideration of our own historical reality. And this is where artistic responsibility comes in, where and when it is irresponsible not to ask whether the opposition so boldly put in the play between Jews and Nazis still holds.

That it's complicated is as it should be. Smoke rises from the fire ignited by the association and alleged complicity between left-wing icon (yes, that word) Noam Chomsky and Jeffrey Epstein: are icons the same as perpetrators? Whoever the smoke is fanned as a smokescreen for, is the left opposite, except anatomically, the right?

If they are found after all to be on the same side, is pro-Palestine the same as anti-Semitic? And where, anti-political sentiment being rallied by conservatives, not to say fascists, does Antifa stand? It might be too complicated for a musical but to say it doesn't belong, as politics does not belong in sport, the watch-cry of the anti-anti-apartheid movement in New Zealand during the '81 Springbok tour, is incorrect.

In any case, I am not talking about taking political responsibility but artistic responsibility for what is true and good about the artistic conception behind one of the most iconic musicals of all time. I am not arguing that without taking its political context into consideration a production of Cabaret will be politically irrelevant, but that without it it will be artistically irrelevant and that this is theatrically irresponsible. I am also asking how can you not take its political context, which is its historical content, into consideration in our new age of genocide?