moving image: theory | context: lecture 5

Welcome! ...

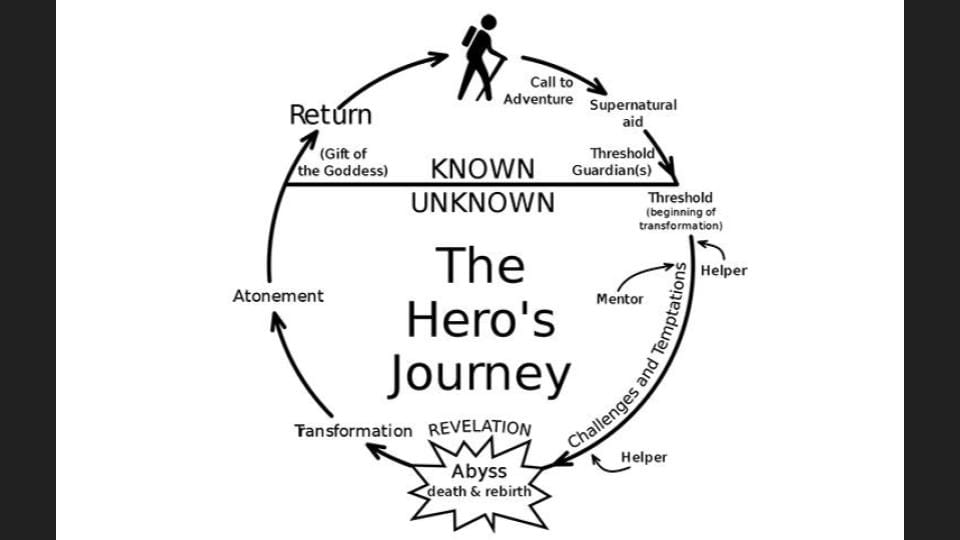

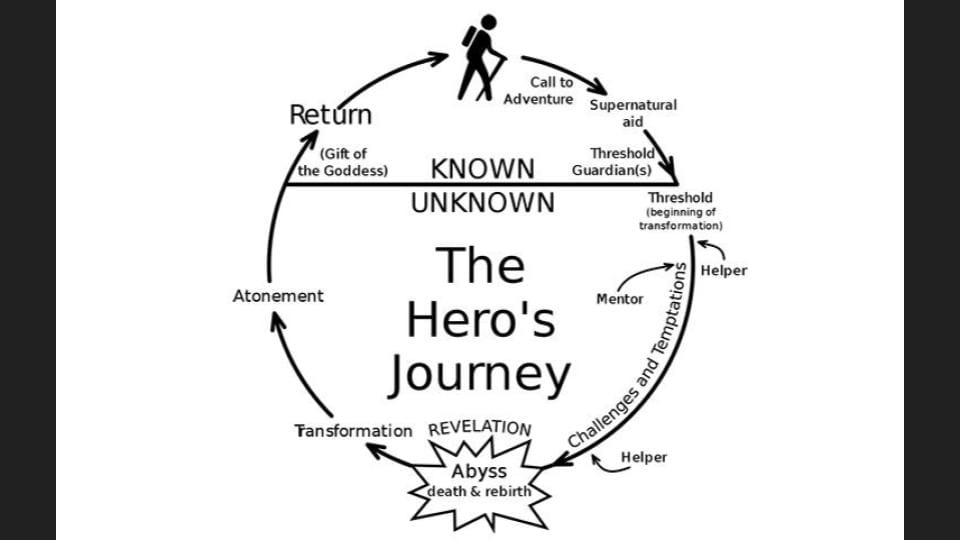

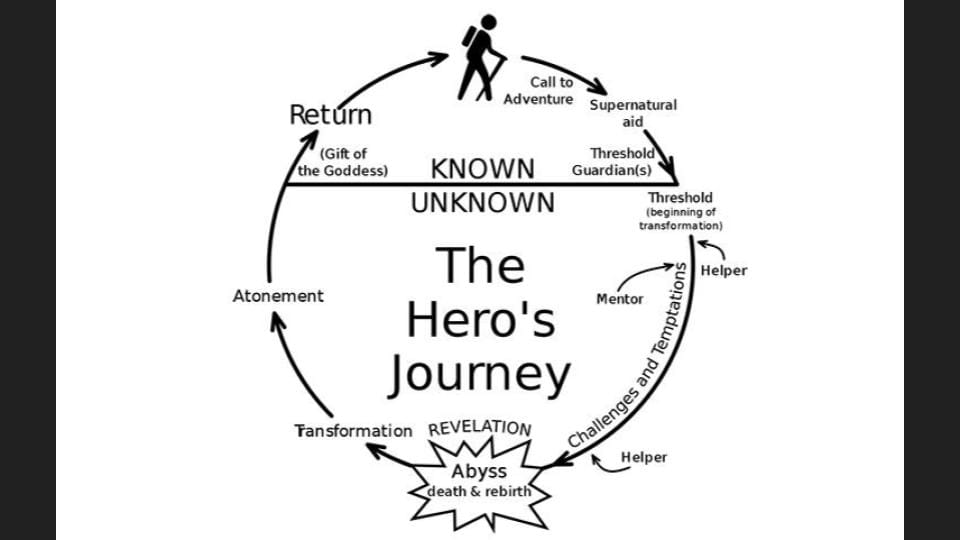

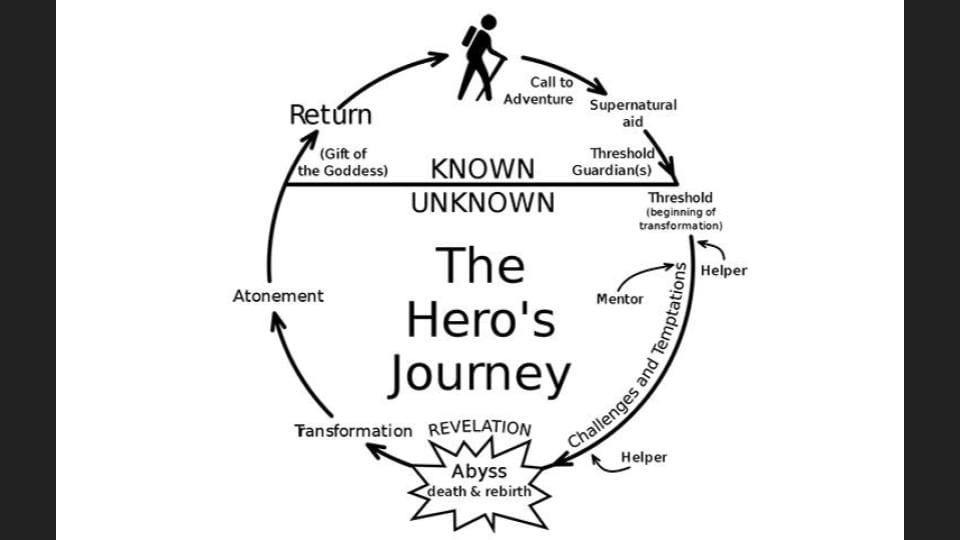

The Hero’s Journey.

Is this the student’s journey?

The academic journey you are at the start of?

Is the hero’s journey the student’s journey?

No.

Because we each have our own brand of heroism, right?

...

Weirdly, it is kind of my academic journey.

I finished my MA at Canterbury University in 1992.

I enrolled for a PhD in 2013, here, at AUT, and completed it in 2017, 25 years later. ...

In my first year doing the PhD, well-meaning staff would say, You’re at the start of your PhD journey. Which I hated.

But now when I reflect back on it, weirdly there are elements there that do conform to the hero’s journey.

(Why did I resent being told I was at the start of my journey? Because I could say my journey started ages before. And that it had led me to that moment when someone dared to tell me I was just starting out on it.

(At the moment when they did, well, of course I could not reflect on where I was: all I cared about was getting on with it.)

You’re probably thinking the same thing.

When is this lecture going to start?

