moving image: theory | context: lecture 4

The gap in which there’s a thought. And a character who thinks it.

And to the character belongs a world. Without the character no world. And no structure.

We learnt in the first lecture that structure follows from the terms that actualise it.

So, in a way, we are retracing our steps. Retracing our steps from the moving image to the structure, structures, which it actualises.

And each time we do, because there's more than one structure, we have to be careful we are not imagining things; or, as psychoanalysis might put it, we have to be sure we are not projecting onto the moving image, in one of many of its forms of expression, a structure that is not its but our own. And if not our own, a structure we have been given, or taught.

It could be a structure based on the assumptions of our historicity. And comprise bits and pieces from what is currently in the air that we read into the image. That we in fact super-impose on it.

Assumptions from what we are currently supposed to be thinking. And neither what we think, nor what the image thinks.

The image thinks? we have to come back to that.

The image does not have its own structure: it actualises it.

At least it is not through structures that we encounter it, but through sensation.

And, if it moves us, emotion. But everything starts with sensation. And sometimes we have to ... retrace our steps. To get back to what caught our eye, what engaged us.

The structure will tell us how it works.

It won't tell us, unfortunately, why something works.

The structure we dealt with in the last two lectures was concerned with characters. It told us how characters work.

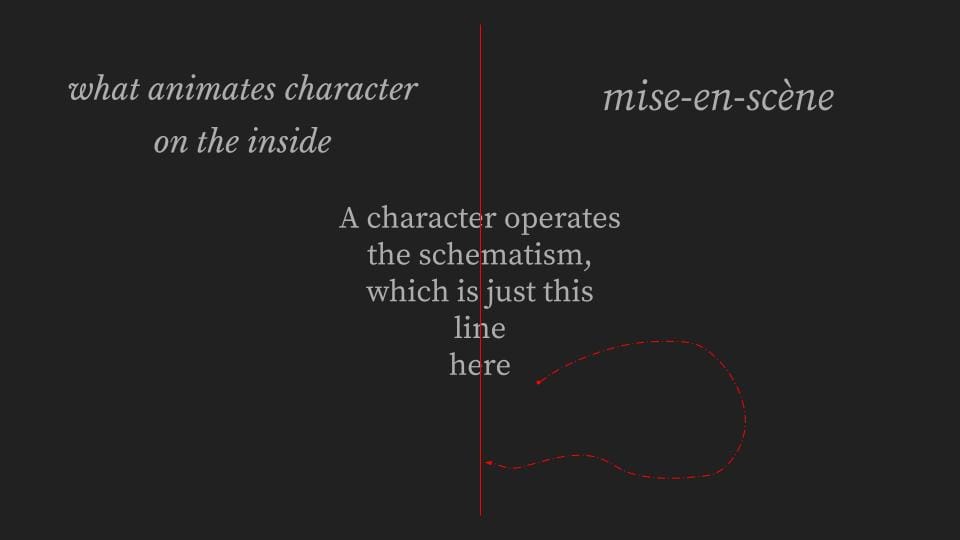

Characters work by providing a link between their inner life, the life that animates them, and the worlds they inhabit, the situations they encounter.

This is the minimum. The minimal condition for character.

Again, psychoanalysis and psychology and psychiatry, and, now, neuro-science, neuro psychology, neuro-cognitive behaviourism, and, even neuro-aesthetics, a growing field of study: these all tell us different.

They follow a different path: they all deal with a minimal condition for character of recognition and identification. And representation.

