moving image: theory | context: lecture 2

Last week we covered how moving images think.

A moving image sequence is either a simple or a complex thought.

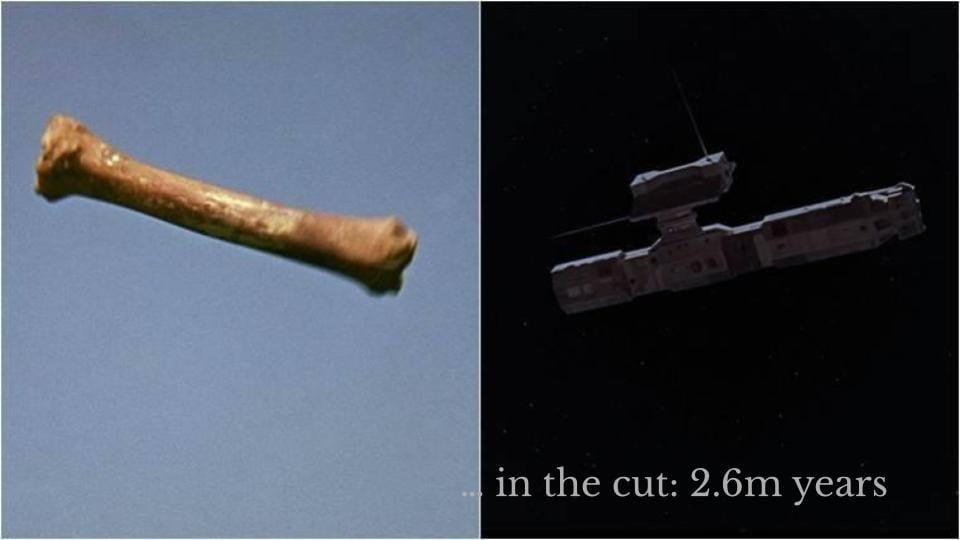

A bone turns into a spaceship is either a simple or a complex thought, because this is what the cut does, it is a movement cut that leads us to associate the bone flying into the sky with the ship descending through space.

As a complex thought it tells us about 2.6 million years of history.

Of the evolution of the human which is also the evolution of technology:

This cut is often said to show 4 million years. But it is more accurately 2.6 million years, because 2.6 million years is reckoned to be the length of time between the first tool use and now, where, in a sort of historical irony, we are way past the year 2001.

And where are the spaceships?

In the cut: a movement cut, from one thing moving in the frame, which we then relate to the next in movement and of a similar form:

the entire development of human technology. From its weapons to its social organisation, and to its outsourcing of the capacities of the organism’s innate or inborn capacities, those of its brain and nervous system as much as those of its body, to technical means:

the bone extends the arm and has the weapons value of the big teeth and tearing claws and strength to use them of our primate ancestors:

film is an extension, the moving image sequence, of the hesitation, the gap in ordinary time, that is, the time measuring action, calculated at its maximum to be the speed of light, a gap through which we can consider other possibilities for action and for life.

Computers don’t do this. Despite the excellent press this technology gets, microprocessing and now quantum-processing are just that, processing, calculation.

But coding, coding is such a technology, as any writing, allowing us to dream of new possibilities.

AI to be AI will have to learn to write code.

Notice how Rafik Anadol uses ‘memory’ to talk about the algorithm’s image processing. And then ‘hallucination.’

Also it’s interesting that a ‘machine’ should remember a human world without any humans in it. Despite the variation amongst the millions of images, the visualisation resembles a single image. A single image in continuous metamorphosis. And less a moving image sequence.

The timeline for this cascade is linear. There is no internal loop breaking the flow, no gap or cut, or any hesitation at all, that would indicate inner experience, such as memory.

Last week we also touched on the importance of theory, to help us create, to notice things, about our work, and to take a step back:

that hesitation again, and begin to think, in ... images.

Another way of talking about this hesitation is to talk about going by way of the outside. It’s always to use a technical means, whether writing, film techniques or social organisation. ...

So thinking is never ‘going into your own heads.’

Theory does not mean getting stuck in one’s head.

Again, the simplest film technique, the cut. Between a bone and a spaceship. In the cut we travel 2.6 million years.

Kubrick as much as anything shows us this possibility for thought.

If only we could cut spacetime as easily as thought does. We’d have spaceships. But we do!

We know the Millennium Falcon better than the Apollo missions.

This course, since theory is a written medium, uses the technology of writing. But that’s something to consider:

that you are not being asked to rely just on your own innate or inborn capacities, to think with your heads or brains:

you are being asked to think using writing and using reading.

So this is what I should have asked you to do from the start:

when you’re reading, make notes. Get used to thinking in writing.

Yes, reading is a technology too. You think you know how to read, but knowing how to and knowing how to use reading are two different things.

You remember Bergson’s levels of memory?

Knowing how to read is motoric. It’s a habit. A good reader doesn’t even notice the words. She surfs the sense.

The next level is memorial. It’s coming back to something you recognise, that’s familiar. It’s comforting.