(And this desire to get on with it had nothing to do with either getting on with it so that it was done, achieved, there you go, you’re a doctor. Like, you’re a wizard, Harry! And it had nothing to do with thinking, Oh, pack my knapsack, get out the door, I’m on my journey ... into the unknown.

(It had nothing to do with either any kind of journey or with any kind of end of journey, or, as others suggested to me, end of torment.

(PhD, they said, means Permanent Head Damage.

(The feeling of accomplishment in fact has never arrived.

(Is that so weird? No.)

...

I don’t want to be on a journey. Go fff... yourself, familiarise yourself, with your own journey! ...

So to each obstacle as it came... I thought I was totally prepared!

I mean, how hard can it be? Permanent Head Damage? What a joke!

I’d had worse experiences in a single day running a café than I could possibly confront on my 3-year ‘academic journey,’ my PhD journey.

Academics. What do they have to face? Do they clean the toilets at the end of the academic day?

Do they have to deal with the full-moon phenomenon, which did happen every full moon in the café, when every single person started acting really weird... That word again. Aggro from the prostitutes working up and down K’Rd. Yes, it was in K’Rd. Scratchy sniffy behaviour

from the regulars. And the staff... !

Oh, I’m really sick! I can’t come to work!

Is it another hangover?

Well, ... but I promise this will only happen once.

...

Yes, it can happen that academics have to deal with stuff like that. But it’s not part of their journey!

...

I’m sure you’re dying to know. How did my journey weirdly come to resemble this slide? ...

First, the call to adventure. Yeah, right, enrolling for the first year is totally like a call to adventure.

We’re leaving now! Take only what you need... Those books are going to get real heavy ... and you’re going to come to regret you brought your laptop... No! You haven’t got time to recharge your phone! And leave your charger... behind!

Totally like an adventure when your courses are conducted online.

Mine weren’t.

The call to adventure, wasn’t [one].

What was I thinking? Probably similarly to you, I didn’t know.

And I knew I didn’t hear any voiceover say the words, So the adventure begins...

I did think I knew exactly what I was doing. Over the 25 years from completing my MA to beginning my PhD I’d gained experience as a theatre practitioner. Because, yes, that’s what my PhD is in.

I’d had more than half a life-time working in the practice that was going to lead my academic research.

Again, was I going to let anyone tell me, Your journey is only just beginning? ... No.

Yes: all this equates, if you look at the image, to the part of the diagramme above the line, labelled ‘Known.’

I knew. I was a knower. I was not in quest of knowledge.

And again, I’d like to draw you in as well: are any of you, if you are honest, really in quest of knowledge? Really?

Knowledge. Isn’t knowledge that thing that if you have a really hard question, you search up the answer?

And haven’t you already in your lives had experiences that make you think, even if just a little, that your journey started way before you enrolled to be a student at AUT?

Although maybe there are among you those who are on a quest.

For knowledge. For certainty, perhaps, given the uncertainty of the times...

But I would doubt that you think at this point, the point of Let the adventure begin, that you think to yourself, The object of my quest will be found at AUT!

That’s not meant to be a downer: it’s great to recognise you are on a quest. And if for knowledge, then all the better.

So: the Known. Being a knower. Nothing to do with the guy that built the Ark. Ushered the animals on Two by Two. Floods and climate change and so on.

Being a knower has never been easier. Even without the prostheses of devices that answer questions.

...

A knower does not receive the call.

Even though the call may be given, they don’t receive it.

They don’t receive what is given.

And this goes for whatever aid or advice they may be given.

Even when it is highly relevant, this information is given still in the world that is known. So it belongs to what the knower already knows. Or the knower sees it that way.

Don’t tell me that!

That’s so obvious!

Where’d you read that?

In a Fortune Cookie? On the back of one of those self-help books for students starting their academic journey?

Give me a break!

...

Yes, my journey is taking its time getting going.

Supernatural aid. This we’ve touched on.

Yeah, there were in my case some angels. Some angelic assistance came through for me. In other words, I was in luck, and thankful to the stars.

...

I had a supervisor to promote my application to AUT for the PhD programme.

Events had also conspired, with the angels overseeing, to let me and my family change our living situation... hugely, wildly for the better...

And isn’t it a mistake to think of a journey as an actual journey?

Anyway, I’m grateful for that.

...

Noone tells you at that point, no matter how many angels are looking out for you, that you are about to cross a threshold.

The diagramme has it that it’s into the unknown.

That’s fair enough. However, I’d already crossed the threshold before I knew I was in the unknown.

...

My first supervisor was recovering from a brain tumour. She was not at AUT at the time. But she introduced me to someone who would end up being my primary supervisor. We had some meetings...

I was actually more bound up in the sad story of what was happening to my first supervisor, because when it happened it was a shock.

She was told that she couldn’t supervise because she was not employed at AUT.

So it seemed like the guy who ended up being my supervisor was... how to put this? ... for whatever reason I was now his student, his PhD candidate, not hers...

and he was, in the diagramme, the guardian of the threshold: he was guardian of access to the actual doing of the thing.

So, let the study, the research, the quest for whatever, begin!

Needless to say, I felt really bad for the person who’d supported me in the first place: where was she now? She sort of dropped from view.

I kept in touch for a while, as she went offshore to continue her career. Her career journey, which did continue.

...

We see in the diagramme, ‘mentor’ and ‘helper’ coming from different sides of the circle. Isn’t that what my new supervisor was supposed to be? Definitely a mentor.

The helper comes from outside the circle. And, I would say, that the mentor being inside the circle is also their being or belonging to the unknown.

The unknown I still hadn’t recognised as being unknown. Just as I hadn’t recognised the mentor for being one.

Unlike the angels I mentioned earlier, those who preside over the journey, at least those who presided over mine, which I have only on reflection weirdly come to see as being a journey, were not obviously helping.

My primary supervisor, for example, knew nothing about what I knew, about theatre practice.

OK, this is how he mentored: I had to take this first step, which looking back I can see was the step that took me over the threshold into the unknown, the step of ... it seems so obvious now ... I grandly called individuating my practice.

Better: individuating a practice into mine.

...

What I’d been doing for years was now the object of my research. And I knew all about it. I have no need to practice, I grandly said.

But a practice is distinct from this kind of knowledge. It is doing what one is doing. ...

That was it for the first six months. For six months I thought I knew what I was doing. It’s like ... walking. Try studying walking.

What? the whole field of walking?

Yes!

Now imagine someone saying, so, when you are walking, what are you doing?

...

That’s one side of the problem, the problem of individuation, that the next lecture will deal with in terms of modes.

You see, your practice is singular.

It is not, even before you specialise into one or another aspect of digital design, in one or another area of digital media, all that you know digital media to be.

It is not even all that you think you know digital media to be.

I’m not here to tell you, you only think you know, but let me tell you... No. Your practice is only what you do. Let’s remember this:

Pay attention to what you pay attention to.

For anyone trying to discern what to do with your life... That’s the ‘quest’ bit we talked about earlier.

Amy Krouse Rosenthal could have said, For anyone trying to work out what their quest is, or what journey they are on...

Pay attention to what you pay attention to.

All the info you need. Told you so.

Did you believe it? No.

Did I?

...

The other side of the problem, once you’ve realised that you may not need to practice, after all, you might be an amazing and proficient animator already, but you need to have a practice, meaning, you have to know what you are doing that is yours, and singular, and, although it participate in the whole field of digital media, is set off from that field... Initially by your attention... The other side of the problem is owning it.

We have talked about this owning thing in relation to choice.

I said, Bergson commends himself to our attention over Freud... well, not in those words. I said, I like Bergson because he’s all about not reducing the nature of inner experience and does not tell us that what we feel is not real, whereas psychoanalysis tends that way... I said you can choose the theory you like. But with a caveat, a warning, understand that by choosing you are affirming. You are actively choosing for.

...

