moving image: theory | context: lecture 6

I want to do two things here.

I want to ask what drives narrative?

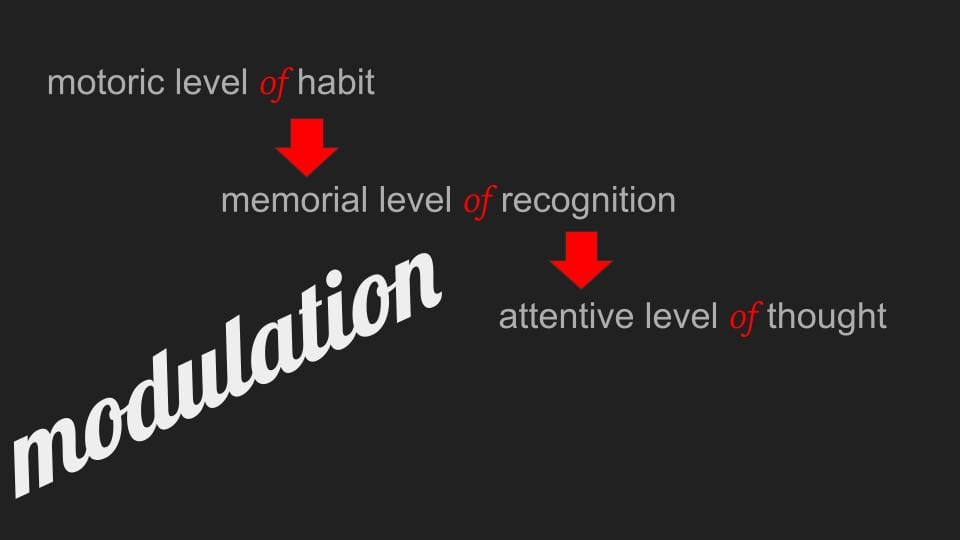

And I want to bring in this idea of modulation.

What is it? And what is it that it is our topic today?

I have some idea. I have some idea that the two questions are linked and that modulation provides us with the means to link:

what drives narrative?

and the concept of modulation,

because modulation involves the unequal.

What drives narrative? Our desire to see things done, to hear of brave and heroic exploits, and silly entertaining ones:

And tragic ones, like that last one, too...

Desire seems to drive narrative. But by wanting to see and hear about what happens to others what are we desiring?

If story-telling is really how we make sense of the world, of the world and ourselves, I might add, is our desire to make sense?

Nonsense.

Story seems to be a form of experience... but we don't desire the form. Is it the contents then that we eat up? so that we can't get enough of it? of ... cat videos.

(I was tempted to play it again...)

In other words, the desire to be told stories... seems to be tied in with what has been called 'vicarious' experience. Vicarious, meaning the experience of another.

Other terms come to mind, 'second-hand' experience, and 'indirect' experience. But we have been asking whether the experience is indirect.

Isn't watching a moving image sequence a matter of direct experience?

Audiences watched the Lumière Brothers Le Repas de Bébé. It was on the bill, in the programme, for their first ever screening in front of a paying audience in 1895.

What do we experience watching the film? Perhaps some curiosity. So I'll give a little more context. It can't hurt.

