moving image: theory | context: lecture 1

Welcome to Theory and Context.

This first lecture we will be discussing theory. And context. ...

Like the label says: we will be discussing theory and context, in respect of their relevance, or irrelevance, to the different formal expressions of film, animation and game.

The concept here, theory deals with concepts, is ‘formal expression.’

Why not stick with ‘form’? Or do away with the concept entirely: in their relevance, or irrelevance, to film, animation and game?

In that case, it would be quite simple: theory and context of film ... theory and context of animation... same of game...

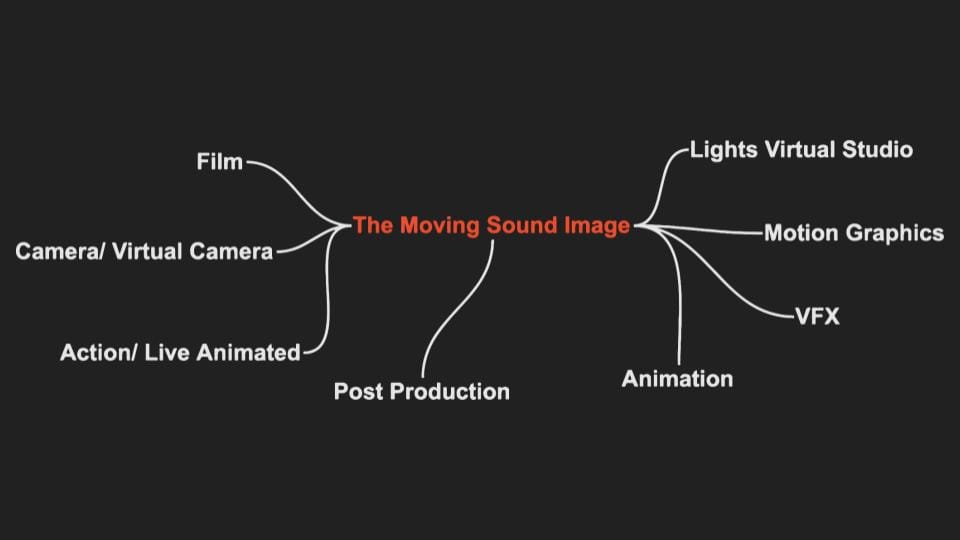

But what we would be missing is what these forms have in common. This is the moving image. To be more precise the moving sound image. ...

We’ll get around to discussing that.

So, film, animation, motion graphics, VFX, post-production techniques, cameras, lights, action, interactive gaming, digital and video art, all deal with the same thing.

We can start to apply some rules which define the moving image or the moving sound image. Except...

and this is the reason for that other word I added, expression.

What we are dealing with is making moving images (take it as read that that includes sound images). Making moving images we are making use of them.

To do what? To express something. Different things.

Different so that they become different forms of expression that have their basic means in common, the moving sound image. (It just sounded better saying sound that time.)

We’ve strategically left out the question of relevance, or irrelevance. Who wants to prove the relevance of either theory, context or formal expression!?

And, if we are dealing with making use of moving images as means of expression, why don’t we just get on with making them?!

This is the reason for adding ‘expression,’ not because moving images are means of expression, because defining the moving image by its form leaves out something very important.

We’ll come back to that slide at the end and we’ll leave that question hanging for now, but I’ll give you a hint, it leaves out what the anti-vaxers love to shout.

(No. Not that one.)

Why have a course called theory and context running alongside the practice, the practices of making visual effects on film, animations and games, and the studios where we do those things and learn how to use the practical tools?

The question of relevance is of the relevance of theory, and context, to practice.

What this course has to do must be something like provide us with the theory, the ideas around what we do in making, for film, animation and game, and the context, possibly the history of these different forms of expression.

... but as forms of expression... but it’s already quite strange, because we don’t yet know what we are going to be expressing...

Will theory, ideas about film, animation, game, and the history of these forms help? Perhaps.

Or is it better that the course provide us with the rules, the formal principles, according to which the different forms of our expression make use of the same means, images, moving images, with sound, sometimes?

You can perhaps see the problem:

The choice seems to be, either to give what are we are going to create, that we don't yet know, a place in theoretical discourse; or, to give it, in the worst case, rules it has to follow, in the best case, guidelines. For what? Best practice, I suppose, but let's deal with these two options.