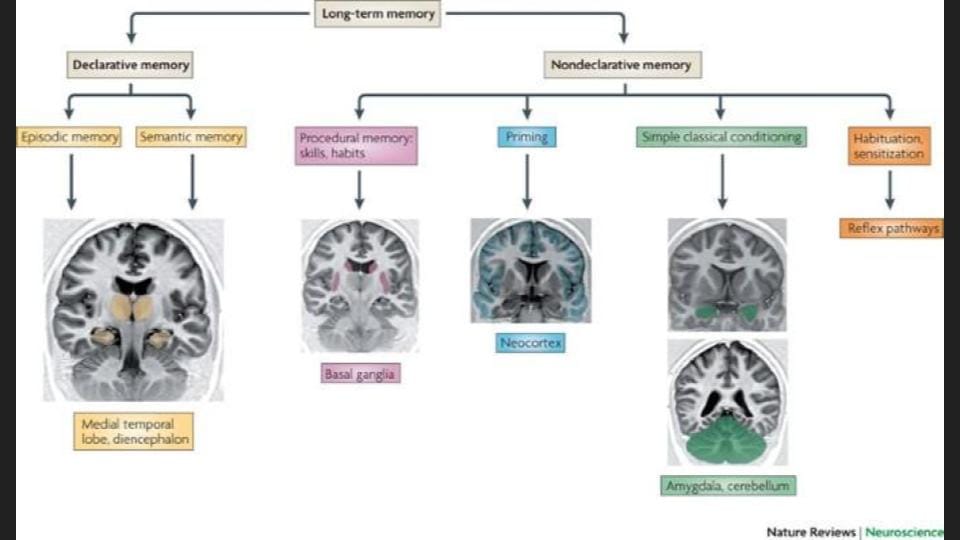

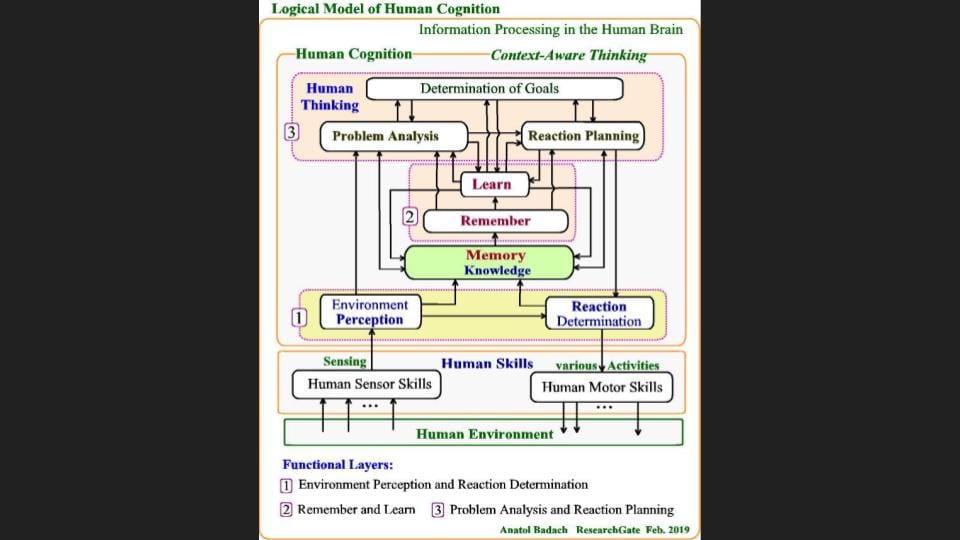

Neuro-biology looks for the places in the brain where the images of memory are stored, for example. And what it assumes is that, when we find where, we will get an idea of how memory works, that is, its structure. But they won't find out what operates this structure.

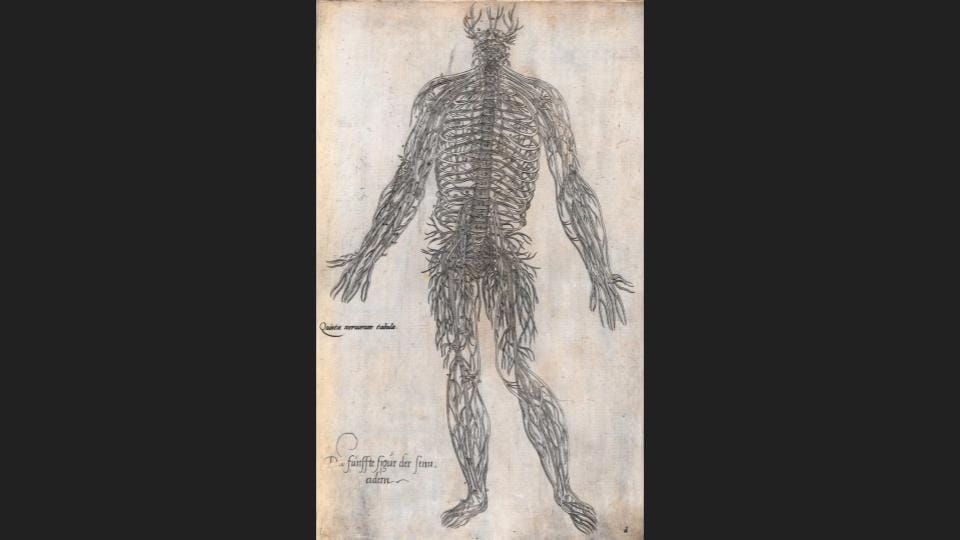

In fact it appears here from this schematic diagramme that the operator of the schematism is the terms themselves.

...

Are they wrong?

Bergson would say, yes, they are wrong. But this simple statement needs to be held up against the context for thinking about these things that Bergson gives us.

We either choose for a view reducing inner experience to what is found in the brain and nerve centres....

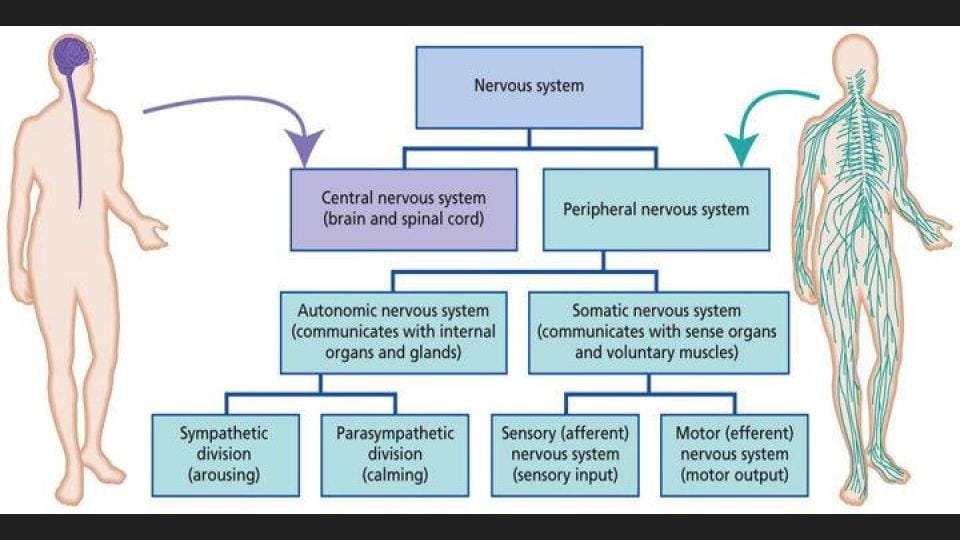

…one of the findings of neuroscience is that a great deal of what it calls 'information processing'

is handled by nerve clumps outside of the central brain (by the peripheral nervous system) ...

the information that is processed comes from perception and only once processed becomes sensation ...

and an identity is sought, or an analogy is sought, so that what is perceived somehow represents the lived world in the inner workings of the nervous system that includes the brain...