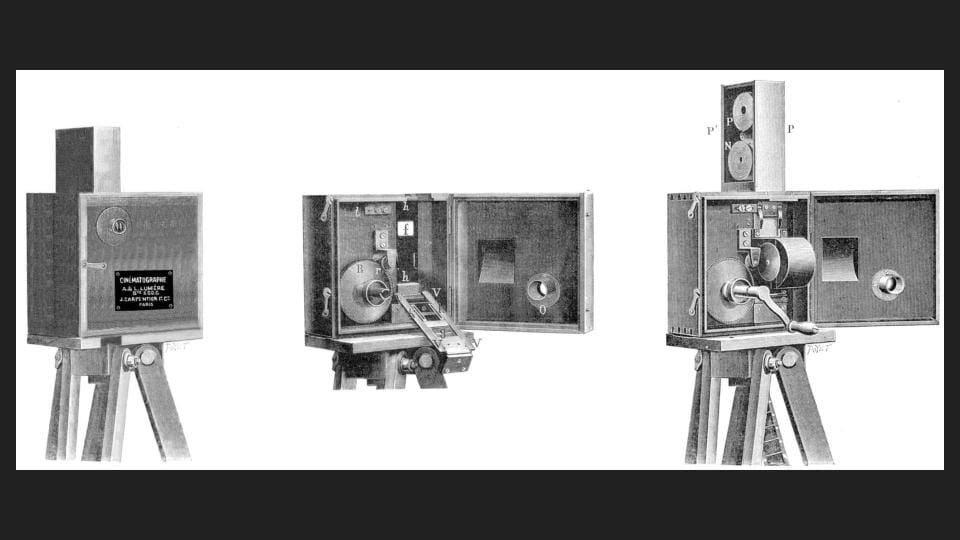

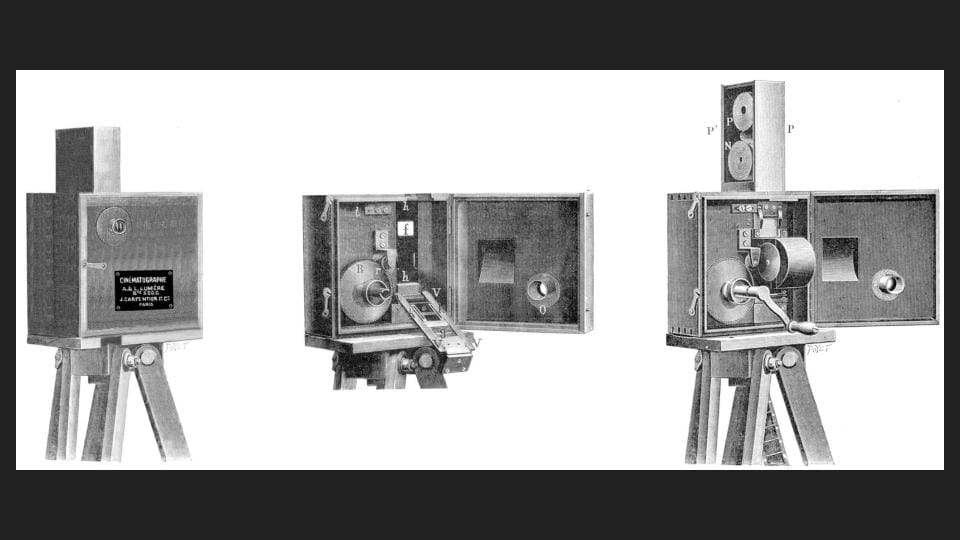

Shot at 16 frames per second on a 35mm Cinematograph, the Cinématographe of the aptly named Lumière brothers, aptly named because the surname means light. This cinematograph was capable not only of registering the image on celluloid but, also, of printing it and projecting it.

The Lumières' innovation was to have retractable sprockets advance the film, the film had the signature sprocket holes down the sides, retract, to leave the individual frame stationary for exposure, and, once exposed, to advance the film to the next frame, at 16 frames per second. It was handcranked, later mechanised, and reasonably light and portable.

The name cinematograph means, from Greek, motion, kinema, and graf, writing. Motion writing.

This might recall for us Bergson, his feelings about the kind of motion which is not real for being a compound of instants which are not real. And are definitely not the measurement of time.

