Stranger than Fiction: taking 20th C. novel to the gleaners

Edwin Frank writes:

"Trembling instability" describes the mobile perspective of Lawrence's novels (if they were films, the camera would be handheld). Lawrence writes, as I have said, with an almost somatic immediacy from the point of view of his characters. He also and equally writes from his own point of view. As his books unfold, you feel his character and interests. This could be described as free indirect discourse, but in practice it's quite different. Free indirect discourse typically constructs a neutral narrative space that allows writers to pivot conveniently from the view from within to the view from without, permitting them to present characters' motivations and actions in what appear to be their own terms.

...

Neutral space? There's not an inch of it anywhere in Lawrence's work—the space of his books is charged through and through—just as there is nothing like old-fashioned omniscience. Far from knowing what's going on, Lawrence the writer, like his characters, is perpetually in the thick of figuring it out. In a broadside from 1923, "Surgery for the Novel—or a Bomb," he wrote, "It seems to me the greatest pity in the world, when philosophy and fiction got split. They used to be one, right from the days of myth . . . The two should come together again—in the novel." This remark conveys Lawrence's open-ended commitment to feeling as thinking and vice versa. Even more characteristic is how this explosive essay ends with an image of the modern novelists tentatively slipping like sheep from one field to another through a gap in a wall to discover a new world.

...

Trembling instability is also apparent in Lawrence's very sentences.

– Edwin Frank, Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel, Fern Press, 2024, p. 276

Frank goes on to talk about Lawrence's use of repetition as resembling an hesitation, a stuttering of language, which is a theme of Deleuze.

Deleuze's use of indirect discourse is also recalled here and Loren Eiseley's evolutionary niche-finding as being like finding a gap in a wall (in The Unexpected Universe) is also brought to mind.

For Eiseley, our species is less a product of natural selection based on struggle than on escaping from it. Eiseley implies that the gap through which humanity slips is into language and that from language, by language, failure is averted; he reminds us however that from the viewpoint of natural competition the species is a failed one. Now this notion of language as interior which exteriorised becomes instrumental also connects to the embodied thought as that which the products of technology are, an allotropism of the attributes of thought and matter. (see Technology series (I – IV) for this view of technology)

Lawrence in a letter (at Frank, ibid. p. 277):

Morality in the novel is the trembling instability of the balance. When the novelist puts his thumb on the scales, to pull down the balance to his own predilection, that is immorality. The modern novel tends to become more and more immoral, as the novelist tends to press his thumb heavier and heavier in the pan: either on the side of love, pure love, or on the side of licentious "freedom."

—when what is at stake for Frank in Lawrence's work is—innocence.

Again, recalling Deleuze's singularity, of Riderhood in "Immanence, A Life," Lawrence on The Rainbow at Frank op.cit. p. 270:

You mustn't look in my novel for the old stable ego—of the character. There is another ego, according to whose action the individual is unrecognisable, and passes through, as it were, allotropic states which it needs a deeper sense than any we've been used to exercise, to discover are states of the same radically-unchanged element. . . .

That which is physic—non-human, in humanity, is more interesting to me than the old-fashioned human element— which causes one to conceive a character in a certain moral scheme and make him consistent. The certain moral scheme is what I object to. In Turgenev, and in Tolstoi, and in Dostoievsky, the moral scheme into which all the characters fit . . . is, whatever the extraordinariness of the characters themselves, dull, old, dead.

The physic non-human in humanity points to the value of what I hold in "3 essays 3 endings," warranting a re-naming of the historic humanities, to be inhumanities.

It also points forward to what I have been formulating to myself as natural perception, the perception of the cells, in their coordination in a life, themselves, whether of those cells making up the organ of the eye, as of the whole organism, that is, comprising, part and whole, the virtual multiplicity of an organism.

To natural perception I believe we can attribute the appearance both of the double, in art and literature, and of the monster, at the end of the 19th century. The double has a different role however since it doubles a lived duration and so is cinematic in nature. (see Bergson, Deleuze & Cinema, forthcoming, and to receive serialised, please subscribe:)

Frank, where he is quite revelatory, on Musil's The Man Without Qualities:

Arnheim is, in a sense, what Ulrich might have been if he had not known better—or might have been had he not had the courage to know less than the everything that Arnheim feels continually compelled to make an appearance of knowing.