We either choose for this view that is current ...

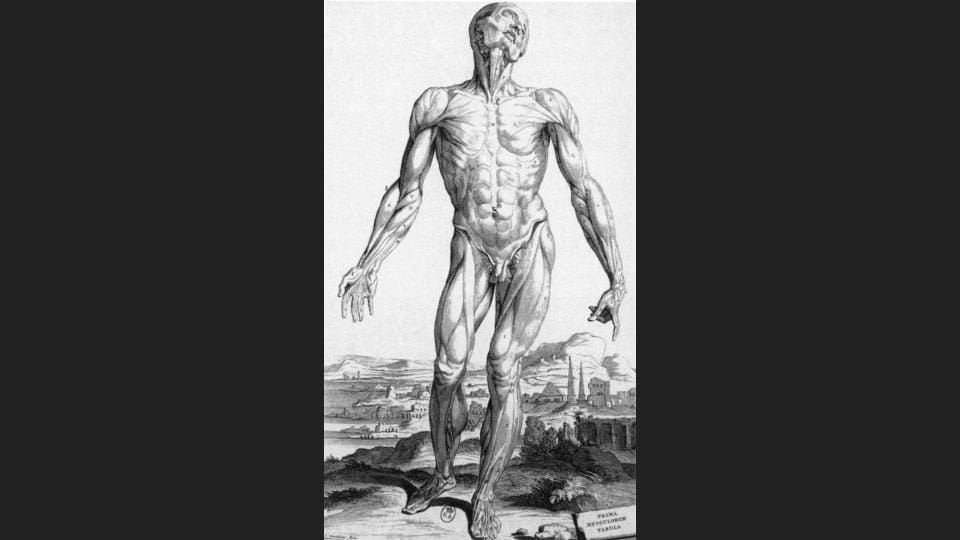

This slide image can’t help but recall another:

What do I mean we have a choice?

Yes. It is one psychoanalysis accounts for by saying there's a deeper level to inner experience, to consciousness, called the unconscious, where I am not myself, but the drives, appetites and desires take me on a wild goose chase which it calls a life.

It is accounted for by neurobiology ... well, it's not really.

So Bergson comes with some advantages: he says the elaborate nervous system and brain mechanism that humans have

allows the playing out of many possibilities in a gap, a pause, a hesitation, before action is taken. Before I commit the next word to paper, and before I read it now to you in this lecture, there's a zone of indeterminacy, where I have the freedom to depart, from the script... in fact, I can get out of this whole situation. I can change my material circumstances, I can go outside.

In fact, this zone of indeterminacy is already a way outside and a way in which I am already free. I am not tied to my impulses if I can find other ways, other possibilities... and other... characters.

The writer, DBC Pierre, it's a pen-name, the DBC stands for 'Dirty But Clean,' whose theory of narrative structure is the reading for next week, DBC Pierre says writing a book is the best place to face your demons.

Where they are out in the open.

In other words, writing, like making images, is a technology that elaborates on our nervous system and brain, on the outside, out in the open, and increases the possibilities we can make recourse to.

Recourse. Funny word. It invokes again the idea of a relay station or a telephone exchange. It also invokes an idea of nonlinearity, the recursion of which feedback and the feedback loop is the popular version.

Where something that happens in the future draws something that is happening now:

like, for instance, the invention of the camera.

It's only obvious after the fact, but think how confused the idea of it was before the different parts came together. It was as improbable as the mind that came up with it that chemical emulsions, clear celluloid, the earliest form of plastic, could be put together with mechanical, physical and electrical forces, in exactly this way: as if the idea preceded the fact.

Of course, the idea was at first only vague that this would turn out OK. It occupied the zone of indeterminacy. Which is not a place but a time. It required a link be made between the world of 'it is what it is' and the inner experience of the inventor.

And that link, as we've been saying is the working-part of a character. It is the reason we can get away with characters that are only schematic. A line and a dot, that seem to be animated from the inside...

We can also see that the idea of a camera before it was made was schematic. Vague. A matter of putting this with this, and now that with that, experimenting, until ... the structure works.

That is, it works recursively. With Bergson, we've been saying where it works, what it has recourse to, in the link the character gives us, is memory.

Where this all happens, as the clip that started this lecture puts it, is in the next room.

It's in the next room that the idea is already whole and complete... if we could just catch it... Or catch up with it... because we can sense it's there. Vaguely. We can feel its pull. And that must mean that we've already sent out a line, a fishing line, baited with this vague sense that it's out there, or in there.

David Lynch could be saying solid ideas come from vague ideas.

Just like Gilles Deleuze who says structures come from the terms which actualise them.

What we're adding here with our theory is the link or the line that connects them. A character is schematic and operates the structure of their connection, which is also a schematism: a kind of diagramme of sensation, of what can only be sensed, before it is perceived. Which, if you think about it, is a reduction. Once the possible structure is actualised it no longer has all these other possibilities.