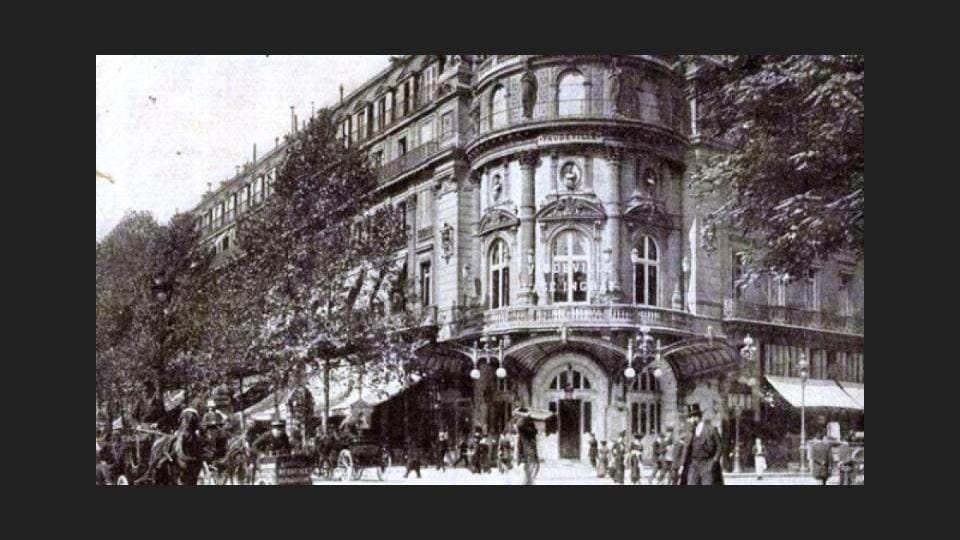

The first screening of Le Repas de Bébé in front of a paying audience was at Salon Indien, Grand Café, 14 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, on 28 December 1895. So it qualifies as the first commercial cinema event.

The film features Auguste Lumière, his wife, Marguerite Lumière, and the baby, Andrée Lumière, she was one at the time, all appearing as themselves.

The film was shot, directed, and produced by Auguste's brother Louis Lumière.

What do we see? A baby of one who is clearly on solids is being fed outside. By her father, while her mother pours and drinks coffee.

Going from the terms actualizing the structure, what can we say about that structure? That is, let's do a bit of formal analysis here.

We have no problems saying that the camera follows the action of the characters, the character vectors. There are no edits, no cuts or montage, except at the beginning and end. What sort of shot is it? One that captures the whole scene.

The camera does not move. It is locked off; from the context of knowing what a cinematograph looks like, we can say it is on a tripod. Yet there is movement of the frame. And from the context of knowing the mechanism, we can say that it's likely this is not a deliberate effect and not intended to contribute to the scene. Not an artistic effect but an effect of the technical apparatus.

Or should we think of it as being an artistic effect since it has an affect on us? In that sense it does contribute something to the scene: it expresses something tied very closely to the scene, its temporality. Its time in technical terms. In the technical terms which actualise it.

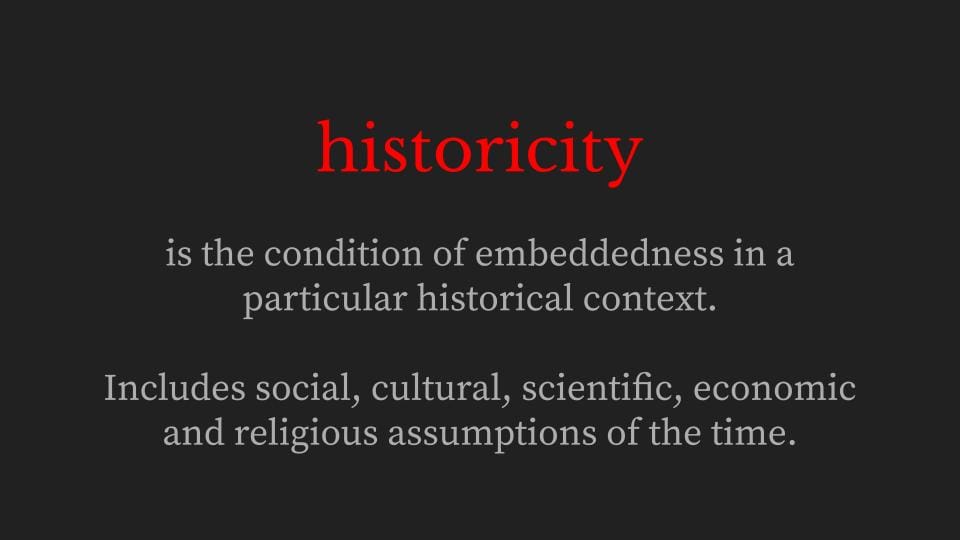

So this too belongs to the structure, to formal analysis, by adding to the sense of historicity, the embedding of the scene historically, economically and technically, in terms of the technology.