It’s I get it! It’s recognising, for example, one’s own mother in the character of the mother, one’s own experiences as those of a character or fulfilling one’s own wishes in what they get to do.

Then there’s attentive reading, which combines these.

Yes it goes back to memory, but to try and make sense of the words.

Yes, it goes back to habit but as if it’s trying to break the habit, so that you notice the words. And they’re unfamiliar or they’re used in a way that’s unfamiliar, and you want to throw the book or the laptop or the tablet at the wall.

What to do, reading Bergson, or any of the readings, when that happens?

Think it through in writing. Using your own writing. The words you know. The words you don’t.

In other words, outsource the thinking to the screen or page. Not to Google, but to the empty page.

Write out what you think the sense is.

It’s like learning to surf by getting some lessons.

Above all, get your balance, try surfing the smaller waves, the bits of the texts that you like, before going out to the main break. It’s like following the movements of what you’re reading with your body and finding out what works for you.

And then putting it to work.

The technical tool that tells you where you caught hold of something that really got you thinking in writing is referencing.

Note name of author, year of publication, title, and page number for books; and...

name of director, year it came out, title and production company for moving image and film, where instead of page number, note down start time for the image sequence that grabbed you.

While we’re here I should introduce the first assignment, which eases us in to using just the technologies of writing and reading, because it also uses drawing:

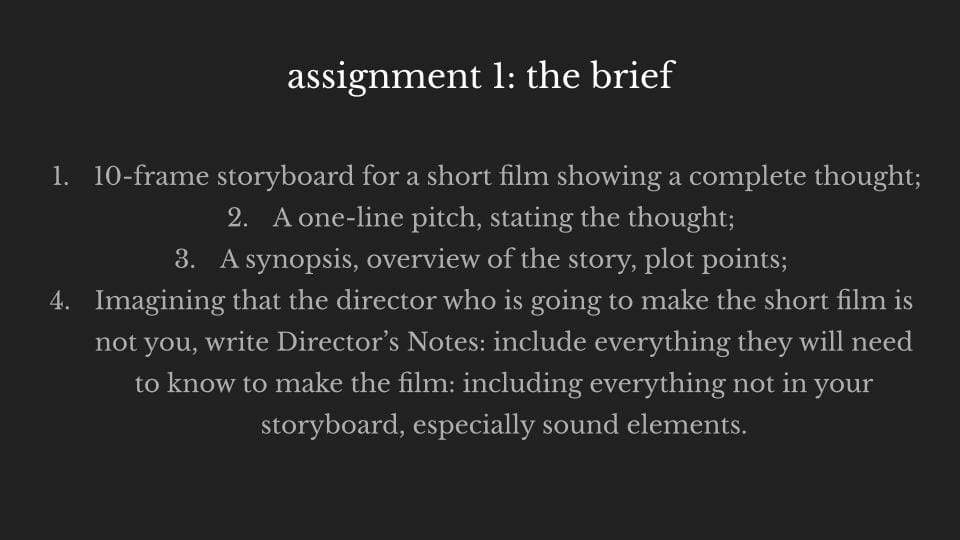

The brief is to make or draw a storyboard of ten frames for a short film that shows a complete thought.

Give it a one line pitch, a pitch stating the thought.

Plus a synopsis (which is an overview of the story) and, imagining that the director who is going to make the short is not you, write director’s notes, including everything they will need to know to make the film how you imagine it to be.

This includes sound elements diegetic (ask your tutor) and, if you want, music. Everything that is not already obvious from your brilliant drawings and storyboard. It should have these elements:

10 frames of storyboard for a short film

A title

A one-line pitch: what’s the idea?

A short synopsis

Director’s Notes—written so that someone who is not you can make the short film, including sound elements, both soundtrack and diegetic (if you intend it to have sound).

This goes for all assignments on this course. So you should discuss it with your tutor, particularly the stand-out element for this project.

What should that be, the stand-out element for this project?

The thought, obviously. Conveyed in the one-line pitch:

Charlotte Smith wakes up one morning with the superpower of knowing what everyone’s mission in life is, except her own.

I’m trying to sneak up on a thought at the moment.

You don’t know how big or small it is at this stage.

You have to go by feel.

There’s a great clip of David Lynch that deals with exactly this. (It will begin lecture 4.)

He says, you need a small idea to catch a big one. That is, you bait your hook with the small idea.

It’s like the big idea is already there. Maybe walking around. Under the surface. In the next room.

If you know his movies this makes complete sense.

The thought I’m trying to get at is not who is Charlotte Smith, but what is Charlotte Smith. In my pitch-line she is a character: that’s the small idea I’m baiting my hook with. ...

Character. Why character?

Lots of answers come to mind to the question Why do we have characters?

I’ll try one out to see I can get a line on my idea out of it.

You’ll notice by now I have a habit of switching from I to you, or from we to you. But Charlotte Smith is quite outside that.

She could be a she. She could be a he. She could be a they. Because one thing’s for sure, Charlotte Smith is not an it.