Once I have all the bits and pieces of my personality and can say, there we go, this is my identity, I have reduced all of the possibilities I have to become different to this handful of really quite petty and on their own quite unimportant parts. I have constrained myself to the idea which is no longer the vague one with which to go fishing in the next room for something better but is the finished item. It is what it is. Like you see on the label. What you see is what you get.

I think Bergson is closer to the reality or gives a less demeaning and reductive view of this reality than that given in the 'hard' sciences. Freud worked his whole life to give psychoanalysis the status of a science. So I choose for Bergson. For his theory.

And me choosing means you can too. You can choose for the way of thinking you like. And know that by choosing for it you affirm it.

And this is true in practice and in theory: if you make an image in a particular way, you are choosing to affirm it. This is as good a reason as any to stop right there and think about it.

…

So. To the structure that the given world has without which there is no character, because without a given world to link to the zone of indeterminacy the character embodies, no character, no-body.

What mise-en-scène tells us is that it has to be put there. Mise, put. In actual fact, mise is to have been put. Still, it's something we have to make. It is a construction.

And from what has been brought together in the scene, we can see the structure. The structure follows.

And also, by constructing it, we have chosen for it, are affirming it, and choose to reduce the world of possibilities to just this one world. We choose what goes into it. And if, when we have finished, it is not, if it is vague in any way, we might want to ... retrace our steps. Or go outside entirely and try in the next room where it is already finished and whole and complete.

Notice there is here a formal constraint: it's not a question of keeping everything in the zone of indeterminacy. It's a matter of a reduction also, like the one automatically worked by perception that reduces what we perceive to what interests us.

When we look at the finished mise-en-scène we want to be able to see a complete, whole, finished, solid idea. Or image.

It needs to ring true. Not give just some vague indication of tone.

And this is the case with the one whole and complete idea of your short film brief: that it is one, that all the parts, the ten frames, come together, yes; but that they have to limit their own possibility, willingly, to this not-vague one thing. One thought. One image made up of a number of them.

The other term for this is 'structural unity' or 'integrity.'

Integration is the constraint, when making a world, or having an idea.

And notice this word structure again. Structural unity or integrity.

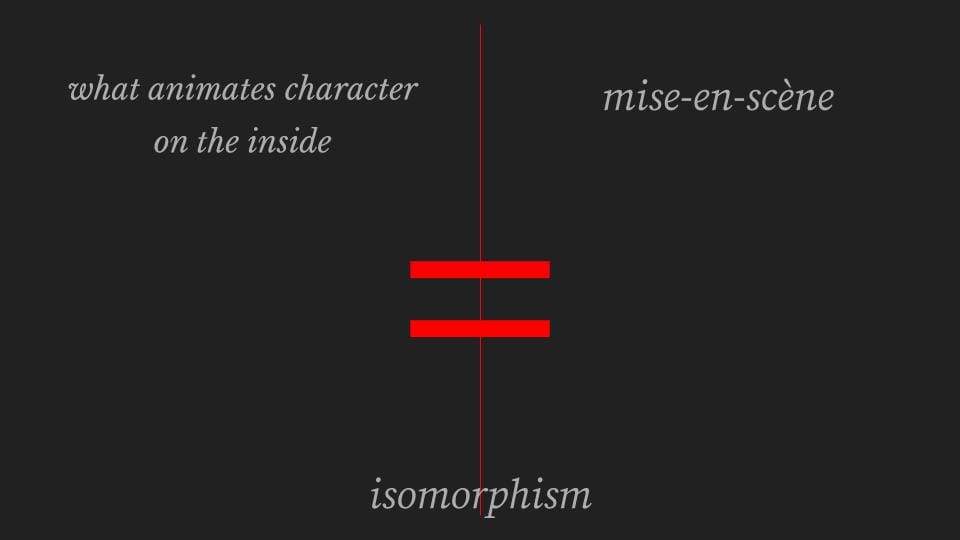

Saying structural identity would not make sense, but this is what is demanded of the mind by neuro-biology: an isomorphism between the world as it is given, it is what it is, and the inner experience of the mind or mental life. Isomorphism means same structure.

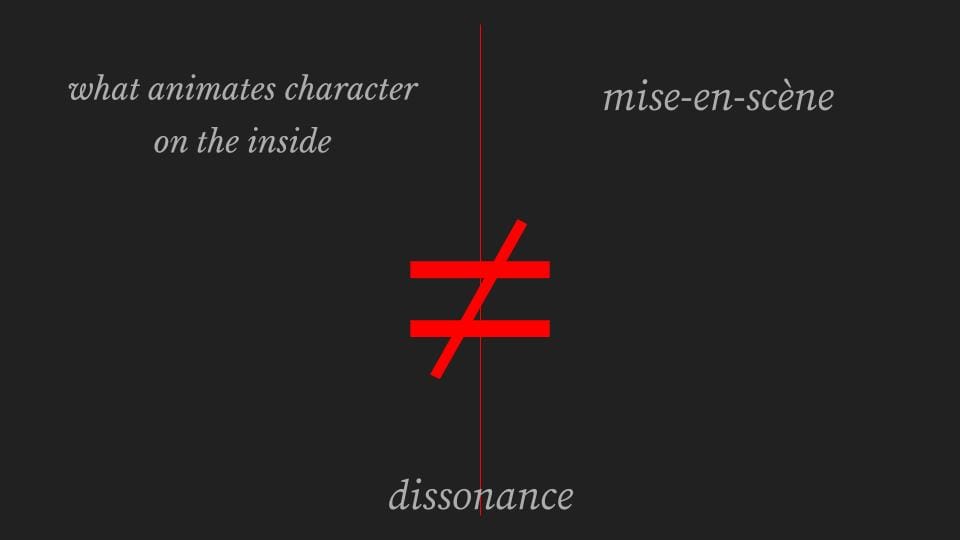

I am saying here there are two structures and they are linked by character: on one side whatever animates the character from the inside; on the other the mise-en-scène.