What causes the juddering of the frame? From the context of the technology, that is, the technical discourse (techne—from Greek gives us the familiar word technique; logos—also from Greek is a broader category than the word we are familiar with, logic. It's closer to discourse), from the context of the technical discourse, we can guess at the cause, but would need further concrete evidence to state it as fact, that the sprocket system is not so accurate as to line up consecutive frames on the celluloid. The frames are just a little out each time, 16 times per second, the shutter opens exposing the film. They are not brought into the perfect alignment that allows the progress frame-to-frame to become invisible. This progress is visible and has a visible effect.

We also know the motor component to be the hand of Louis Lumière. Would this further explain the movement of the frame, in contrast to the movement in it?

I don't think this clip has been corrected, as some early films have been, removing the jerkiness produced by differences in the frame-rate in playback. The action looks neither to speed up nor to slow down: it is this that would tell us about any inconsistency in the speed at which Louis Lumière turned the crank.

We don't know unless we look at a schematic of the apparatus whether it includes a regulator, regulating the frame rate, smoothing variations in the speed at which the film is cranked.

So it seems likely that the juddering of the frame is caused by the movements of the frame itself, as we've suggested.

Taking in all of the action, still the shot is not a wide but a mid, and quite tight on the action. Cutting off the right and left shoulders of the two figures framing the baby, who, with the action, is the focal point of the scene. That is the attentions of the parents to feeding the baby make Andrée the focal point of the scene.

And we should include in our vectorial view of character actions the looks given by Auguste, the father, and Marguerite, the mother. The turns of head that indicate Marguerite's attention turning to the baby and the unwavering attention that Auguste pays to the announced action of Le Repas, the feeding.

We might think that there is an asymmetry in attentiveness between Auguste and Marguerite, yet whatever variations there are, the mother tending to pouring her coffee, stirring in sugar, while the father commits himself entirely to feeding the baby, there is a clear symmetry. As this slide shows:

Of course, when she leans in, Marguerite's is a more intense lean-in than Auguste's, there is more movement in it, while Auguste remains fixed in profile throughout. But what produces the impression of symmetry more than anything, more than any of the movements, which are at times visibly symmetrical, is the eyeline of the baby. She looks 'straight down the barrel.' We might say this is the feeding the film is about that makes Andrée the central character. I mean, while father and mother studiously avoid it, she gives the camera everything.

And we should keep in mind our first principle of analysis, that what happens to the characters is important. Yes, the baby gets fed, solids, refusing the too-solid biscuit, but the baby feeds the camera, which, when we recall the presence of her uncle, Louis behind it, director, producer and cameraman, makes perfect sense; but she also feeds the camera literally, at one point holding out the biscuit to it: and the camera, metaphorically this time, captures or grabs the moment:

So shall we say that the camera has some agency in the scene? Yes. I think we can assert that. Hardly to the same degree of Dziga Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera, but its own vector of view comes into play. It does so in this particular way, Andrée Lumière is aware of it. Looks directly at it, down the barrel; and holds her biscuit out to it, as if saying, look, you take it, which the camera literally does.

We can ask whether the agency the camera has is deliberate. We can suggest that it is not; but I think we have to revoke that suggestion as soon as we consider what does and does not belong to the mise-en-scène, in terms of what is put there. In this same vein, we can say the technology, the discourse of techniques, the technical discourse, also has its part to play: it has a character we can't dismiss as being irrelevant in its actions to the scene.

Whereas we know the camera in Man with a Movie Camera to be put in the scene and also to function as a camera, we can distinguish between what is context for the character or characters and what is the context for us as viewers today. What enters our time from the time the film was made. What colours our involvement, adds to our experience, and serves our desires as viewers. We are here contrasting two senses of the historical, economic and social determinations of the scene, that is the mise-en-scène, and its historicity, its embeddedness in the here and now and in our experience; its embeddedness in the there and then, in the historicity of its time, and its embeddedness in the desires of its viewers at the Salon Indien, Grand Café, 14 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, on 28 December 1895.

Here there is a distinct asymmetry, an unequalness, particularly pronounced inasmuch as we still don't know what the audience then and there thought was 'worth the price of admission.' Although perhaps you have guessed it already?

The hair, that belongs to the mise-en-scène in its historical sense, helps the symmetry of the scene as we see it unfolding.

Why is it important to distinguish between our level of involvement and interest and that of a contemporary audience? And therefore to distinguish between what is given for us in and by the mise-en-scène and for its time and contemporary audience what was put in place?