That is, a character is not an it.

Even where we are not sure of her gender or her preferred pronoun, of what she does in the film, or even if she’s real or fictional, and who’s to say really?

I mean, what is the difference when it comes to character?

Perhaps we can say Charlotte Smith is a role. But it’s definitely different from the role of teacher or parent or student or ... Charlotte Smith might take on any one of these roles, in her day-to-day, and it would make no difference to her ... to what moves her.

So what we are trying to get at is what is behind any of the roles Charlotte Smith might play, even what is behind her name.

Maybe she hates her name. Maybe she’s entirely at odds with her identity.

You get that with characters, sometimes they rebel.

You get that with characters, sometimes they rebel.

Sometimes we do too.

We don’t want to be the person who has to do all the cleaning up for the other people who live in the house.

We don’t want to limit ourselves to the roles life asks us to play. But we do want to be able to choose them.

We want to be able freely to choose. I read the advice of an older writer recently. Asked what advice she would give to younger artists and writers, she said the main thing is to take control of your fertility.

The advice is not the expected advice. It sounds like it’s about life choices but it’s really about what happens when we do not choose, when what we have not chosen for, happens.

The surprise is that this could ever come as a surprise.

...

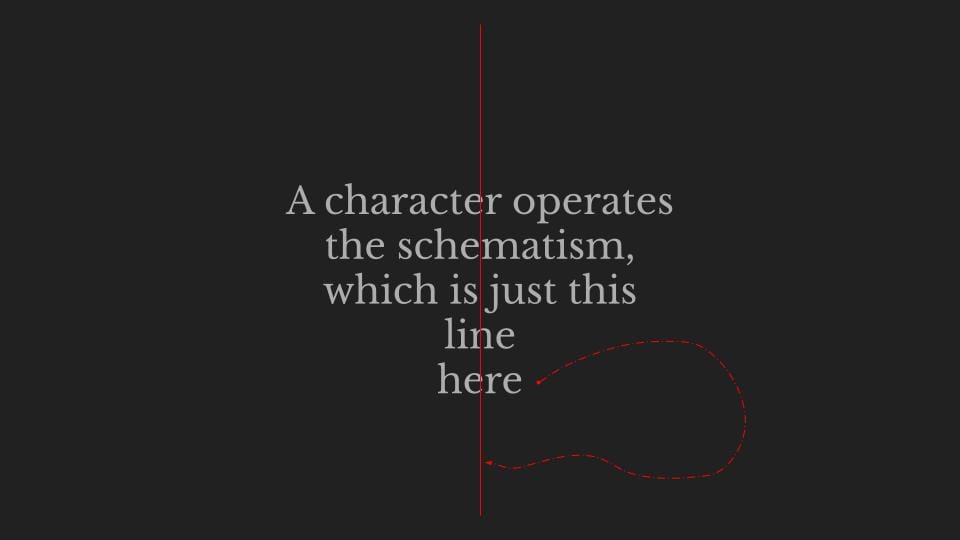

A character operates the schematism between the two sorts of time: the time where we can choose and the time where we cannot.

The time of hesitation, we said earlier, of the gap which prepares us for all the possibilities we face, the time of memory, and that time we cannot choose but that befalls us.

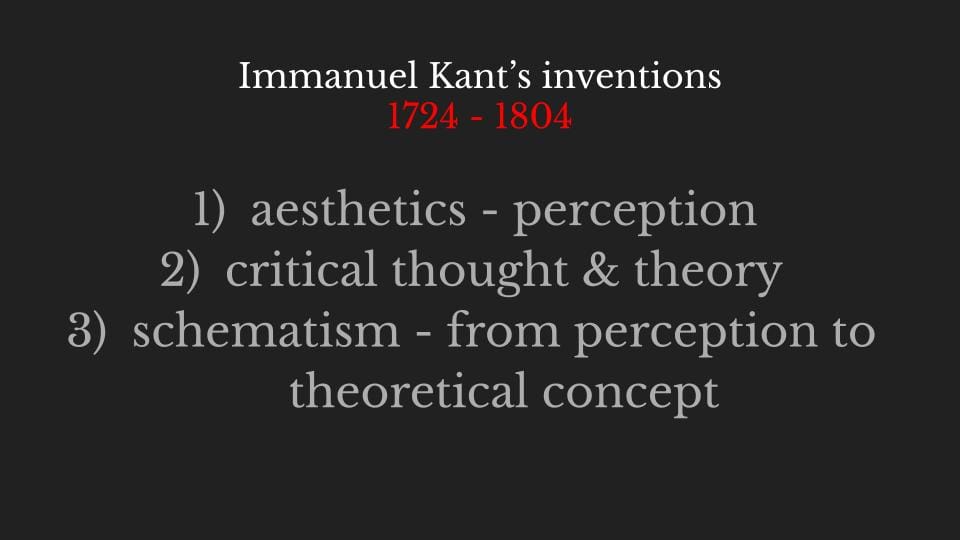

Schematism has a long philosophical legacy, going back to the Enlightenment, to Immanuel Kant’s publication in 1781 of the first in his series of critical philosophy. About which we need only to note three things:

Kant invents the field of aesthetics, which is the field of study we are in; aesthetics comes from the Greek word for perceive.