A short aside: why does neuro-biology demand identity between mental life and world? It's more the case that it inherits from medical psychology the idea if there is a dissimilarity in structure between mental life and world something is wrong.

What is called 'psychic (or cognitive) dissonance' is its mildest form. Which it tries to explain.

Mental well-being is supposed to mean that our inner image of what the world is is an accurate one. This is to impose a massive formal constraint.

We are supposed to be realistic.

For a character being realistic means there is nothing to link to going on on the inside. Because the structure of the world and mise-en-scène matches the structure of the inside world.

It makes the character appear inanimate. Or, best possible scenario, it makes the character appear badly animated, as this clip from Snow White shows, where Snow White was modelled on a live actor while the dwarves and all of the mise-en-scène are ... totally unrealistic.

- Snow White, 1937

Life cannot flow between the mise-en-scène made of cartoonish elements and the very unschematic Snow White because of her ... realistic-ness.

I don't say 'realism.' Realism is a concept, while the technical aspects of 'realism,' so that what is perceived is a consistent reality, are relative.

Relative to the world she is in, Snow White, so conceived to be realistic, expresses its opposite.

While the opposite concept of realism that her badly animated representation expresses is not a mismatch between inner and outer worlds but in the 'matter' of the mise-en-scène, which Snow White in a way sinks into: she sinks into the matter of the scene for being too material and not animate enough. That is, if we go back to our thinking on character, on its minimal condition, the character of Snow White does not operate the schematism by which we get from one sort of time, the time of ‘it is what it is,’ to the other, time as it is, inwardly, the loops and so on.

We can see this in live actors too: when they are wooden. And there too they are more wooden than the furniture. Yet they stick out. You could say, all they show is what they are supposed to be doing.

Then, if they are thinking too much, there is no connection either. This is what Robert Bresson is saying.

Plonk a character in the mise-en-scène, they are the minimal condition for having a character, a model. And not, his point, character’s psychologising opposite, an actor, as was then common in the psychological theatre.

Before moving images appeal to us through character, characters who express that their inner reality differs from the world where they find themselves, from the mise en-scène, that is, who have psychic dissonance... Before character makes an appeal to us at all, the mise-en-scène makes a direct appeal to our senses.

We don't get to choose it. We get to choose how we orientate ourselves towards it.

And sometimes, yes, it can hit us with a force that overwhelms our attempts to think about ourselves in relation to it. Or to process it.

Although I think this 'processing' has determinants that come from the material world and memory, which each of us links to in different ways. There is a zone of indeterminacy.

What overwhelms one person, coming from an experience on-screen or off, strikes another as clunky or schlocky. They say to you, I can't believe you fell for that! that you were frightened, or cried, or had to turn away, or felt like you were on the downhill of a rollercoaster, with sensory overload. While they saw it all coming.

So, before we get to processing character, we process or are in the process of mise-en scène. Mise-en-scène makes an appeal directly to the senses. First.

We are in the process because we link what the moving image shows to what we know in our minds, memory.

The overwhelm is what exceeds this.

So what are the senses mise-en-scène, as everything put in the scene, makes direct appeal to... before we make indirect recourse to memory and our own inner zone of indeterminacy, which is actually on the outside, in the perception itself...?

Touch. Taste. Sight. Hearing. And smell.

There is another sense that Kant, you remember him? from the second lecture, makes great recourse to: apperception, but this is already a loop through our inner lives. It means attending to what we are attending to, or inward perception.

For ourselves as much as for characters.

And it is by way of apperception that can talk about the sense of the sense, for example, how, although we don't touch, taste or smell what we experience in the moving image, it can fire up our sense of smell. Spark it through images.

So that we have an inside sense of the outside sense, a sensation from the perception. …

Touch is the same: although we will get to that...

And it might be thought strange, because isn't it the case that we have really to think about it before we recognise as reeking that reeky decaying house onscreen, all that decaying food in the fridge, all those decaying bodies on the second floor, half eaten by rabid dogs, who have crapped everywhere... isn't it the case ...

…but we can't consciously keep up with a sensory onslaught of... images. True onscreen, as off.

That we can't, means before. Before we get a chance to think about it.

We are always retracing our steps to get a feel for what the mise-en-scène makes its direct appeal to. We are there, in the scene, it arrived in the cut, before we know it. ... hovering over the remains of a rabid dog's dinner.

...

Because it's before mise-en-scène invokes this word, architecture.

Archi means it comes first. It's there before we are. It's there before us and before any character. Of course, it demands our character to be made sense of...

We have to come to terms with everything put in the scene. No. It strikes us that way. But we are always making a selection. Unless overwhelmed by the force of the imagery.