You might think that when you come to choose a specialisation in digital media, it’s about what it makes you happy to do, what you already know how to do, what maximises your utility, what maximises the utility of your time at AUT, what maximises the utility of your investment at AUT, what will give you the most pleasure or the most money, or, hopefully, a nice compromise between the two, and amongst all of the options... However, you are also choosing for what it is you do.

...

Does a banker ever think about it like that? A financial advisor? A stockbroker? A corporate raider or an economist? Probably not. But I know plenty of doctors and nurses and care workers who do. Except they tend to endorse the whole field. Until maybe a crisis comes.

For a doctor, a medical doctor, it can come when the medicine they practice shows itself to be inadequate. In some way. It needn’t be as profound as losing a patient. It can be when the field in which they practice shows itself to be more interested in the economics of medicine than in the care-giving or healing power of medicine...

Now, a medical doctor can cynically continue. And usually, given the length of the training, and what they’ve invested into it, does. This is what we mean when we say they’re invested.

For the religious, this is usually called a crisis of faith. Many practitioners of religion long since ceased to believe... and simply go through the ritual...

You get the picture.

So you choose your specialisation knowing you might be called to account for it.

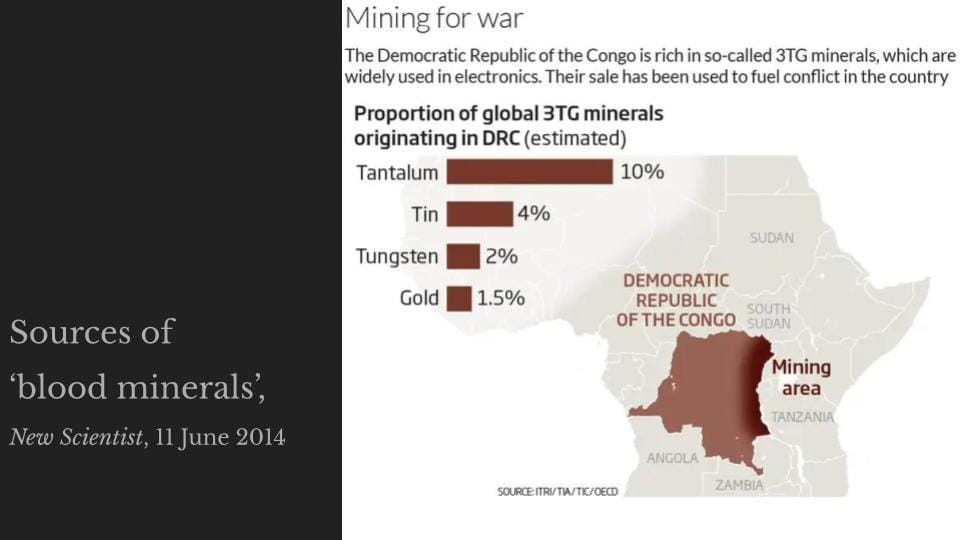

Do games designers ever wonder about where microchips come from? About the economics, politics and methods of extraction of so-called ‘blood minerals’ inside every cellphone?

Yes, you can say, We are phone users, not phone practitioners.

Same as any practitioner in digital media, they simply use the tools.

And what is the difference? The tools make no difference.

Until you ask yourself what is my practice and what other practices does my practice support? What is my practice and what other practices does the practice support that I call mine?

We have the individuation of practice into what I do and the individuation of practice into what I choose.

We are less likely to call our own leg a tool, an instrument for walking, than a possession like a car.

You see, a practice is easily taken for granted. Until it is yours and you have to call it yours. And you call on yourself to call it yours.

Until you have to. And the choice suddenly appears to be very real.

What is it for which I reserve the word, mine?

Choosing a practice is different from a calling or a leg or choosing to drive a car. I’m not trying to make it more difficult. I’m trying to point out the importance that this little word has, my, in my practice.

Step one. And this is how my mentor mentored me.

What you are happy to call yours is not yours. Is not happy to be called yours. Is either set off from the field or is from you, like an unhappy leg. And once set off from the field by your attention needs to be something you are willing to take responsibility for.

It is as unlike a brand, and is as unlike a personal brand, as a leg.

I mean to say, the choice is not like this because this time it’s personal. No. Whoever called a leg personal?

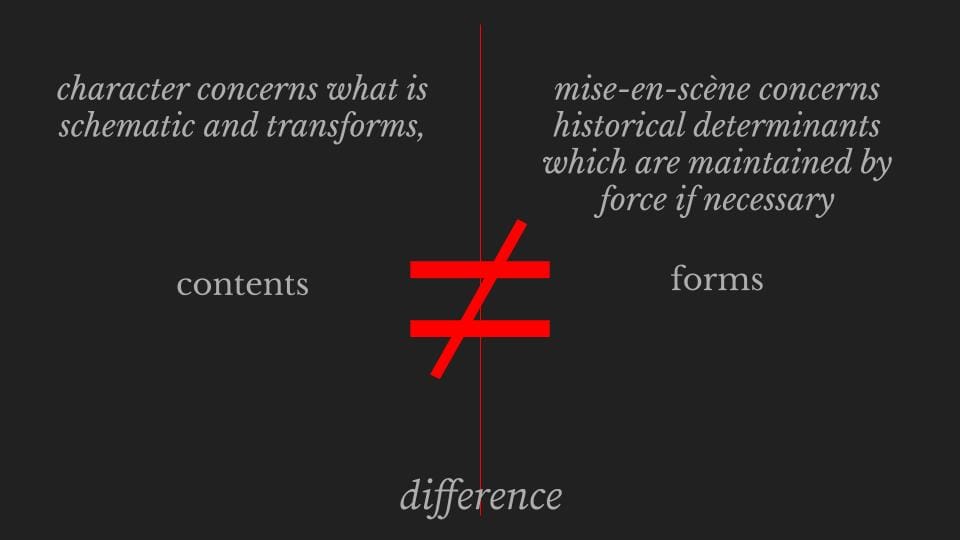

The problematisation of the field. This is what it’s called. And we can think of it terms of mise en-scène: the field of digital media, or a specialisation in VFX or other specialisation, being the mise-en-scène; and then the character... well, a gap has to open for the character to come through; a question has to be asked: there’s a problem or a contrast between the one sort of time, the linear time of the familiar narrative, in which technological progress advances the field, the specialisation, especially, of VFX, and the time of the one whose practice is in VFX, who... does what?

What else? They reflect on the field; they stop the constant doing and attend to what it is they are doing. And through this hesitation comes a character who doesn’t know what’s going to happen next. The name this character has is my practice.

You see how it works? The character individuates through the contrast and difference they experience between the endless narrative advance of the entire field, the mise-en-scène at any point, and the attention perhaps to certain details that make up the way they operate the practice, that make up the way you operate your practice.

Why details? Because all it takes is a schematic.

A link between the problem field and the operator... And we have individuation. Like, we have Lift Off.

This my mentor provided me with from inside the circle of the unknown. The unknown known, as Donald Rumsfeld says so would-be poetically:

would-be because this is the United States Secretary of Defense on February 12, 2002, justifying the invasion of Iraq on the basis of strategic unknowability, justifying war and loss of life, and the more or less illegal invasion of one sovereign state by another, on the basis of saying that it is unknown whether Saddam Hussein has Weapons of Mass Destruction (he was accused of supplying terrorist groups with Weapons of Mass Destruction) but doing about it what would be done if it were known.

Proceeding into the unknown as if it were the known.

As I did, with much less disastrous consequences, or disaster on a limited range, on the individual scale... (This private disaster we can see at the bottom of the diagramme.

(Where it is encouragingly called the Abyss.)

Whereas the helper came from outside the circle. He was on an advisory panel brought in to decide whether I should be allowed to proceed with journey. That is, my PhD candidacy.

...

The problem with the political field now and at the time of the 2003 invasion of Iraq is less of knowability or unknowability, or what Rumsfeld also at the time referred to as visibility, saying, “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are,” but that of there being no outside to the circle.