Kant’s critique says there is no direct correlation between perception and either the inner world or the outer world, and so starts the tradition of critical thinking, which is one that we also participate in here. This tradition questions our habitual assumptions and common associations to get a better idea of how it is that we think what we think.

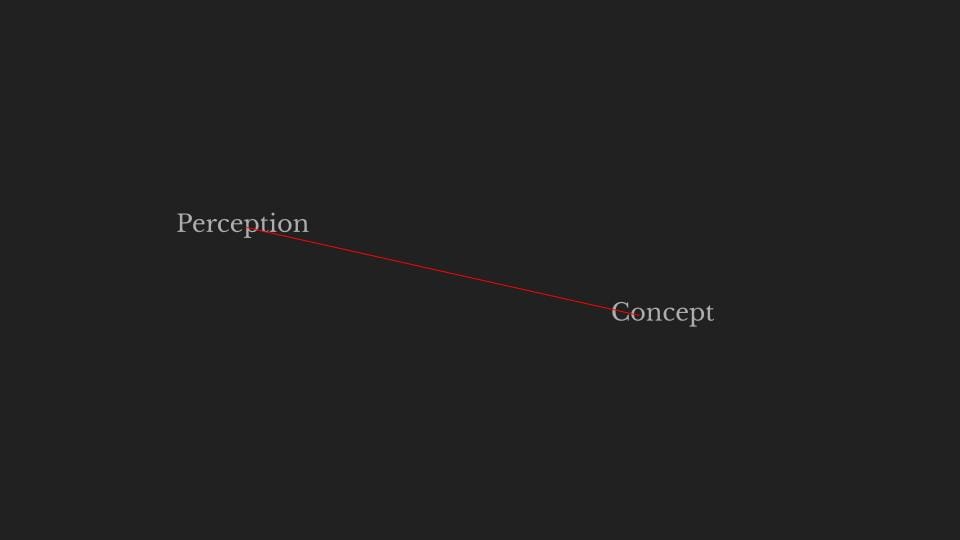

And, most important for us, is to note that for Kant the schematism gets us from what is perceived to the concept. That is, how do we go from perceiving a sensation and having a concept for it? How do we go from perceiving a sensation and having a concept for it when the proof that the concept is true is not found in the perception and not found in direct sensation?