Architecture is a first science when it comes to how we feel.

Think about that next time you go for a walk in the city.

Or think about how much of your current mise-en-scène has been chosen by you?

How much is what has been chosen by you simply decoration, decorating the space, a room of a certain size... a space with a certain atmosphere.

Perhaps you've brought into the room nothing but yourself. Then, consider your clothes. Jewellery. Tattoos. Hairstyle. Adorning the architecture of what you've given by birth.

Consider all those programmes that make people so happy just by making them look good, style tips. They are really happy. Not faking it. When they look at themselves and say, Man, I'm looking good!

... but the architecture precedes the dressing. In the case of mise-en-scène, for the moving image, the architecture is every sensory effect. Even the lighting. As we saw in the expressionist cinema of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920

You might say, what's there in the architecture is only a suggestion. What's there is only in the moving image sequence, what's put in to the mise-en-scène, is what we see. And what we hear. The idea of synaesthesia is purely subjective. Not objectively there. But is this really the case? Is it really the case when so much goes into the scene to fire an involuntary reaction?

In other words, advertising leads us to feel a certain way through suggestion, often through appeal to instincts and drives, importantly sex sells. But is it its suggestion that sells, or does sex make its appeal directly, by by-passing our conscious minds?

Isn't that an involuntary reaction? And shouldn't we ignore whatever is involuntary? subjective, that comes directly onto our senses, all those feelings we didn't choose?

This aspect of ignoring the sensual, subjective, the actual inner terms of the image and moving image sequence, re-organises our earlier schematic, affirming light over dark, masculine over feminine, and taking on all the assumptions that we ought to be questioning.

Bergson’s whole point is if you feel it it’s real.

We have friends to correct our oddities of perception—or to gaslight us: yes, of course you felt that. It wasn’t in the image, but you felt it. Because you’re … at best a very sensual person in contact with your feelings … at worst led by your emotions and prone to crazy outbursts and rants. What is, at best a personality quirk, at worst is a pathology. And not good for my, your, our, and so on, mental well-being.

Nonsense. Psychic (or cognitive) dissonance is the minimal condition of being alive on the inside.

...

That Bergson says if you feel it it’s real is the reason he is sometimes called a phenomenologist.

A phenomenologist, phenomenology, does not proceed from assumption but from paying as close attention as possible to sensation.

phenomena. …

Note, Kant contrasts phenomena, appearances, with noumena, which are the product of reason and judgement. Rational. Good measure. That second less profound loop through the time of memory. The thought police. Not getting to the juice of things, or their aesthetic, sensuous appreciation.

Did you see that the favouring of what is rational is based on the assumption that it is better? So it reintroduces an assumption just when we want not to. Its demands are that we submit to the thought police. And repeat after them, What we feel is not real.

…

My friend and favourite phenomenologist, Alphonso Lingis, inverts the formula that what we sense is not real and not true.

He says that the apparitions something throws up, its projections, and halos, its emanations and auras, its scintillations in the air, its sparkles, doubles and reflections… He says that its subjective effects tell us the thing is real. They are a part of its information. In its affect is its effect.

The virtual components of objects and subjects tell us they are actual.

What is only appearance is always a clue to what is there. And, in the case of mise-en scène, of what is put there.

What is put there is put there is for the sake of suggestion. So we had better, in our analysis, take seriously the claims it makes on our attention. That is, we better take seriously suggestions. What we actually perceive. And in what sense we do.

We have in these lectures been proceeding like phenomenologists, to get behind the assumptions we have about moving images, to think critically.

Not to get behind appearances, but exactly to take them seriously. What is the inner life of a character? A suggestion. This suggestion is all the character need make, the character’s minimal condition. Its soul or anima, which is where the word comes from.

The principle of animation means giving a soul, spirit, or inner life. Which our phenomenological approach here says it’s all a character needs to do, for it to be a subject.

…

So how should we think about the smell of a scene? We should think about it as what the scene is put together to have. We should consider it to be what is expressed by the mise-en-scène.

And what are the terms actualising smell in the scene?

We can wait for the reaction of the character. Say in this famous shot from Battleship Potemkin…

What this shot shows, for Gilles Deleuze, whom we have met before, is a possible world. The world where such violence is possible is what we feel from the face reacting to it.

…

In the morgue, we have the characters violently retching… But this is to put the character before the architecture that comes before, and is a first science when it comes to how we feel.

Anyway, do the characters’ reactions really lead us by way of the sense of smell? Or aren’t we earlier intrigued by their weakness? I mean, she’s a cop. She should be used to that stink by now.

Intrigued by her weakness, we link it to what is subjective for her. It’s not there in the impression made by the scene. The mise-en-scène.

Morgue scenes never work for me as smelly scenes. Perry Mason, the new HBO show, which is a study in mise-en-scène, beautifully designed and put together. Great music. Perry Mason has a great morgue scene. And in it the morgue is old style. There’s blood and guts on the table. But nothing in the air.

A morgue tends to have no atmosphere. And in regard to my own sensation, what fires up my sense of smell is the gaseous. The gaseous apparition.

Which is why Blade Runner strikes me as very smelly film.

Now also consider the meaning of this word, atmos. Outside the context of the aesthetic study of moving images, or the making of them, atmosphere means mood.

In this context, atmos refers to sound.