No one to cry Help to, as Rumsfeld did, saying, “Help! I have no visibility into who the bad guys are.”

None of the promised rejoicing happened when the statue of Saddam Hussein was toppled in the street, when the people of Iraq were liberated from Saddam Hussein... And none will happen for Putin if things get that far...

Iraq wasn’t grateful for the war, asked why not? Rumsfeld answered, “Stuff happens.”

The helper from outside the circle... came in on a video link at the six-month mark, marking half a year of a journey I refused to believe I was on.

I had prepared a major theoretical justification for what I had been doing, and he introduced himself as always being skeptical about research being led by practice. Just as for this course we ought to be. We ought to be skeptical about the place of theory.

I mean, making better software for handling VFX, creating better techniques in animation, research improving the tools and technology for digital media is one thing. But thinking through making a digital moving image sequence ... is another.

Imagining digital media practice to be good not to conduct research on but to conduct research with is ... is and has been the theme of these lectures. Not to justify the role of theory in digital media but to help us in our practice, in our individual practices. It’s not that I see no better use for theory than this, I see theory as being of no other good than this.

And help is neither what the helper on the advisory panel intended nor is help what I got from it.

Or, let me put it this way, the help was as helpful as being turned upside down. It could only be called helpful if we are considering the journey.

...

For the character of the practice, the walker walking their walk, the one who in this diagramme is called a helper can be ... I mean, look at how the arrow leads down, down and down, to the Abyss.

If I hated the idea of a journey and resented and rejected it, to the idea that the helper was one, I’d have said, No. This person is a bully. This person is inimical to me. This person is full of macho bullshit.

What did the helper brought in for the advisory panel do that was so bad? To every theoretical point I raised, he said, But what do you do?

...

A Mexican standoff is usually depicted as a threeway, if one shoots one, then the other shoots them, and ... jeopardy.

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966

(Worth playing in its entirety as much for the eyelines as for Ennio Morricone’s amazing score. 1966. Directed by Sergio Leone. Clint Eastwood is the Good. Lee van Cleef is the Bad. Eli Wallach is the Ugly. In the greatest Spaghetti Western ever made.

(Why Spaghetti? Because made in Italy, from the mid-1960s and shaking up or twisting the whole machismo bullshit, amongst other things, of the traditional American Western.)

Who was I in the three-way standoff? ... if it’s heroism I’m after then I’m going to the abyss... No. There was no heroism. And no temptation of gold, as in the movie. Neither was there any temptation to view what was in reality humiliating as hiding within it gold; nor was there any temptation to view it as a challenge to be faced. Just the face-off.

The helper asked, what do you do?

What do you mean, do?

I mean, when you are doing your practice, which I presume you actually do, what are you actually doing?

I’m making... I’m directing... I’m... It was as clear to me as if he had asked, You walk, right? Yes.

What is it you do when you’re walking?

Well, I think.

Do you?

Yes.

Then your practice is not walking but thinking.

...

If only I’d answered, my walking is a kind of thinking.

...

OK. So now I am defeated by events.

My theory bag has been emptied on the floor... and that’s all I left home with... just some ideas. Some borrowed ideas. That I was applying to the practice.

Like labels. Labels with different cool sounding names on them, authors of books, names I thought would sound impressive in an academic setting, because they were names of the authors of books.

This is when, to use a currently popular word, you pivot, right?

As the Mexican standoff scene shows, I didn’t budge. I was in fact frozen.

Breathing. This is another word you could use instead of walking. But what is it you do when you are breathing?

Living, are you?

So your practice isn’t breathing, it’s living.

Or getting dressed in the morning.

What are you doing when you get dressed in the morning?

I’m following the convention that this is what you do. You get dressed in the morning. So your practice is really just to do with following the convention? Why didn’t you say so. At least with following the convention we can start to retrace our steps. ...

Now, following the convention is, we said before, like saying my practice is in digital media, or in some specialisation, animation, VFX, motion capture, post-production, 3-D graphics, and so on.

That’s fine. But what do you do?

I just follow the convention that applies to my field.

Great, now we can start to retrace our steps, because to call it that, a convention, is to undo its hold on you a little.

It’s just a convention of your field. No more than that.

And not only that, to see it as being neither more nor less than a convention is to start to undo it. It is for the character to reflect... And to fall out of the abyss.

That’s all of the exciting bit.

Did I ever get back home?

I never left.

Why have I waited until now to talk about narrative?

Because of the automatisms of narrative.

...