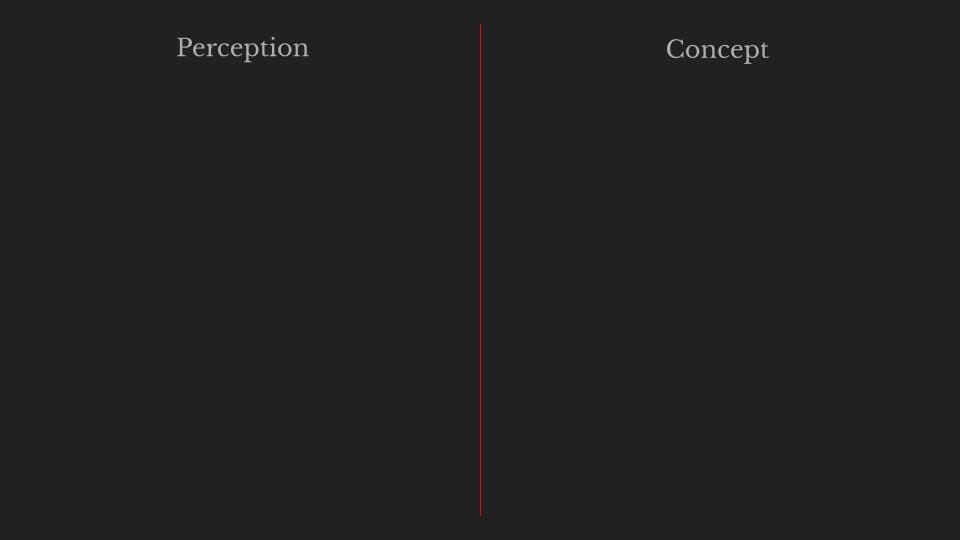

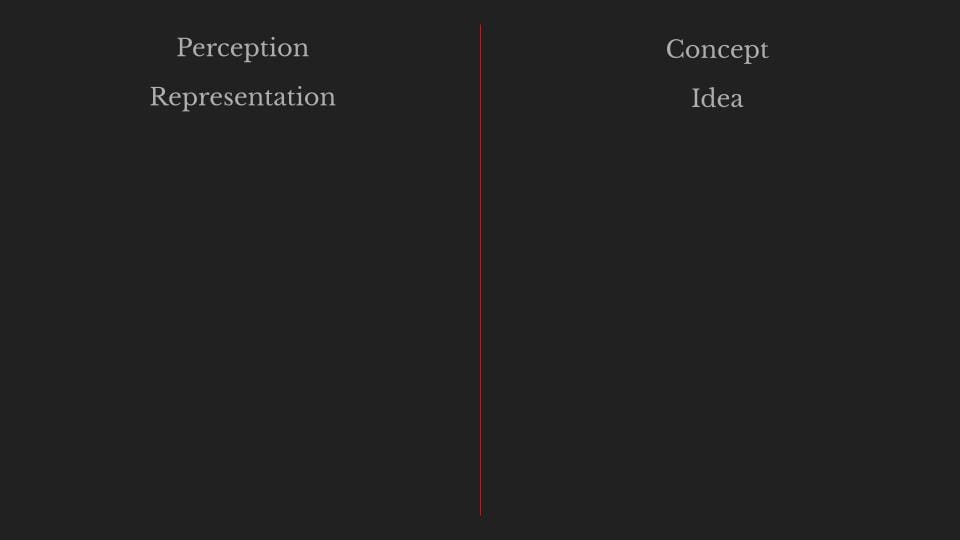

His answer is the schematism. Here it is.