To historicise ourselves, obviously. To assert that our own view is historically contingent and, importantly, due to our contingent attentiveness to technology: that is, we not only have a different awareness of the technology, we have a greater interest in it; and this interest is historically formed. Is a product of our time. You might say it's a product of our time outside of time but one, in consideration of digital media, which is at our fingertips.

Our inner experience of this short film is shaped by forces that we take for granted in attending to it as an artifact from an earlier technical era. In other words, I'm saying that we embody our technology in the way our perception selects for it and it enters into our sensation. Our technology is as innate and inborn in us as our nervous systems and our brains. It is their further elaboration. And this further elaboration is due to the workings of desire, which is made in the time where we have a choice, of desiring to see, hear and experience what we want to see, hear and experience.

Yes, just most of the time, we consider this not to be a choice.

The experience which technology affords, the experience which it provides for us, is considered at the time to be limitless. It's perhaps for this reason Deleuze says cinema is always as perfect as it needs to be for its time.

I am again invoking the idea thinking through the technical means of expression, images and signs, that are available at the time. And the idea of the delay caused by having to go through these technical means, as it is lengthened, and turned aside, from the pure sensory-motor response of habit...

...to become one of memory and then, sometimes when it is least pleasurable, where it goes as far as overwhelming us with what we don't recognise, that is new, and that we have to go through and experience as it is thought. Thought here means shown. And, shown and thought, both are here modulating, they are undergoing modulation.

To return to our formal analysis:

At what height is the cinematograph on its tripod?

We look down onto the surface of the table, which it is not far above. So that the face of the baby, in particular is flat onto us, but the heads of the parents are slightly above. As two inclined planes buttressing a third, in the shape roughly of a pyramid, that we are familiar with from classical composition.

We also have the dynamic of the line, of the exterior wall of the house and window lintel, extending on a diagonal from behind Auguste and ending at Marguerite's head. Compositionally here, there's a light-dark symmetry of the bare piece of wall nearest to Marguerite and the dark shadow behind Auguste, the darkest in the shot against the largest light-coloured plane. Brightest in shot is Andrée's baby bib and top.

The windows mark a kind of transitional zone. They give on to an interior we can't quite make out. We can see the back of what looks like a typewriter, on a table, with a chair behind, so you could sit at the table writing, and look outside.

And we should note here the depth of field. The foreground is as sharp, as perfect, as it can be, with the items on the table; while the background is also reasonably sharp of the foliage behind Marguerite.

And we can call attention to the flattening of the shot that has been effected by the lens. And note that it is precisely this flattening that the diagonal of the house's exterior wall and lintel act against, to make the shot seem, by way of how it is composed, deeper than it actually is.

Where the reality of the garden, from the part of the table we can see in the extreme foreground, to the furthest away, the trees and leaves in the background, might have a depth of some four or five metres, the shot, once we have discounted the effect of the acutely angled wall behind the figures, seems to have a depth of no more than a metre.

We are by looking at these compositional elements starting to take our analysis into the mise-en-scène... And what can we say about it?

The most obvious thing is that the shot is exterior. It is filmed outside. Perhaps this baby has always been fed outside? But it's more likely that this is out of consideration for the lighting. That it is a technical consideration. Still, as such, it belongs to the mise-en-scène.

What else can we say of the scene, other than that it is full of the signs of contemporary life? Contemporary for the time it was filmed.

And contemporaneous with the audience who would pay to see it. I mean, the contemporary audience is not going to see a period piece. It would not look at the details of dress and hairstyle and say, looks like the 70s. The 1870s, when women's dress was much more elaborate than we see Marguerite wearing. Have they dressed up for the shoot? Possibly, although Auguste in shirtsleeves without a jacket suggests an informality suggesting a decision to make it seem as natural as possible for what is going on to go on, for Andrée to be fed en plein air, or as we say in English say, al fresco.