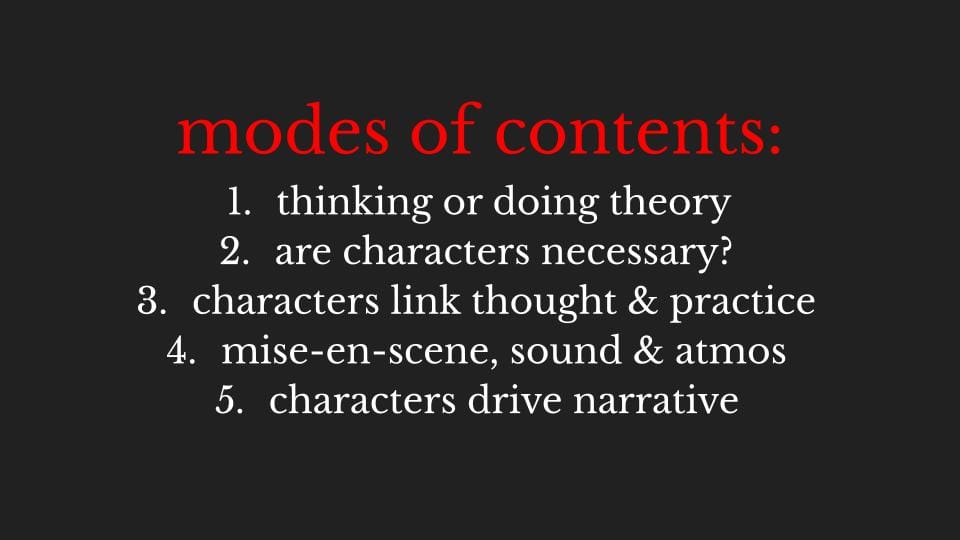

First, theoretical discourse. This course is called theory, so there must be some theories floating around on the subject of moving images in general, and game-making, animation, the digital, and film more specifically.

Discourse means simply what is being talked about: so it is in the air and therefore a product of its times.

In other words, discourse is what has already been said about these subjects. What has already been said, as well as what is being said now. We hope.

We hope that theoretical discourse applies to the present time, otherwise, that old stuff, what's already been said, might not be relevant, to us, now.

And there's another side to this: in noting that what is said as theoretical discourse

is the product of its times we are at once noting its historicity.

So this would be another theoretical concept: ‘historicity.’

The fact that what is said as discourse comes from a particular historical context. (There's that other word, context.) A particular historical context by which it is either imprisoned, in a way of thinking that was perfect for the times but is way out of date now; or, a particular context in time that still applies.

This concept doesn't only apply to theoretical discourse.

It applies to all discourse, including the one we are in the middle of now.

And we can't avoid making the value judgement: the closer to the present, the more relevant to us, yes?

No. We must read the present as having its own historicity. Its own prisons for thinking. Its own limitations and an equal potential for irrelevance to that discourse that includes theoretical discourse belonging to past history.

Why?

And this is the first lesson of this course: if we don't read the present as having its own limited perspective we will repeat it.

We reverse the famous saying, those who don't learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.

Still, that can't be too bad. To repeat the present.

But what does it mean?

It means to limit ourselves to what has already been said.

In practice, it means limiting ourselves to what has already been done.

It means conceding the idea there is nothing new under the sun. And that we cannot make anything new. It also means accepting the present under its own terms.

It becomes like an app that we are forced to use, that has limited functionality, in the best scenario. Or that doesn't work for us, in the worst.

So the present can be disappointing. This we can accept.

Or it doesn't work for us at all, and we accept we can do nothing about it: we can change nothing. It is what it is.

Of course, that's another value judgement. A conscience call: why would we accept the terms of use of the present?

To gain the limited functionality that it has.

The question is, why not reject that limitation?

The second lesson of historicity is that we can see our own discourse, our own thinking, that is theoretical discourse because it reflects on what we do and how we do it; we see our own present situation, in front of a screen listening to quite a confusing lecture, as a part of series of circumstances. This allows the series of circumstances to be reflected on independently, independently of our, for example, use of the app.

The present belongs to a chain of circumstances that brought us here. It has its own historicity.

So the big take-home point lesson of theoretical discourse is that it allows us to reflect in the present, on the present. It gives us a little distance. Makes a tiny gap, a bit of time. Do we do this? Or do we do that?

The French philosopher, Henri Bergson...

writes that the advantage of a nervous system as elaborate as our own, the advantage of having a brain, is to produce this tiny gap between perception, the Ow, that hurt! or the Hmm, nice colour, and action.