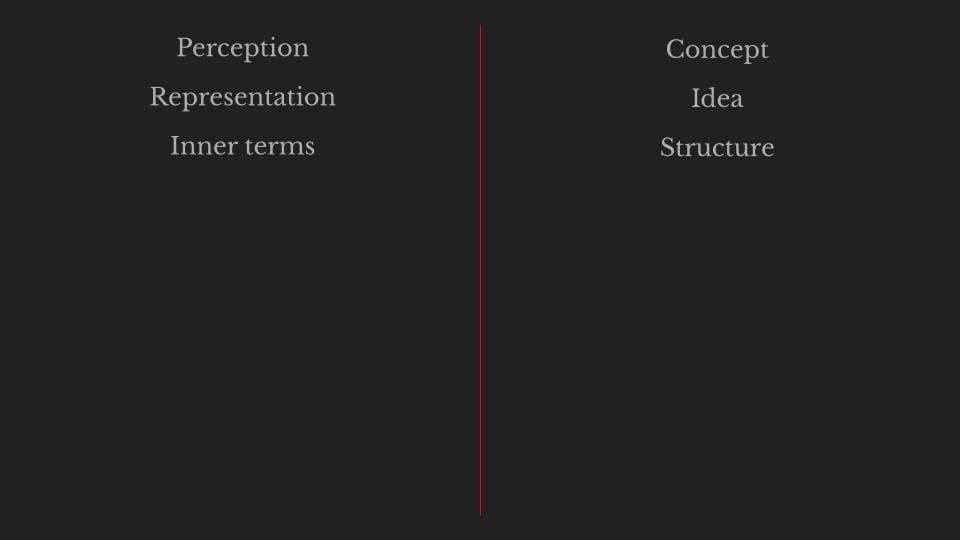

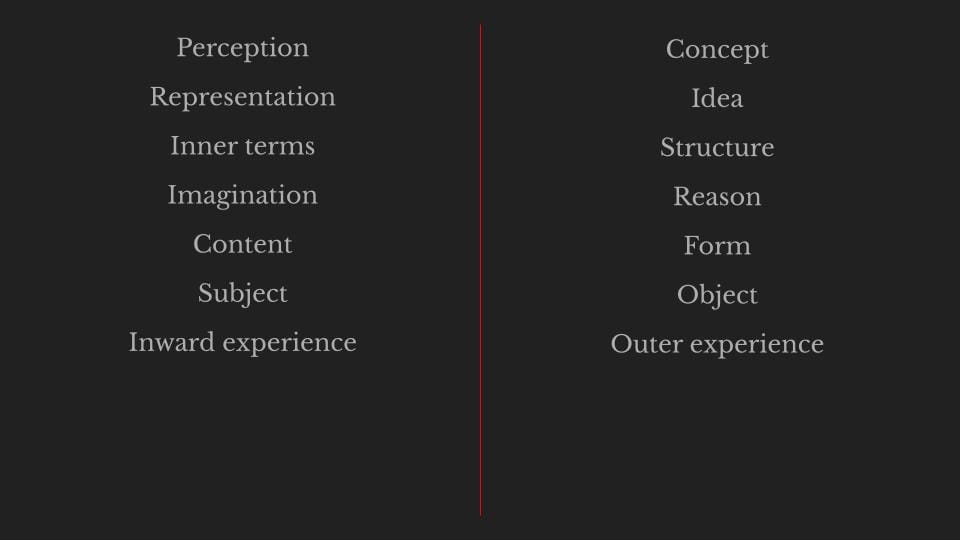

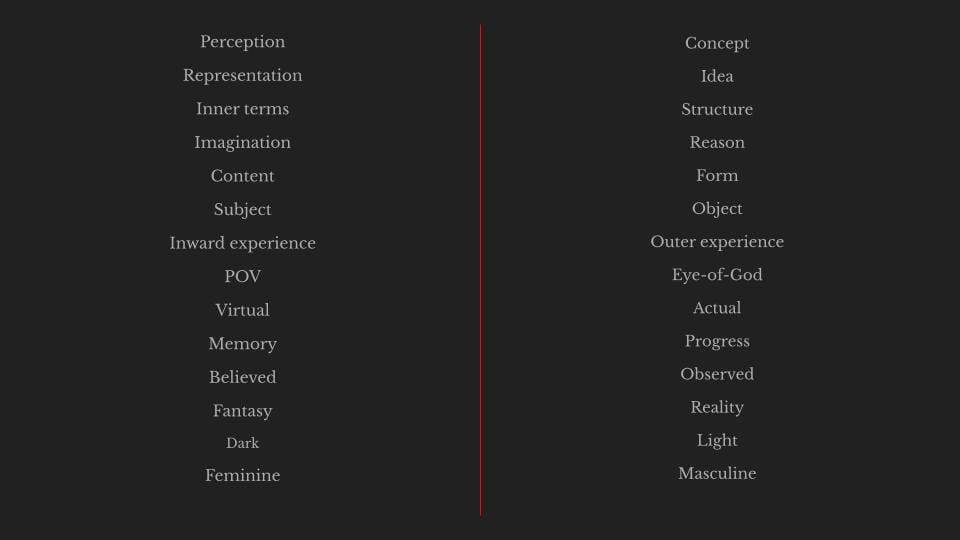

Perception. Concept. And that line inbetween is the schematism that always works and is, he says this, a hidden art. The schematism shows what works but not how it works or what works it. It is like any schematic, like an engineering schematic: it shows us how to put perception and the concept together.

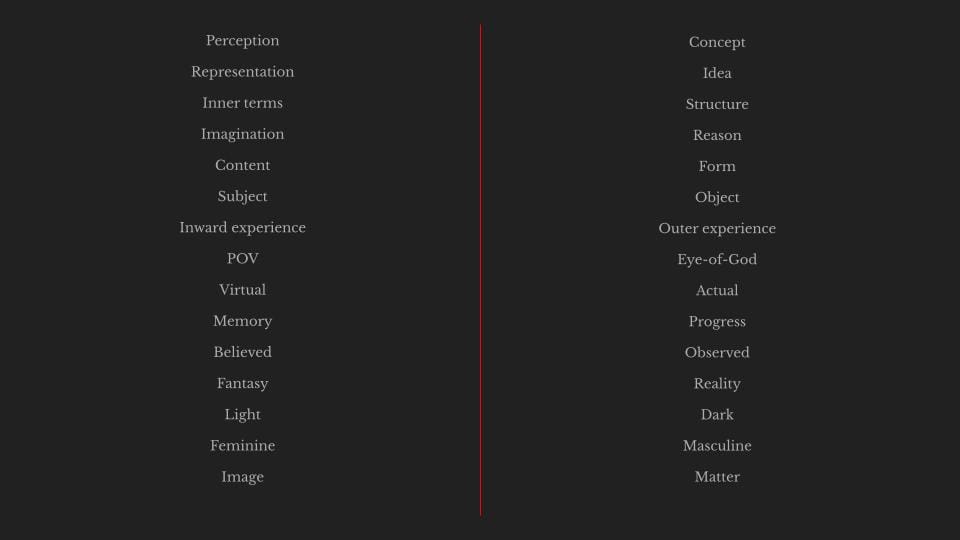

Before moving on, we should pause to look at the schematism:

The critical project since the Enlightenment is to give us a better idea of how we think what we think so that we can think better. So what side of the schematic, what side of the line do you think is favoured?

Concepts of course are better than perceptions since perceptions are often wrong. We are easily enchanted by, for example, the beauty of moving images, for example, Rafik Anadol’s hallucinating machine, and it’s up to the critique to show us how it works and affects us, and so disenchant us. To see...

Wait: Kant shows the critical project to be not goal-less but end-less, because all we perceive is only ever a representation, and never the thing in itself.

Das Ding an Sich. The thing in itself is out of reach of our senses. We can never reach it. So every illusion has to be stripped from our eyes... and even then, the best we can hope for is ... for there to be a harmonious accord between perception and concept. ... So you can see, representation is not opposed to the real thing but we must reach for the higher order of idea, of forming ideas, in ideation. Why? Because God is the guarantor of the whole order. The harmonious composition. We have to assume it. We just have to. We just have to be ... better. God is the transcendental signifier.

Remember “the structure is transcendent to the terms which actualize it”?

And we can start to see that the schematism can take up any binaries that we can throw at it. And that it starts to order them in hierarchical opposition. Otherwise called binary oppositions, where one thing is opposed to the other and organised so that one is just a little bit better, not according to what is in our heads but according to what is in God’s. God’s the guarantor of the organising structure. (See: here structure does not follow from the terms which actualize it; it precedes the terms and determines their order.)