— Ibid., p. 232

Frank on what Forster wrote of Woolf, "It is always helpful, when reading her, to look out for the passages that describe eating. They are invariably good . . . She had an enlightened greediness." Frank adds, "Hemingway's novels can seem to be nothing so much as a count of bottles of good wine and omelettes aux fines herbes." (p. 223)

[Ettore] Schmitz/[Italo] Svevo gave up any dreams of being a writer, devoting himself to working in his father-in-law's business, for which he traveled frequently, sometimes as far as London. Wanting to improve his English, he hired James Joyce, "At that time . . . a fashionable teacher of Trieste's rich bourgeoisie," as a tutor. The two men hit it off. Joyce read his stories to Svevo. Svevo have Joyce his novels. Joyce admired them.

— Ibid., p. 242

That Leopold Bloom is Jewish is explained by his friendship and admiration for Svevo, a "Triestine Jew," writes Frank, "from the business class who was educated in Germany."

Having asserted the war, the Great War's centrality to Proust's vision, Frank continues that that vision is born of two warring elements:

On the one hand, he has an unforgivingly deterministic vision of human nature in relation to the passage of time, by which our bad desires and bad habits—and since in Proust desire is always desire for the wrong thing and habit nothing but a misguided persistence—drag each and all of us to perdition and destruction. ... Then again, on the other hand, by contrast to this predestined doom, there is the saving contingency of the madeleine, of the cobblestone, of the piece of music or work of art that absorbs our attention and sets free our desire (or sets us free from it), moments of redeeming grace—everything that sets the narrator, the writer, apart from Charlus and everyone else. There is nothing we can do to make this happen, though when it happens, there is no denying it. Proust's novel is full of chance events, underwritten by the impossible conceit that the whole of it is one immense transport, a transcendental glimpse.