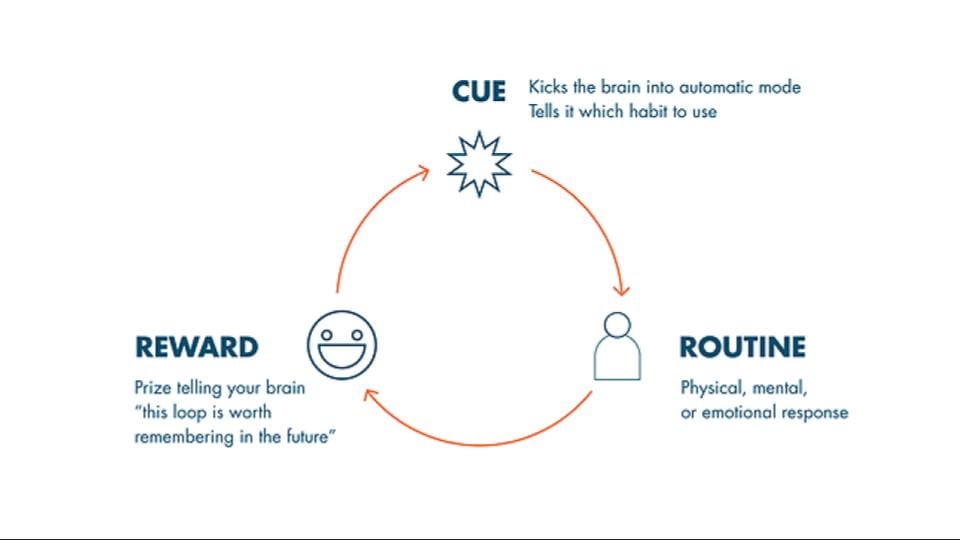

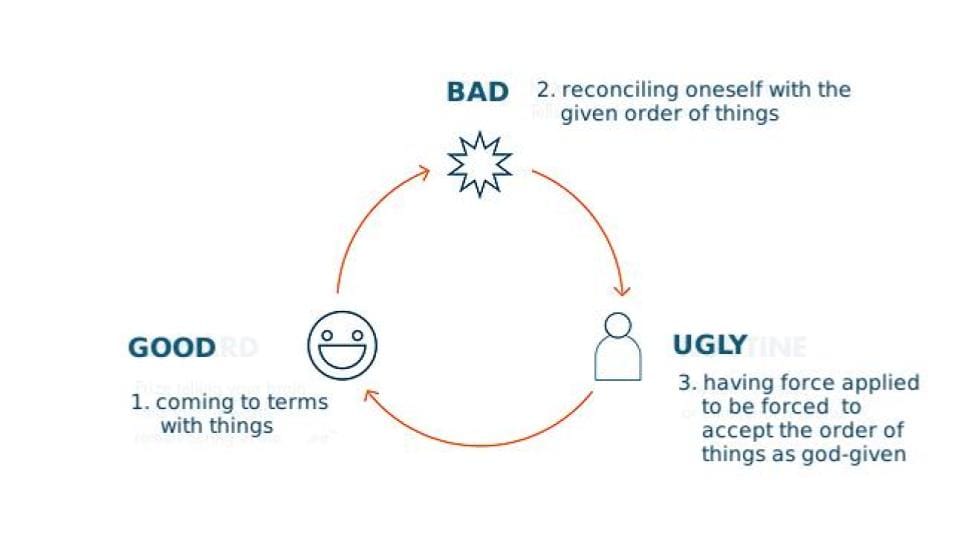

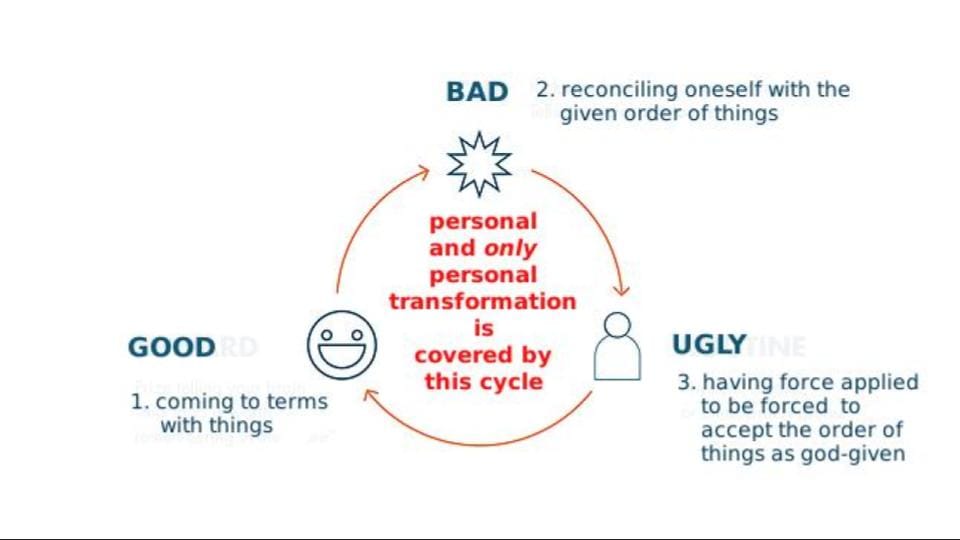

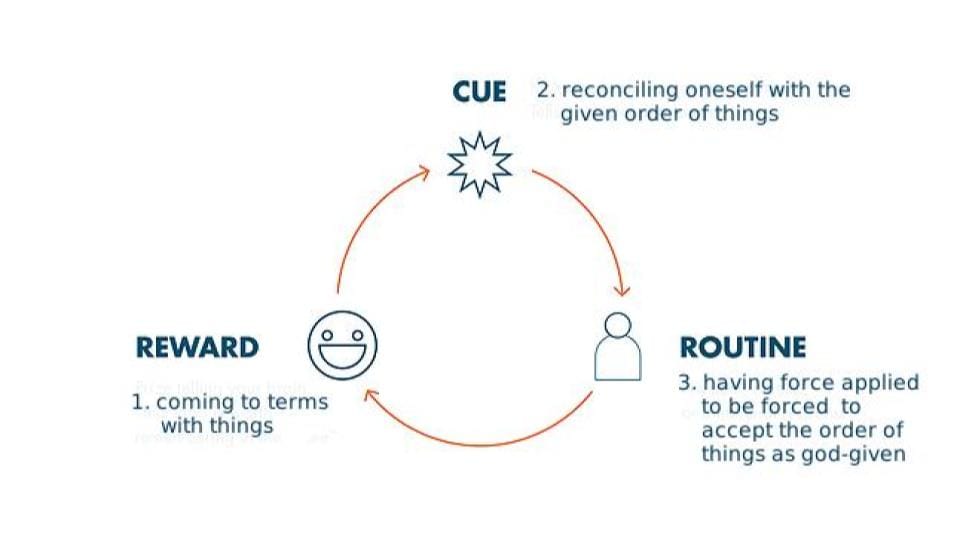

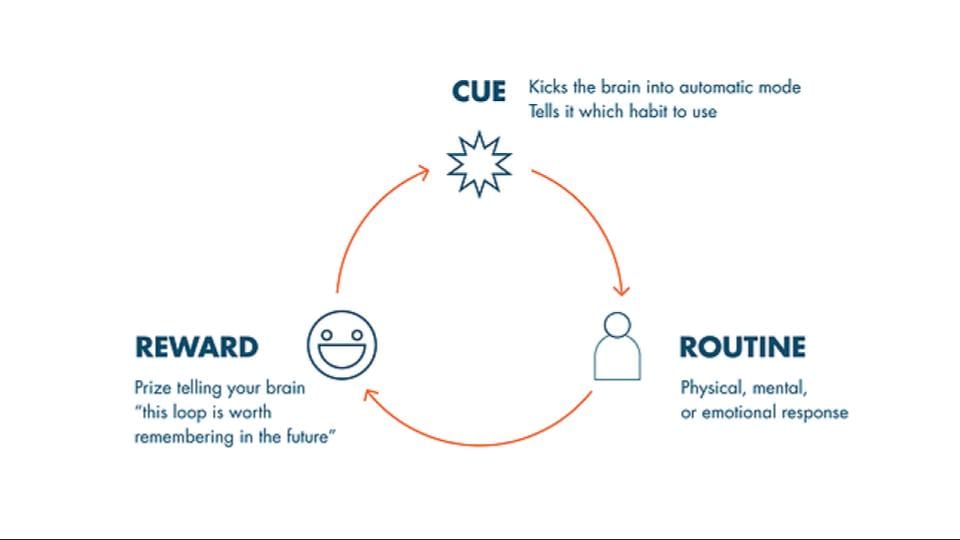

When we tell stories about ourselves they are usually about coming to terms with things. In the story... it’s not even a story arc but a circle, like a habit cycle...

...but let’s say it’s an arc: in the story arc of the Hero’s Journey, sometimes known as the Quest, we see this reconciliation...

Note the clockwise orientation of both these slides.

We can see this reconciliation in atonement... Oh, yes. It comes after transformation. And transformation comes out of or from the Abyss. Because in the Abyss, Revelation.

What is the Hero atoning for? It’s a religious term these days: in the Christian tradition, the sinner atones for their sins.

The sin the Hero has committed is...

Is it the fact they headed straight for the Abyss? Not without some help. Not without some mentorship...

Or is it to atone for the arrogance of claiming to have had a revelation?

That’s a great sin: think of the hero of tragedy who claims to have it all figured out... And no sooner said, than the gods punish.

This is a detail from Masaccio’s The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, ca. 1427. The punishment is for the sin of eating of the tree of knowledge.

...

In the Western classical tradition and in some cases in the East, punishment takes the place of atonement. Because the tragic hero does not recognise their hubris.

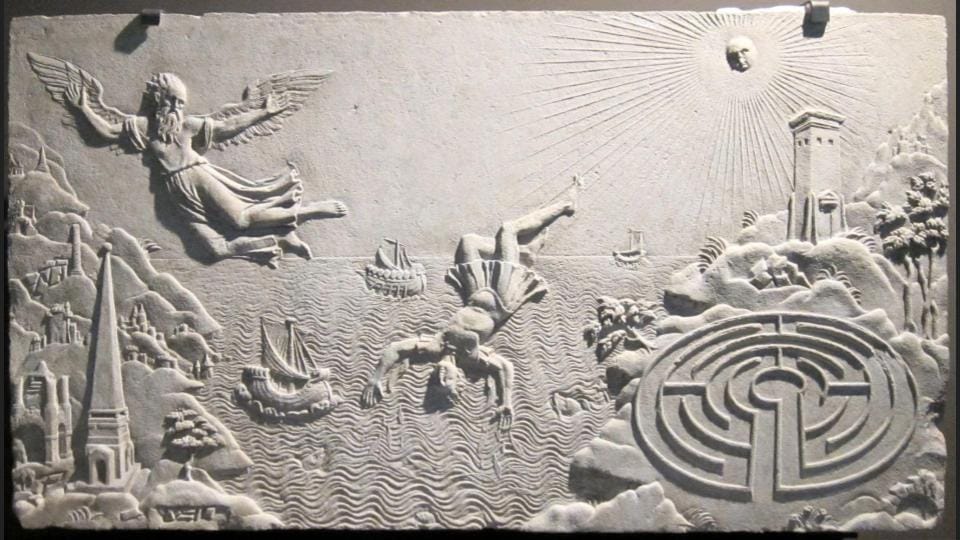

Prometheus, on left, God, on right. Dejan Jovanovic, a contemporary art director, has God showing Prometheus the dangers of technology.