What does the Enlightenment mean? Reason in the highest. Reason or God sifts through and goes, this not that, and organises them.

Concept not perception.

Then outer structure not inner terms.

Not representation, the idea reason forms. So forms over content.

And ‘outer experience’ looks like a reversal until you realise it means outer to our experience. A god’s overview rather than our limited perspective.

And let us not forget...

Image. Matter. Or memory image. Material reality. And so on.

...

Then Bergson comes along and redraws the schematism as a manifold. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Or, maybe. Would it make any sense to say this manifold is put together from the inside?

A character operates the schematism: operates the schematism means how they connect. And when I say we, I mean we as much as any characters.

A character operates the schematism ... which already in Kant is a way of going from one thing to another. And even in Kant does not divide but link, because for Kant the real division is between The Thing in Itself. The Real. The Form. The Idea as it is in God’s head. And all that, for Kant, is definitely, and definitively, in ours.

All a character has to do is express that connection.

Why not, what a character has to do? is express that connection?

Because there is an immediacy here.

Like the stroke of a pen or a brushstroke.

It’s not much but it’s everything.

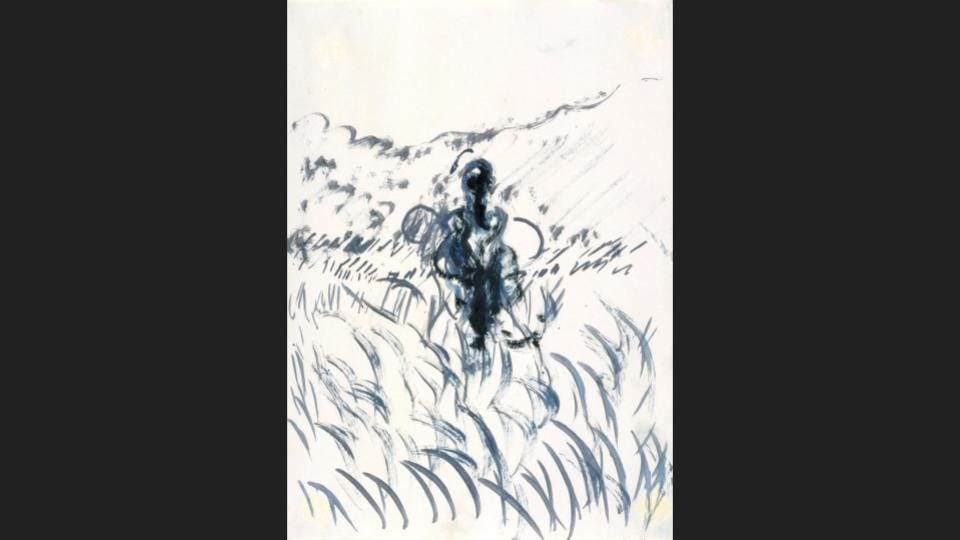

Or think of Chinese art where random strokes suggest an entire landscape. A swirling movement across the paper ... or a single line that is diffused and frays out in the water ...

No, there’s not landscape there, until very deliberately a single downward stroke is made. And a figure leaps forward: there is a character in the landscape.

What was random before, becomes a steep hillside. The line of pigment diffusing in the water becomes an horizon line which our figure is slowly crossing, as if walking into the wind.

Or as here, as I’ve tried to simulate, a figure poling a boat on a still lake…

All a character has to do is express the connection. All a character has to be is schematic.

I think also of how my son used to play. He had other toys, but all he needed and in fact he preferred was to find a twig or small stick that he could animate. And from that twig’s place and style of movement, from its mode or modes, were formed whole worlds, my son could play in and elaborate into further roles for the stick and further worlds to explore.

So we could say the worlds connected are those of interior and exterior life. But that doesn’t do justice to the to the heavy lifting that despite its schematic nature a character does. It’s to focus on the landscapes, which are quite arbitrary, until the character is put in, which then become the landscapes of this particular character.

This is entirely different from saying it’s a matter of perspective.

Why do we have characters? Well, we don’t have characters so much as have recourse to them. We refer to them.

They are points of reference or they animate the points of reference.

These points of reference are those of the conditions of life.

And the conditions of life are those determined in an historical and social milieu. You remember the first concept we introduced? Historicity.

At first you might think historicity to be a prison. We are imprisoned by our perspective. Another word for this has been ideology. It covers a class programme and is a question of the privilege or lack of privilege into which we are born, a determination of our historical and social milieu. But we are not characters... or are we?

This now is the choice between perspectives.

We can say we are imprisoned by the present. Or we can look for other possibilities. Of life, naturally.

And this is why we need characters.

We need characters to express our own connection.

This says more about characters that it does about us.

So, so far so theoretical:

So what does it say about characters?

1) that they are determined in an historical and social milieu.

That they have an ideological background. For example, a feminist character will consider her background as being a programme setting the roles for women from which they want to break free.

What do they do to this background? They make it vibrate in all its details. In the specificity of those details.