— Ibid., p.176

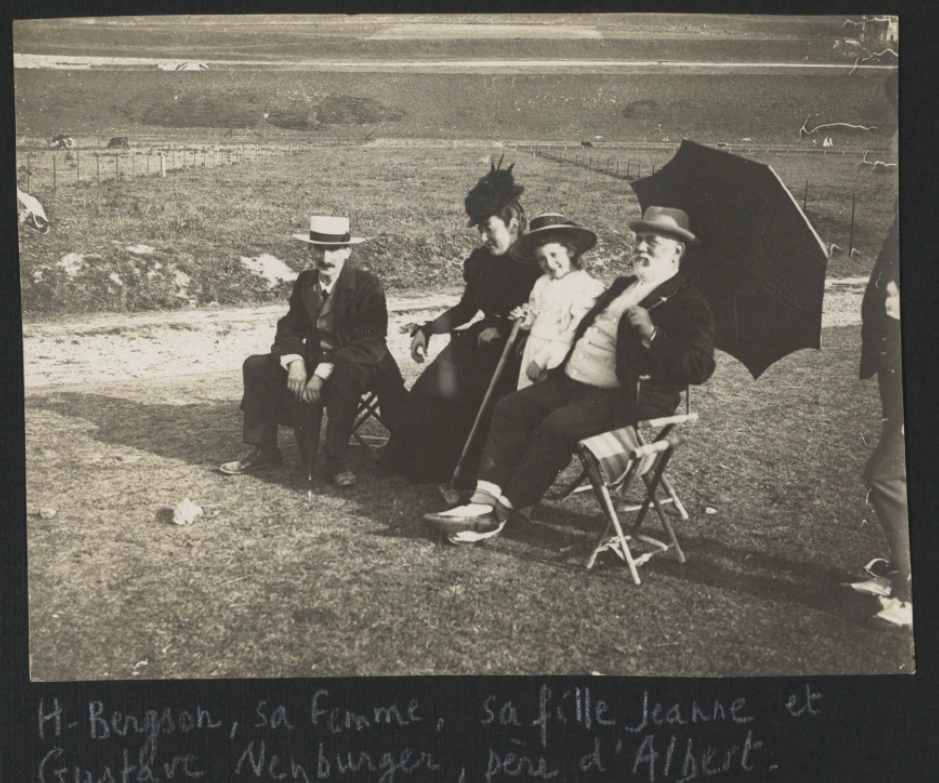

The repetitions of 'vision' on the one hand, the state of historical unspooling being deterministic in nature, and on the other, contingency, the contingency of "the leaves on the trees are moving," both point to a sensibility altered by the advent of cinema; and that Proust was Bergson's Best Man when the latter married the former's cousin, Louise Neuburger.

Proust fell in love ... a young man ... previously employed as a chauffeur, Alfred Agostinelli ... developed an ambition to train as a pilot ... Proust ... paid ...

— Ibid., pp.164–165

Agostinelli escapes with girlfriend ...

Learning that he was in the South of France and continuing to train as a pilot (under the name Marcel Swann), ...

In April 1914, in the course of taking his second solo flight, Agostinelli crashed into the sea ... Proust, heartbroken, was consumed by guilt. ...

Agostinelli was interred and commemorated and exorcised in Proust's pages as a new character—Albertine, met at the beach in volume two but coming eventually to occupy two whole volumes of her own, her name tolling through the pages of In Search of Lost Time. It is repeated, his biographer Jean-Yves Tadié says, 2,360 times.

— Ibid., pp.165–166

The Prisoner is the hellish center of Proust's research ...

... the narrator becomes more and more persuaded that Albertine, who wants to go out, is going to cheat on him with other women. (She is.) Meanwhile he goes on not writing his book, the book that has led him to cut himself off from society. (Meanwhile, Albertine keeps asking him if he's making progress on the book.) The main action of The Prisoner takes place over three successive days—the numbering of them establishes that the days, each filling countless pages, are both interminable, all one and the same, really, and numbered—during which the narrator's jealousy swells to the hypertrophic dimensions of an immense, sickly-sweet tropical flower.

— Ibid., pp.167–166

... Jane Austen. In the very title of Sense and Sensibility, the perils and possibilities of two distinct ways of perceiving and responding to the world are presented for our consideration (and amusement): one (sense) alert to the world at large and to the consequences of our actions; the other (sensibility), which attends to the world of feelings. There are, in other words, claims that the world, or society, makes on us and claims made by the self, and within the capacious and welcoming confines of the great nineteenth-century novels that follow from Austen, claims of both sorts must find accommodation. Indeed—it is implicitly suggested—it is simple common sense to recognize that only by integrating these two views can a proper—realistic—relation to reality as a whole will [sic.] emerge, whereas clinging exclusively to one or the other way of seeing things will lead to disappointing, if not tragic, results. Yet the seemingly simple imperative of responding to the summons of common sense turns out to be much harder than anyone would imagine, or so the nineteenth-century novel works to show. The problem is of infinite interest, in fact—and significant risk. ...

Description or imitation is of course central to the power of the nineteenth-century novel, but its vaunted realism doesn't stem from its many realistic effects, persuasive and pleasurable though they are, so much as it does from the judgment it displays in assembling such features of the common human predicament for our consideration. Character and situation, expressed and explored through a reliable interplay of dialogue and description conducted under narrative oversight: that's the form the novel settled into in the nineteenth century, and which the vast majority of novels take to this day.

— Ibid., pp.20–21

The plot of a nineteenth-century novel is in a way analogous to the developing representative politics of the nineteenth century ...

The novelist must find a place in his pages for all his characters, with all their various motives, and keep things under control (even as they threaten to break apart). And all the time, the novelist is also working to obtain the reader's vote of confidence.

None of these things are on offer in Notes from Underground ...

— Ibid., pp.21–22

... which is why it is the first novel Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel considers.

[to pg. 295] [biggest revelations: Musil {Man without Qualities}; Wells {early work}; Hemingway {first work}; Dostoevsky {Notes from Underground}]