If you think about it, the signal takes longer than in, say, a dog: aggression?

Now I'm in attack mode!

From that, to:

their historical situation has given these online trolls the opportunity to act like they hate, but they don't know me.

And if I attack right back, I give more hate-juice to their mean and petty lives. ...

Or... maybe I shouldn't think about it like that at all.

You see, I have this hesitation over what action to take, in which a thousand options present themselves... well, at least two or three. And, Bergson says that they come in the gap:

first option: attack!

Part of my brain says, You know you want to! and prepares itself, that is me, for attack.

Pulse up, check. Body stress alarms going. Check.

Then, what comes to mind is another perspective:

second option: is the suggestion of a niggling feeling: a niggling feeling that doesn't allow me just to attack.

It doesn't yet offer an alternative. It makes itself felt, and I have to dig into it if I want to find out the details.

Still it is enough to prolong the pause.

This pause, this hesitation or gap, is not between thought and action: the thousand options present themselves at the same time. Or at least the two or three do.

And although my body is switched on to attack, part of the stress it feels is coming

from the conflict between these different impulses.

That is, they are impulses felt in the body as much as images, ideas or thoughts.

third option, which is really a continuation of the second, since it asks me to look more closely at what is stopping me from acting immediately and it too is immediate:

I recall all at once other situations that fit the current one. And it, the current one of being trolled, pours in like a mold...

Despite the differences, I'm filled with a sense, even before really thinking about it, definitely before I call a friend for advice, I'm filled with the sense that this situation recalls. And I can see I am conflicted.

I am not just in fight or flight mode. And if right then I attack I know I'm prepared for it.

And if right then I pull back and think of some witty quip, some clever comeback, to ward off the danger I'm prepared for that too.

I'm also and equally and immediately prepared to attend to the memory that presents itself. And to really see it in detail, get its time-stamp and see if it calls for a different course action because the fit I'd felt between the sense mold and the feeling that filled it just now might not be exact.

What are, as they say, the extenuating circumstances?

But I attack anyway.

What's interesting here is that for Bergson the brain and nervous system are plugged directly into the image of my situation of being trolled, right now, in the present.

And this is Bergson's weird use of the word 'image' because it means an actual lived situation.

What's interesting is the detour I'm led on out through the hesitation into an interior sense of time that has a distinct duration and enables me, eventually, once it has prepared me for all sorts of eventualities, to consider my options.

What's most interesting and goes against what we normally think the brain is doing when we think is that it's all about impulse, movement, action:

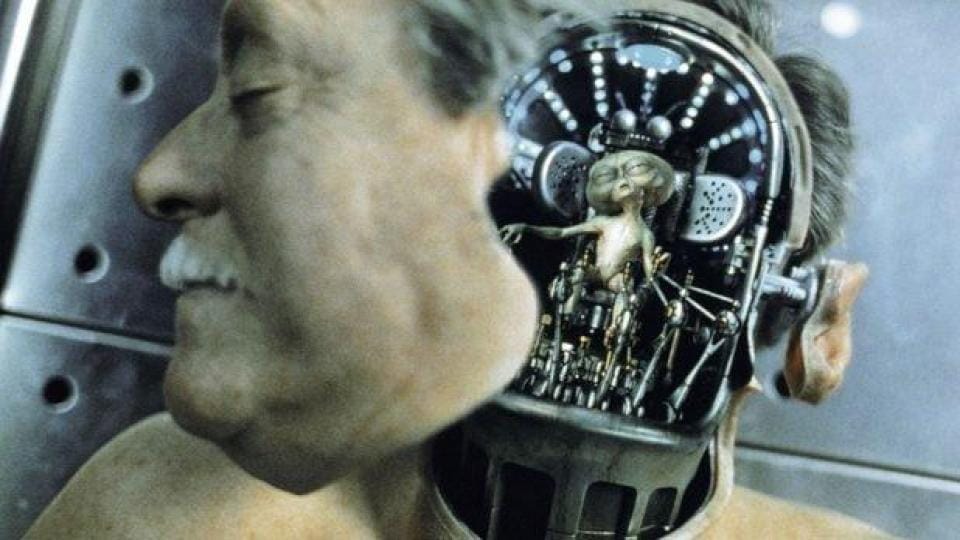

perception is not drawing a picture inside our heads, or wherever, of what's going on. Perception is not inside our heads.