...

Hubris is pride. Which is seen by the gods as a challenge, that the gods meet by putting down the one who challenges their place in the order of things.

(If only Neo in the matrix was a tragic hero.)

Punishment. Atonement. Reconciliation. Whatever.

The Hero has to accept their place in the order of things. And the force to do so... comes from inside, atonement, or outside, punishment. Or, the one we’re more familiar with ...

Yeah, that’s Jack Nicholson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975, directed by Miloš Forman. ...

Well, unless the revelation is backed up by established authority, the established authority of science, and so on, to have a revelation is, if you don’t keep it to yourself, a medical condition.

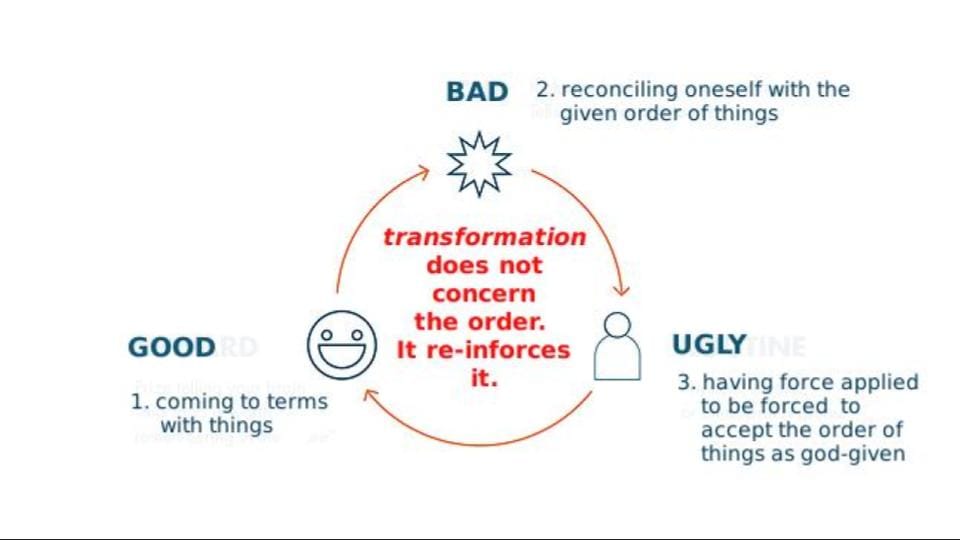

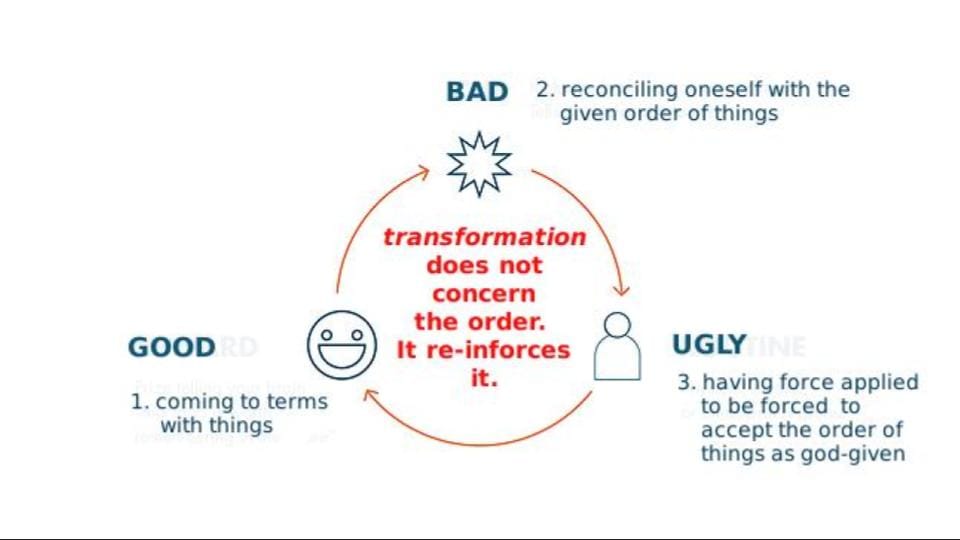

Transformation: who is transformed? What is transformed?

It’s not the order of things. Even after their transformation, the Hero has to accept their place in the order of things.

(This might recall for you some things I said about Kant.)

So we may as well say it: truth according to the existing authorities, good; revelation as to another possible order of things, bad; and personal transformation, until it’s atoned for, simply ugly.

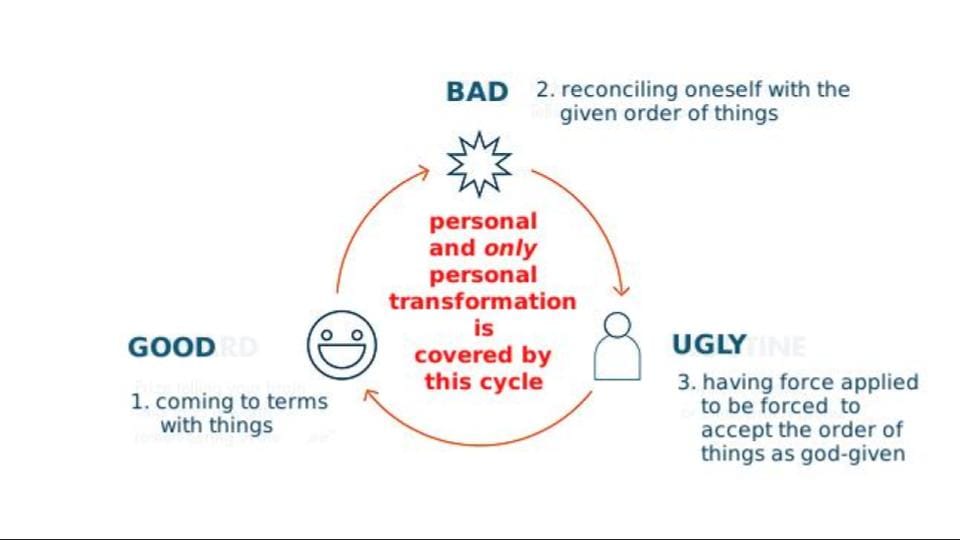

These are our three automatisms:

(the automatisms of narrative: 1. coming to terms with things—good; 2. reconciling oneself with the given order of things—bad; 3. having force applied to accept the order of things as god-given—ugly [and the other part of this: transformation does not concern the order but reinforces it. Personal transformation is covered over by 1. then 2. and 3.])

Yes. Our Mexican standoff. Except we know beforehand who wins.

Having atoned, the Hero is reconciled with the existing order, backed up by the authorities...

The Hero leaves the sphere of the unknown and returns to the known. It’s not a new known. True, they’ve changed. But...

...so what’s the gift of the goddess?

Some kind of memento perhaps. A reminder of their journey. Or could it be the power of story?

This after all is the only treasure they’re allowed to keep.

(I’m thinking of Bilbo Baggins.)

There and back again, is another way of saying it.

...

The story goes inevitably like this: I faced some challenges, but I had some help, and mentorship, I didn’t know.

Then, I did. I fell out of the Abyss. I paid the price for knowing. Learnt to keep it to myself. And felt very different afterwards. And now it’s time to tell my story. Thank the goddess I can!