In New Zealand, years ago, a whole department of National Radio made radio drama. So a whole studio was devoted to atmos. It had gravel paths. It had half a car, for the sound of shutting car doors, and the rubbery kinds of seals the doors have. It had doorbells and all the elements of foley.

What happened? Cost-cutting.

Studio no longer needed, what radio drama was going to be made was going to have foley, sound effects, atmos, added after. In post, we’d say of film, TV and video. Post production.

But it wasn’t added after. And if you listen to what currently goes for radio drama, there’s no atmos. Doorbells, alarms, crunching feet, adequate foley, yes. But no atmos. The sound of … architecture. How in a restaurant there’s the burble of voices, that sounds different depending on how the room’s decorated. More soft furnishings, less sound deflection. Less live-ness to the sound. More hard surfaces, a very live sound.

In any space the characters might find themselves, there would be an atmos, which today is no longer there.

What’s missing is a key element of the mise-en-scène. Its architecture. Its mood.

Now, in moving image land, atmos is taken, often by sound pickup, to be added in post. But it is as essential as the visual elements. After the dialogue take, sound might ask for silence, to grab a minute or two of atmos, to patch over where it’s missing. Or to create a foreshadowing effect in the cut. So that the audience (from the same word as audible, the hearers) anticipate the mood of the next scene, they hear the atmos, before the visual cut, or after the cut. Audiences for films, TV and video often don’t actively hear it, but it creates the mood. And it’s essential. So listen next time.

Yes. It’s a subjective art. And where we are headed with this word that we are equating mise-en-scène with, architecture, along with the archi- is the -tecture, because it suggests the most important word in mise-en-scène. Texture.

Atmos for sound, is a texture, a sound texture. Suffusing the scene with a mood. What about for the other senses?

We’ll already evoked the gaseous for smell. And we have to add it to our scene with the decaying corpses, the rabid dogs and the crap everywhere, a thickness in the air which denotes smell, making us feel the air is thick with the stink. Vile. Putrid.

Because it effects the light, the gaseous used onset is usually called medium. …

Before moving on from sound, we should say sound atmos is diegetic. Soundtrack is different. And is what we tend to listen out for and to notice, even when the soundtrack is inside the audio atmos of the scene. This is a trick, to help the consistency of scenes with music, with music’s tendency to dominate, and demand an emotional response.

With the music or the soundtrack embedded in the atmos, the mood of the scene is continuous. Seamless. Has a single idea. A sensuous idea.

You should pause before adding music. Because it’s such an obvious thing. And in your own work, see, or listen, to what can be done with diegetic elements and audio atmospheres.

- Blue Velvet, 1986

Composer John Cage famously dissolved the boundary between atmos, environmental sound, or noise, and music. He wanted to say that the environment itself deserves the attention of our sense of hearing. That we should actively listen to it, not wait for it to make its appeal in a way that we already recognise, as noise organised into rhythms, melodies and the tones and appeals of speech.

And this is an important lesson. What tends to be missing from music is what places us in the scene. Music is rather a way of relating us to what is in the scene. It has its own perspective. It doesn’t just add a dimension, as we can say the textures of atmos or diegetic sound do. And David Lynch’s work is as textured and rich in its sound environments as it is in its visual environments, so that mise-en-scène in that work cannot be considered without sound…

The addition of music, whether played from a source in the scene, like a car-radio, introduces what is more like a character, the character of the song, the piece played, or the composer. It can go very wrong because it is either an opinion or an animation.

Music comments on the scene. Or it sets details, for example historical details, in vibration. As commentary, it is always too much, telling us what to think or feel. As character, embedded in what we have been calling the historicity of the scene, it can be great. It can say, this is the 1930s, as in the series Perry Mason. Or, famously, as we saw with Kubrick, whose use of music is exemplary, it offers a juxtaposition, that with regard to any element in the mise-en-scène we call anachronistic.

Like a machine gun in the film Jesus Christ Superstar.

- Jesus Christ Superstar, 1973

The use of anachronistic elements is theatrical: it heightens the scene … but the base level of scenic consistency has to be there. We also know from our reading of Bergson that we can say that the theatrical use of anachronism in mise-en-scène has the effect of a slight shock… it breaks us out of an easy relation of recognition with the scene… and sends us into a longer memory loop. We look in memory for what makes sense of the choice of The Blue Danube or the machine gun. Or scaffolding. We operate the relays or the telephone exchange…

The level of anachronism we’ve become used to is in dialogue, in the use of swear words in historical periods where these words would not have been used.

For example, in the series about the writer Emily Dickinson…

- Dickinson, 2019

The purpose of this anachronism is all too obvious: to make us hip to Emily’s jive. To make her seem not like a victim of her own place in history, but to show her as free to make her own choices, so we relate to her now.

In terms of the understanding we’ve formed here on character, you could say this series takes place entirely in Dickinson’s inner experience, of which the outer historical reality is just a projection. … Or you might reject it as misspent effort to make her relatable.

Mise-en-scène is the structuring of a scene’s sensuous appeal. That mise-en-scène is the structuring of a scene’s sensuous appeal does not mean that we should like it. But that it already appeals directly to the senses.

So that mise-en-scène involves the careful building up of sensuous dimensions, including the dimensions of space.

Why space? Because the screen image is flat. And in most cases it is monocular. The camera usually has only one eye and the digital sensor like physical film is flat. In both cases effort has to go in to creating the illusion of three-dimensionality.