There's not some little guy in there sitting in front of a big screen with a direct feed onto the outside world who rubs his little hands together, who is like the Wizard of Oz, and says, Now, which button do I press? What lever? What do I do up here in the brain

what do I do that's going to make this ol' body take the relevant action and type those words it so wants to type, those names it so wants to yell, that will destroy any sense of self worth the person receiving them has and tells them and their mean and petty life they can rot in hell?

Nothing like that:

the body is part of the image:

that is, it's part of the scenario and is being prepared to act by the human brain and nervous system which is less like a screening room and more like a relay station:

it controls the circuits, and their lengths, the lengths of their duration, taken between the perception... which is only ever a sampling of the whole reality, because it subtracts from the whole reality this little troll, and frames the image so that everything else is out of frame, and in the frame is exactly what bothers me, between the perception and...

revenge!

The brain is an image among images. Then, what is the role of moving images?

What is the role of the moving image according to this theory, and in the context of the troll scenario?

Bergson says that perception is not made up of representations of things. Perception is already outside. Outside the brain’s screening room. Outside the screen, which is only ever a framing of it, a sampling of it, that subtracts from all the images what is interesting to me, now.

What the moving image, the moving images are doing, is exactly what the brain does.

The brain and the elaborate nervous system of the human being. The moving image is the further elaboration of the nervous system and brain.

The moving image extends perception. It doesn’t express it and it doesn’t represent it.

And this Bergson saw in his time, in the context of images showing natural processes slowed down, in slow motion.

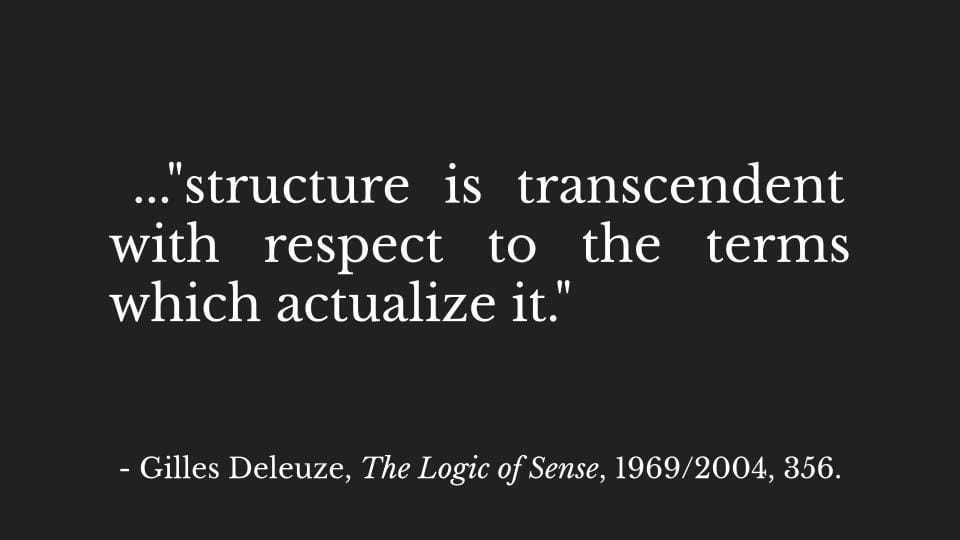

It remained for another philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, to draw out the implications for film of what Bergson had written. But it’s enough for us now to make this suggestion:

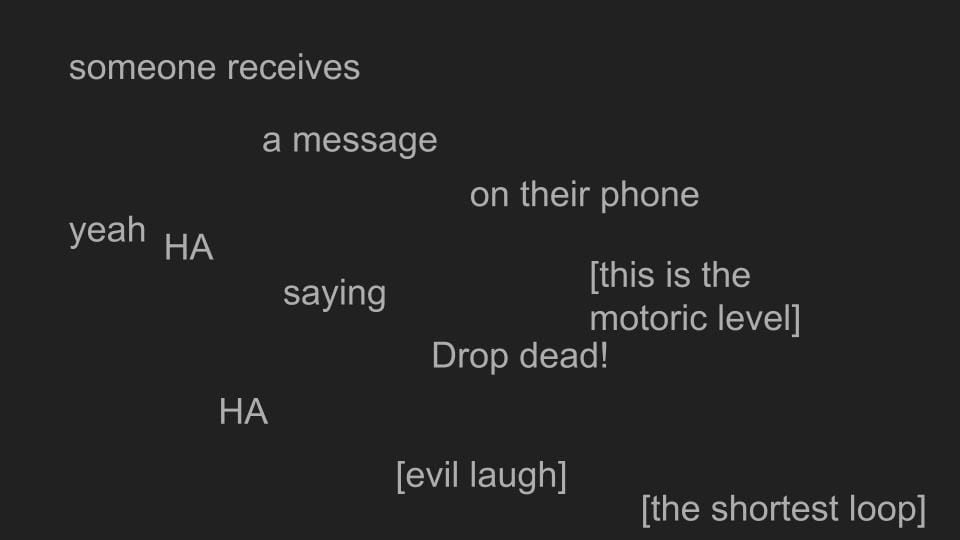

1) someone receives a message on their phone saying to drop dead. This someone doesn't react immediately. But we can see they want to.

This is the motoric level, the shortest loop...

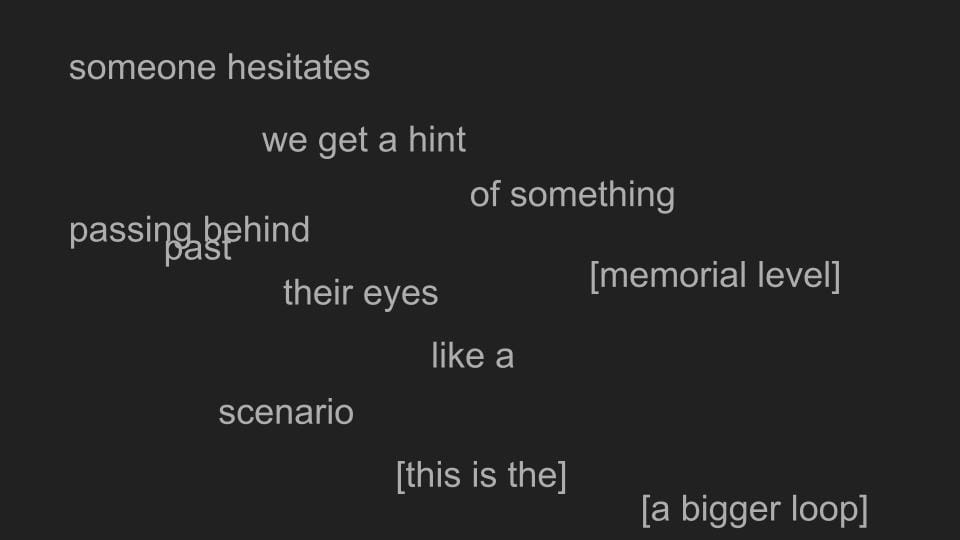

2) This someone hesitates...

And we get the hint of something passing behind their eyes... Like a past scenario.

This is the memorial level, a bigger loop, a longer hesitation.

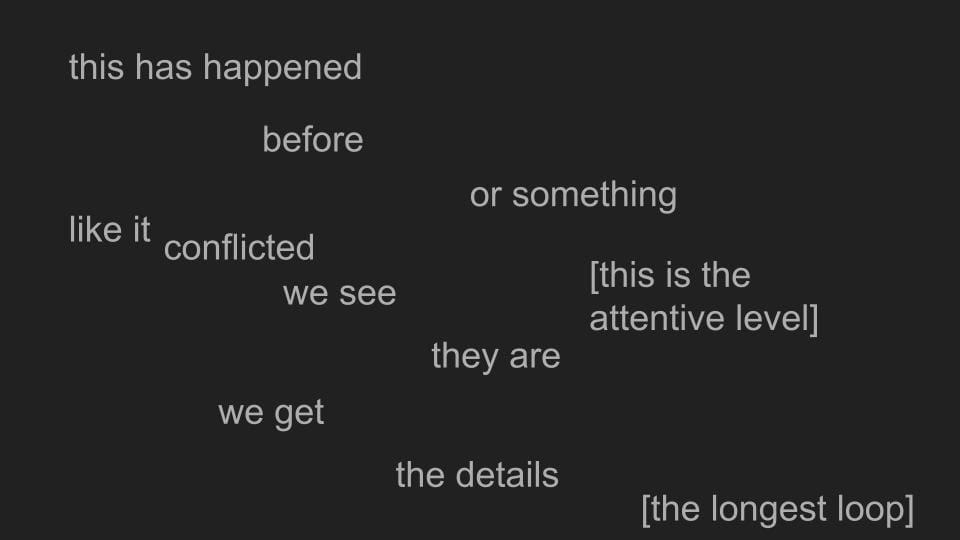

3) And helpfully on the screen we see that this has happened before, or something really close to it. We see the someone conflicted. And we get the details of why.