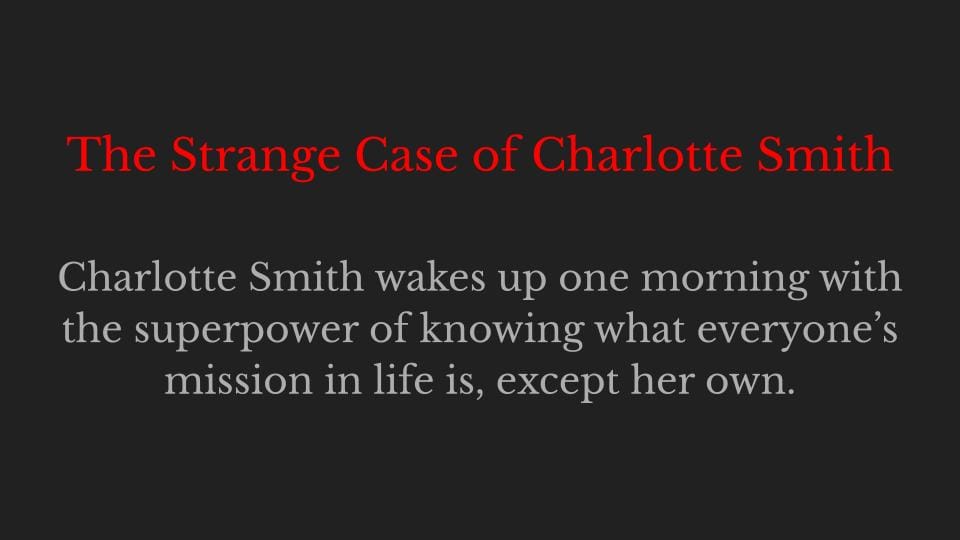

(It’s not so different from the story of Charlotte Smith. And that’s the point.) ...

We know this story from just about every story we ever read... even thanking the goddess... or god... or some extramundane power... the SuperAuthority. No one thanks the police. Or the government...

And that’d be nice, if for once the family that faced challenges together, who went to hell and back, rather than thanking them for the return of their little baby girl, thanked the police for the gift of being able to tell their story.

No, they thank the help for helping. And the extramundane super-authority for having them survive, so that their story could get told.

I survived to tell the tale means, not that I lived, but that now you have the benefit of reading or hearing of my journey. It ends with something like, You and I, we’re alike. I’m no hero. We each have our own particular brand of heroism. And so on.

The story is of coming to terms in the end with the way things actually are, which is how they were, only I didn’t see it at the time. You see me changed.

This is the story of facing any personal challenge, which seems to be the only place the narrative can be changed.

And this coming to terms with things that the story-arc imposes... whatever the shape it imposes, off-the-scale happiness, or living to tell the story... works at the institutional level as well.

1. It keeps tales of personal transformation personal.

2. It makes sure the revelation of personal transformation in public is... not punished, not exactly atoned for, but, the one we are more familiar with, institutionalised. Given treatment, the one, who believes to them has been revealed the big truth, is brought back into line.

The atonement comes afterward and can be public.

3. And this time around, the atonement is more like an apology. It states my personal responsibility for what happened. What I saw clearly in the end was that I was at fault, not the institution. The fact that I saw my mentor as obstructive, or my helper as full of macho bullshit, at the time, does not serve my story, which should be unambiguous. It should state that the institution is not at fault. And this is supposed to have the force of a revelation.

And, finally, this is the gift of the goddess, this coming to terms with things as they are through the power of story. It’s habit-forming.

So that, now, institutions also have stories. And it’s how they maintain their, what we called in the last lecture, their structural integrity. What do they do?

They stick to the narratives they have made up to show them in a good light.

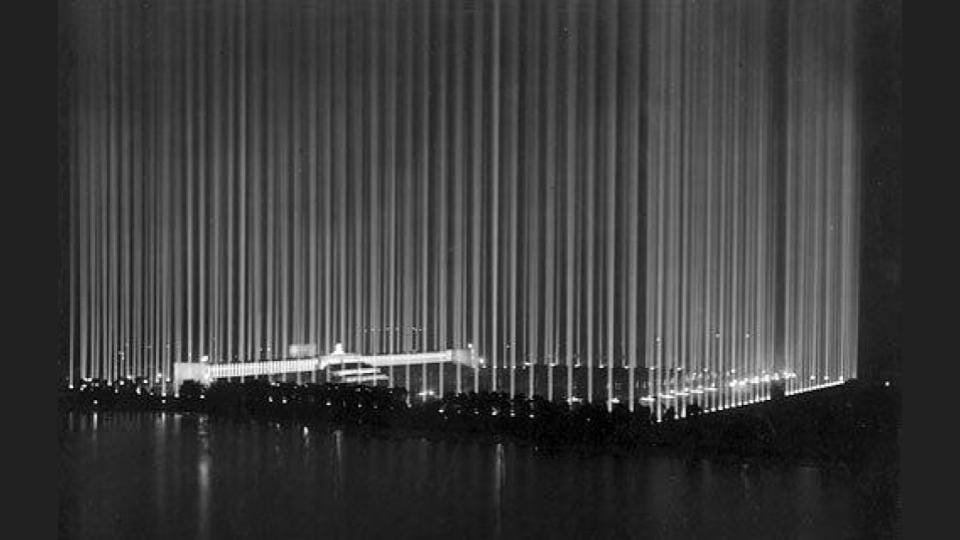

The moving image has a role to play in this too, as the slide shows: Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the Cathedral of Light in Triumph of the Will, 1935.

...

The institutions that are nations are like this.

Germany sinned greatly between 1939 and 1945, and to Germany was revealed its sin, and everyday Germans on the street said we didn’t know.

We thought they were burning rubbish ... in the camps.

But it had to feel like the revelation came from the inside, not being told by other nations that Nazi Germany was immoral. And then the public confession of a personal wrong, despite the fact it was a national wrong.

And then, transformation. In fact, in Germany, called the ‘economic miracle’ of recovery, after the war. Germany is now maintained by its story of coming to terms with what it has done. That is, the institution of the German nation is.

And we can say the same thing of our identity, as an institution that is supposed to be stronger now for having in the past done wrong, but realised the wrong, so goes the story, and now at least, trying to do right.

The same thing as a bank that was bailed out after the 2008 financial crisis and has learnt from its mistakes. So it says. And so maintains, through the act of story-telling, the gift of the goddess, the status quo.

And so prevails the status quo.

Yet we say, for there to be change, we must change the narrative.

The narrative has the facility of automatic self-correction. The narrative function is that of a thermostat. It is a form and it maintains the form.

And as a form it has to look and sound and taste and feel and, yes, smell, like it is coming from the inside. The revelation is its in-form-ation. It has to appear as if it comes from that other sense we mentioned, apperception.

As a form, it has to look like it is coming from the inside no matter the contents. No matter how smelly and unpleasant they are.

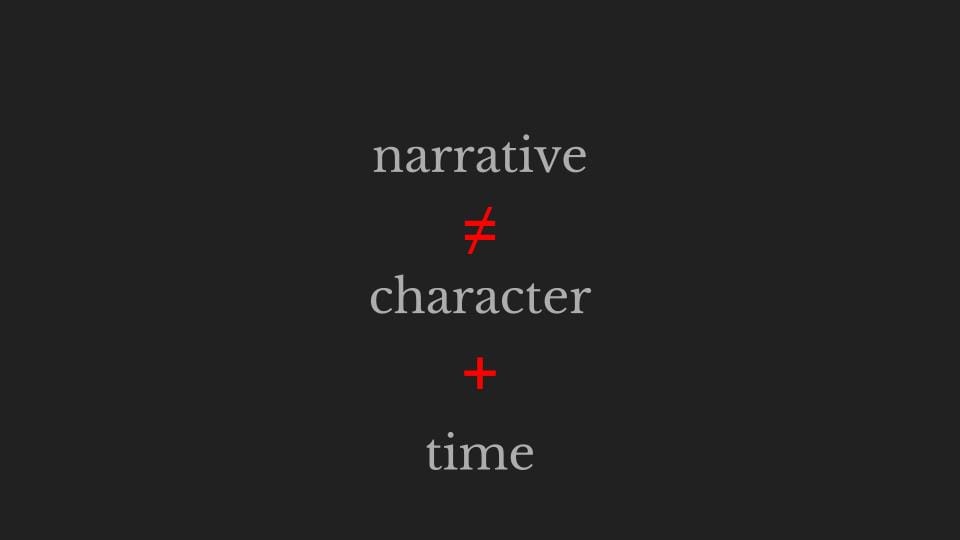

Narrative is institutionalised habit.