Characters animate the historical and social details that determine their background: we can say they have biographies; a psychological make-up; a certain genetic predisposition; they have their social and historically determined roles; for children in the industrial revolution, it’s going to the factory. Factory children.

How are we going to identify with that? This is the question of how do they make vibrate the details of their background, of their world?

They do so by travelling light: characters don’t need biographies, genetics, a knowledge of social history, a place in political economy: or, rather, we don’t need these to create a character. Again, think how little we need: a line, a stick.

A line, a stick, we already have a believable character.

For this to work, all a character has to do is connect. Not to us, the viewer. Connecting to us comes second. It comes after the schematic and explains the schematic nature of character: a character has to express the connection between the two sorts of time: the one of historicity and the one of perspective.

The two sorts are these: memory and history; the determined one of the background and the one where there is a hesitation, where the character has possibilities of action.

When a character does this, we can believe. Identify with. Feel empathy towards. And so on.

2) If this is all a character needs to do a character need only schematise. A character need only be schematic to make the whole background vibrate.

We can see this directly with Studio Ghibli films. The painted backgrounds can have an extraordinary level of detail.

They show a particular time. A place. But the character’s, particularly in their faces, are in comparison sketches. The bare minimum. Eyes. Barely a nose. A mouth. And bodies of some kind. The clothes belong to the determined milieu. But the characters do not. They animate those surroundings with possibility.

And let’s deal with this right up: the question of realism is badly put. Studio Ghibli backgrounds are realistic. But the characters are not. They are possible. We endow them with possibility by seeing their connection.

Then, is this possibility real? It’s absolutely real. It has the reality of possibility. It has this reality without bearing any resemblance. Without being a representation of a given (social and historical) reality. And without the character being a stand-in for the viewer. That is, without analogy.

(This is the point of the phenomenon named as ‘uncanny valley.’ It does not operate by resemblance. The uncanny phenomenon occurs when we feel that a character, a robot, a doll, although it might resemble a living thing does not express the connection between memory, that hesitation to act, and background: it feels wrong and spooky. Like an object pretending. And usually it acts straight away. It is in fact an ‘it.’)

OK. 3) How does this work?

It’s fine to say a character connects the sort of time that involves hesitation, implying a kind of choice, a possibility, but this isn’t what a character does. It is what a character expresses.

The question is, What do characters do?

From it we get the first rule of analysis:

What happens to characters is important.

To analyze something you first have to care about it.

Think about that when you’re next asked to do a formal analysis.

An analysis is no more a description than a character is a resemblance.

I’ll leave that hanging and perhaps we can come back to it.

A character is always engaged in doing something, even if just looking. In fact that can be the most powerful thing a character can do.

What is happening when you see a character looking at themselves in a mirror? They could be thinking about anything. But what you know is that they are thinking. They are in the gap of hesitation. They are operating the schematism, expressing most strongly the connection between the two sorts of time.

They are there most animate, because the background they stand out against is themselves. Their own psychological make-up, their lives, and so on. Outside of the given conditions of life, those which are socially and historically determined. They are animating their own life, or life force, as a field of possibility. This goes further than perspective.

Perspective tends too readily to be reduced to opinion.

Opinion is a poor second to animation.

A character is therefore a vector for action. And, considering the possibilities that animate the background, a vector in phase-space. (Look it up.)

From the first rule of analysis, that allows us to care enough about it to do the analysis, What happens to characters is important,

we get the second rule:

The most important thing about characters is that they don’t know what’s going to happen next.

This is the rule that allows analysis. If we simply describe what happens in a film or movie we don’t give the character their due. Which is due to the fact that they, as operating the schematism between memory and the past, present or future they inhabit, are making decisions every moment.

They don’t know what’s going to happen next.

Charlotte Smith wakes up with a superpower: she knows, just by looking at someone, what their mission in life is.

What does Charlotte Smith do?

She tells them of course.

She says, Your mission in life is to ...

And the reaction she gets leads her to consider her strategy.

So she just suggests.

Still, she meets with resistance if not outright refusal.

Even when their mission in life is good it seems that people just don’t want to hear. What does Charlotte Smith do? She tries to suppress her superpower.

But she can’t. All it takes is to look at someone, and she knows ...

She grows to hate her superpower. She wants it out of her.

And then she meets someone whose mission in life, she knows, is to save the world. How can she tell them the fate of the world lies with them? She tries...

No matter what she does they don’t believe it. They shut her out. They call her crazy. They report her to the authorities.

It’s useless.

Charlotte Smith is destroyed. Remember her pitch line?

Charlotte Smith wakes up one morning with the superpower of knowing what everyone’s mission in life is, except her own.

What’s going to happen? It better happen quickly, Charlotte Smith has only ten frames.

If she can’t tell people, if she can’t tell the one who can save the world that they can, she can show them.

She can dress it up as a possibility. For them to consider.

So it comes to this, Charlotte Smith makes an animated short film with the pitch line,

Charlotte Smith wakes up one morning with the superpower of knowing what everyone’s mission in life is, except her own.