This is the longest loop. It takes us on a detour through the last 24 hours of our character's life, or even the last 24 years.

It’s Not a flashback, all three levels belong to memory.

This is the attentive level.

And why would we follow what has been done before so closely? To be liked, of course: so that what we make, what we create will be liked also. And so that we won't have to say, Oh, I'm sorry, I went a bit crazy there!

We want to stick inside our own timeline. Because it’s the only one that’s relevant to us.

And yet... and yet...

We can’t help thinking...

because through this gap Bergson draws our attention to, inside this hesitation, which can last no more than a nanosecond, or the two to three hours we sit in front of a film, or the fortnight we spent playing Fortnite, one lifetime or several, through it come all the characters we see, as we will see in the next lecture, and we are plugged in to all the images to find and frame what interests us, the possibilities of which we are the free expression.

Back to expression: the reason I added it to form, invoking the concept form of expression is this:

it makes no sense to speculate on what a form of expression is going to be. Until it is expressed we don’t yet know what use of the image it’s going to make.

Neither do we know what its structure is going to be...

because a theory of the image, of the moving sound image, follows the image.

And so do the guidelines, in the best application of a formal theory to film, animation and game, and so do the rules, in the worst application of a theory of forms, or good form, composition, balance, pace, and so on: they contain moral judgements which limit their expressive potential and imprison possibility to the already seen and done. When the use of memory, as Bergson puts it, is always creative.

A theory applied to a field of expression is always exegetical and never speculative or thetic. It does not advance a thesis. It follows the image.

The structure it finds transcends the terms of the image in which it is actualised. That is, expressed.

This brings us to our final point. How do we think not about practice, but in practice?

The answer might sound like a trick: the practice thinks, and that’s what establishes its form.

The clip from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. The shot sequence expresses a thought. Not a thought of, allowing us to ask, What is the thought it expresses? And go in for all sorts of speculation, advancing all sorts of ideas and interpretations as to what that might be.

It is one of the most famous and famously creative cuts in all of cinema. The bone sails up into the air, the spaceship floats down through space.

That’s the whole thought. (And notice how it has the formal expression of a thought, operating through one of the simplest cinematic devices, the cut.)

Background, for those who don’t know the film: the ape who throws the bone has discovered its use:

he (we presume he) uses it to kill a tapir which his group, his tribe, is nourished by:

and it is then as a weapon against another group of primates, early humans, that the bone expresses its use:

the ape uses it to beat another ape, who is the leader of another group of apes, to death.

The bone is a tool, a weapon, a technology.

It extends and amplifies the force and strength of the hand and arm. It supercedes the old technology apes come equipped with, of teeth and claw and the strength to tear limb from limb.

It elaborates a potential, a new potential.

It thinks it, if you will; and before the clip we see the ape’s hesitation and him slowly coming to terms with what it can do. Learning what it can do and through it what he can do. What it can do that he formerly had to use his teeth for, or claws, or to organise the whole group to achieve. (Yes, a social organisation is also a form of technology.)

And the spaceship: exactly a technology. A technology is an elaboration upon the nervous system and brain. (And note here that this goes for nonhumans as well, from the elaborate habitations of termite mounds, with their central heating and cooling mechanisms, to the quantum technology involved in the internal compasses of migrating birds, and butterflies.)

This film 2001 is about film: it is a huge hesitation that thinks about the elaboration of the possibilities of what film technology can achieve.

Alien contact with humans is first made when the pre-human ape finds a new possible use for the bone, a technological one.

Alien contact in the second instance occurs when, in the year 2001, a group of scientists (another group) take out and use a camera on the moon.

The clip...

Oh, before that: what do anti-vaxers shout? Freedom.

And an explanation for the form of this lecture: I wrote it. But in writing it, I didn’t know what I was going to say, only that, when the first day of lectures arrived, I would read it. In other words, my thinking had to pass through the detour of this technology, the technology of writing, before I could think it. And what is masquerading as my thinking is as much due to the gap between thought and written expression, expression that is, in words, just as much in images, as film is.

Of course, they are different forms of expression.