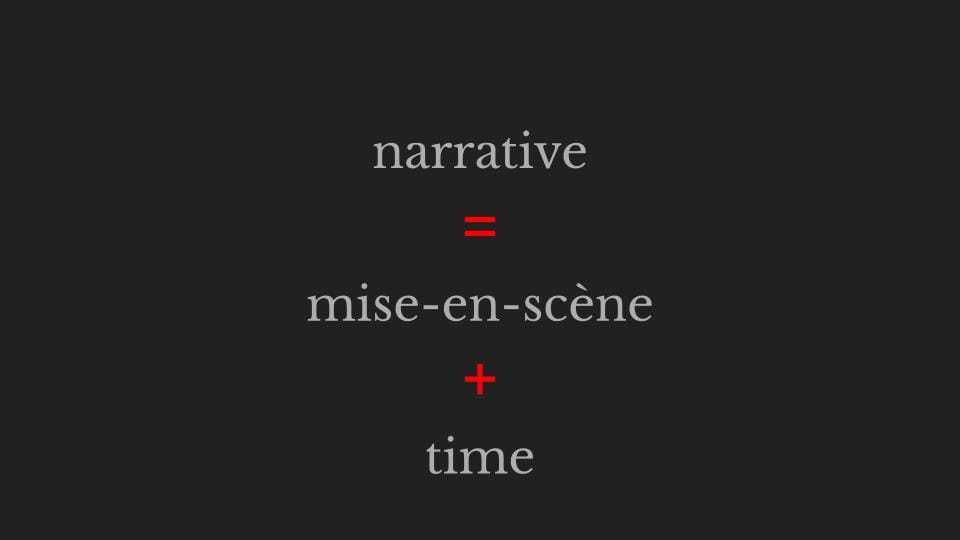

As institutionalised habit it conforms to the mise-en-scène.

It is how institutions maintain their mise-en-scène.

Conforming to the mise-en-scène means the mise-en-scène wins.

The mise-en-scène of the institution. The mise-en-scène that an institution is. So that narrative is naturalised.

...

This is the story: the habit of narrative, of story-telling, is institionalised as the natural form. And the mise-en-scène that the institution is is the confirmation of that. What do I mean by this?

I am talking about the historical determinants. Remember we identified the mise-en-scène as being about giving the historical determinants of the moving image sequence. Having the right lamps for the period. Finding the right locations. Assuming the appropriate social setting. From which the character differed.

Now narrative comes along and makes it the most natural thing in the world, the mise-en scène, despite the fact that we know it, mise-en-scène to be a construct. It’s not a given. Not an eternal truth. But changes over time. Is subject to our first concept: historicity.

What narrative does is add time.

But what sort of time? Well, the time exactly of ‘it is what it is.’

Clocktime.

From which, we remember, we said the character differed. We even said that this is the minimal condition for character. The condition of animation.

The life of a character is only in its linking to its inner duration.

This inner duration a character experiences as outside. The world the character sees and has to face that we don’t.

The character of me, who, on reflection, sees their academic journey weirdly mirror the hero’s...

...except for the minor detail of not being a hero.

But we have to ask, did I change the narrative? No. I was exactly brought into the institution. I became part of the furniture.

At least that part of me did. And what if I wanted to change the institution?

I would have to make recourse to another timeline. A timeline that is not that of the story I told you in the first half of this lecture.

There would be a hesitation. A gap between what I did and what the institution could accommodate.

Would I have to fail? That’s one option. It happened to a friend and he took it for a victory.

So his story went like this: more in the classical tradition, where for the sin of pride, of having perhaps a revelation of truth, he did not atone, but was punished. Did not receive the gift of the goddess. Did not live to tell the tale.

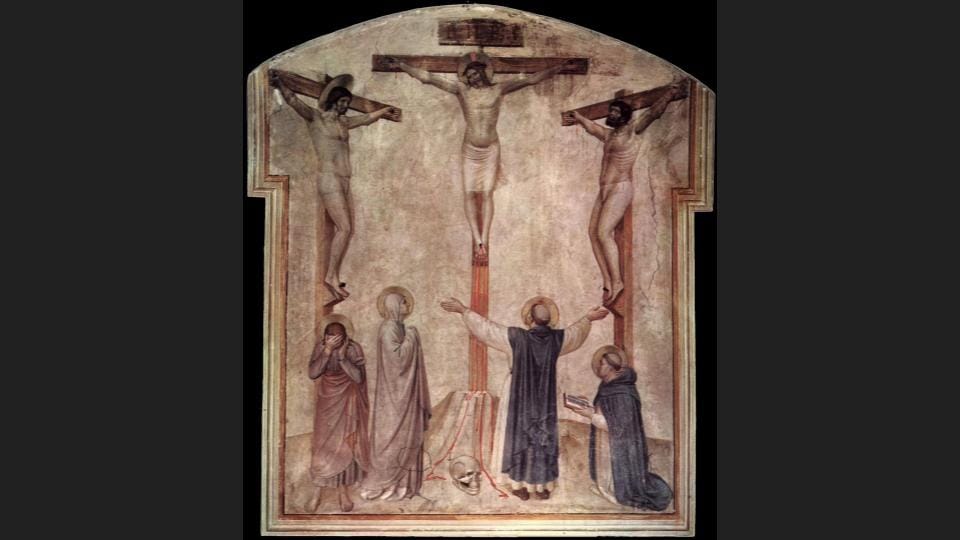

And the other way we can think about this is that his punishment went all the way to sacrifice. For him, self-sacrifice, sacrifice of your career for what you believe. And this happens too. Martyrdom and crucifixion.

What the other option is we will be exploring in the next lecture.

...

The essence of character is in the relation to memory.

Memory is the other sort of time we give characters recourse to and the reason we make recourse to characters. Even the characters of ourselves.

Now story comes along with its institutional mise-en-scène and tells us what is currently held to be the truth about story and narrative, that human beings are story-telling by nature.

Being that it is in our current era that story is so portrayed, science has a hand in this: it is maintained that narrative is how we humans make sense of the world.

What I am saying is that this world is limited to habit by the automatisms of narrative.

We have seen this before, the seemingly automatic machine-like responses of habit. The motoric.

We have seen also the opening onto memory. And if we could make story itself a character here, we might ask it to look into its own perhaps 2.6 million year old history, to find in its memory banks an adequate image for the world we live in today.

This is exactly what genres do. They go back to historical models. And it is therefore said that the number of plots are limited, to six, by some reckonings, to seven, by others, to as few as three, by others.

Story finds in its own memory other stories and fits them to the basic facts of our today existence. A romcom will take a plot from Shakespeare.

An action drama might go back to Homer and Odyssey of Odysseus.

A psychoanalytical story is sure to mention Oedipus.

But what if story cannot find in its super-capacious memory banks anything to fit the situation it’s faced with right now, today, in the world, but also in your experience?

What if story looks in the mirror and... cracks up?

What if narrative goes into the unknown?

The unknown unknown it doesn’t know.

That is the third loop of memory, isn’t it? The one that breaks the habit. The one forced by the events that happen to her, him, them, to start thinking, to start creating.

I can’t mention the crucifixion without quoting this,

by Samuel Beckett;

yes, the same guy who in Worstward, Ho! said, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

And Beckett,

who wrote at the end of the well-named The Unnameable, ... “where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

You recall that on the hill of Golgotha where Christ was crucified two thieves were also crucified, one on either side of him. This is what Beckett said about them:

“Do not despair; one of the thieves was saved. Do not presume; one of the thieves was damned.”

This seems the best advice, for any character, on any journey.