For mise-en-scène this effort is in layering texture. Without texture, no sensuous dimensions.

As we are showing, this goes for all the senses. For mise-en-scène senses are dimensions.

A 3D digital mise-en-scène engages this effort at sensuous dimensionality as much as that of a nature film shot outdoors.

In both cases, mise-en-scène is about texturing the shot, using in-camera techniques, like optical lenses, different focal points, and so on, as well as dressing in or adding physical elements of texture. In fact, the efforts that go into sensuous dimensionality are greater in the case of digital media than in film.

This is the meaning hidden in the lists of SFX and VFX artists at the end of any blockbuster, from digital designers, to modellers, compositors, and, of course, those whose job is precisely on the surfaces in shot, the texture artists, digital scenic artists, those whose job on a physically realised set is to add texture, stippling and shading surfaces, adding grime and dirt, or rust, aging surfaces to show, where it is needed, the effects of time.

Alien was exemplary in this regard, for not showing a pristine high-tech interior, but a physical space occupied by bodies. Grease marks and possibly food stains on the seats, grime on the tabletops and touched surfaces.

To give what impression? And we must also link this sensuous regard for the mise-en-scène with what happens to the characters.

Because character is an element of design.

In other words, the fact of the femininity of the protagonist, although nontraditional, works into those lists we formed in the last lecture, where a conventional association exists between sensation, femaleness, base materiality and subjectivity.

Male-dominated scifi wasn’t so interested in bodily functions in space.

...

Mise-en-scène creates a sensuous idea by giving a texture, a sensuous narrative, for the eye to follow. The eye, yes, but not above all.

Above all comes what is touching. And what moves us… in both the sense of e-motion and of action, the action of touching, and reacting to the tactile, preparing us for the possibilities of action… enacting those hesitations we have been talking about.

Now, this is where you must object. Sight is as far removed from touch as … dark from light. (Again recall the binary opposition: Enlightenment and the Dark Ages.) But is it?

What about the texture of shadows? And all the different darknesses? All the different varieties of light?

Diffuse, light in smoke. With dense shadows.

Exterior darkness.

Interior darkness. In a close room. In, as we said, camera.

Or outside. In the forest. Walking with our hands outstretched. Expecting any time to … come in contact with a surface, hoping it’s not the skin of somebody who’s been lying in wait for us. Who’s watching. Hunting. Hungry.

…

The way visual images strike the sense of touch, the way they strike the tactile image, is called the haptic. It is a matter of texture.

And it is also a matter of apperception, of the way we sense what perceive... of there being a gap between perception, which is a selection, and sensation, a gap where, if we are not paying attention to it, as we generally are not, a motoric or motor sensory association occurs. It takes us simply from what looks rough to what feels rough, rough to touch.

From what is slimy to what slips through our fingers.

From gases to smells. That is, seeing gases provokes an olfactory sensation. We don’t need to smell the gas to smell it.

When the cues are obvious in the mise-en-scène is when we notice it and noticing it usually breaks the circuit, the circuit or circle of habit.

This is the case when we notice the music telling us the scene is sad.

Or when the colour red all over the mise-en-scène is clunkily trying to tell us, Here is Passion!

Then what we feel is ... the world is not believable and the direct appeal to the senses has failed.

And this is the case when we see the actors overacting, over-emoting, going from sensation to its cheap cousin, sentiment. It explains why we link over-the-top acting with chewing the scenery. And underwhelming acting with being as wooden as the furniture.

In both cases we make a link between character and the mise-en-scène.

And this goes for the mise-en-scène itself. It either works, is the thing in itself. Das Ding an sich. Or does not. Is too much or too little.

According, we have to remind ourselves, to our historical conditions. So The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is over-the-top.

But Le samourai still stands up.

- Le samourai (dir. Jean-Pierre Melville!) (1967)

What touches us is of course different to this. It feels supersensory, beyond the simple senses of sight, hearing, smell, touch and taste. And is the most subjective.

That is, it goes to our own character. It operates the link between ourselves, what is in the mise-en-scène and how the character relates to it.

Today we know it to be manipulable. Which accounts for how dated pre-Second World War moving images can seem. In other words, unless emotional manipulation is subtle, we notice it. And it breaks the spell.

So advertising... and this applies to all media... all use techniques to convince us of their story. These go from sensory cues to social nudges.

From what is in the shot to star-rating systems and the recommendations of strangers and friends. Do we need to worry about that here? No.

It’s usual to want to buy in to the dream. And common to want to work in the dream factory that digital media is. And... the sense that we have so far been neglecting... we might even develop a taste for it.

...

Taste, the most subjective, that focuses on our bodily chemistry, but that goes all the way out to social groups who like the same things. Who share the same tastes.

Taste goes all the way from chocolate to social organisation.

Where is it in the mise-en-scène?

Tied up with the other senses, of course. With sight, and smell, and touch, and sound, but taste operates that sensory-motor circuit that we pay least attention to. Perhaps we think it’s all body chemistry. So our habits of taste are genetically determined.

Or do we begin to consider habits of taste like any other habits? As being historically, socially and economically formed.

This is where our discussion of mise-en-scène and character can help as well, by opening a gap in our processing of sensory data and their sensation, going from recognition, to attending to how these habits are formed, yes. But also to experimenting with our sense of taste. Seeing things we don’t like. Not to broaden our sense of taste but to find new possibilities, new sensuous possibilities, for life.