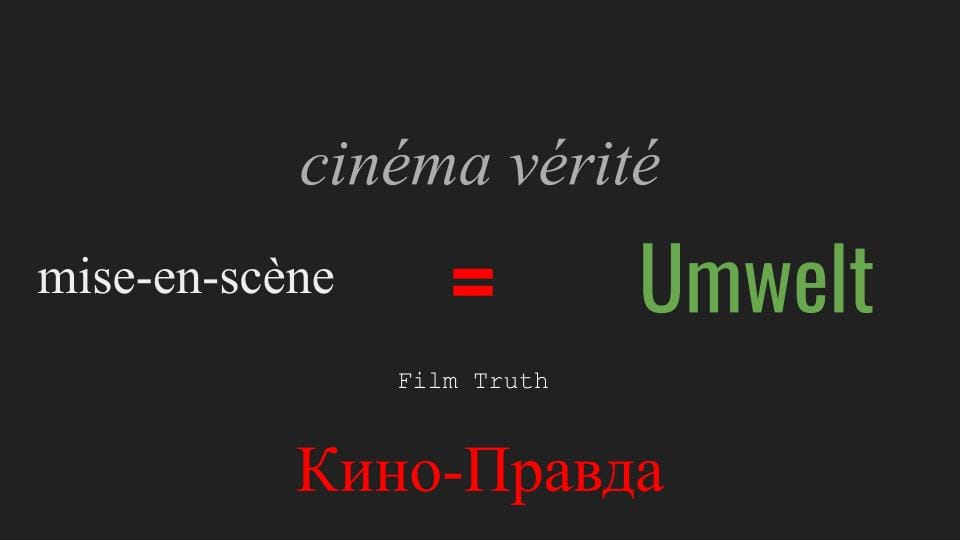

Marguerite's dress sense might appear a little too fashionable for the family at home... Still the overall effect sought by Louis with the collaboration of Auguste and Marguerite and baby, as chief subject, is one of what we call now by its French name, cinéma vérité.

A natural setting for a natural scene, or, as the inspiration for cinéma vérité, Dziga Vertov, theorised it, Кино-Правда. As we know, Man with a Movie Camera is regarded not to be so much a narrative film as a documentary, one of the best ever, for any time.

Now this is strange, because we automatically think of Film Truth, which is what both the Russian and French phrases mean, wanting to avoid any artificiality. Both in the direction of realism, to be true to life as possible.

Here the effort to animate and give life to hair and grass and smoke in the airless space of CGI, so that these move independently, the use of particle fields and so on. And in the direction of making invisible the technical means of shooting and capturing the image. The image was of nature, as was said at the time of the first motion pictures, caught in the act, which the visible presence, in the mise-en-scène, of the means of capture, you'd think would spoil.

Yet Vertov's documentary style of 'Film Truth' is overtly theatrical. He exaggerates the presence of the camera and tripod. He animates them. They are less true-to-life than life-like. And here we get a hint at what modulation might mean.

It has to do with the play of desire. It has to do with what has character. And we must think of whatever truth Film Truth, cinéma vérité and Кино-Правда has as being essentially appropriate to character. It belongs to this character, this, as Jakob von Uexküll puts it, in one of the texts I gave you to read, Umwelt.

Realism too, when it comes down to it, belongs to the world of the character. We saw this in Snow White. Von Uexküll is more radical, he says reality as well not is specific to the individual, like, my world differs from yours because of my beliefs, unconscious and conscious, but is essentially of the species of life to which the character belongs.

So we can say of the schematic kind of life of cartoon dwarves that they not only are of a different species but that their reality is too. It differs in character from Snow White’s. They not only occupy a different reality, their Film Truth belongs to the cartoonish, morphing, anthropomorphic, American speaking, character it has, of the Disney world.

For our formal analysis, we are still on mise-en-scène, on Umwelt, which for Film Truth, is what mise-en-scène is.

In light of these comments, we need to look again at the distinction made earlier between what is deliberately put in the scene and what is not, like, for example, the jumping around of the frame that is due to inaccuracy in the alignment of successive frames by the technical apparatus of the cinematograph. Because it is in the nature of the scene for it to be so jumpy. And in that jumpiness we have a sense of the character of the surrounding technical apparatus, the technical discourse, the technology, that the mise-en-scène of the world is true to. The reality itself is a fictional construct of that character, the same as the world, full of all its historically, economically and socially determined signs. The same as the coffeepot, the technology is a fact of life. And of nature.

OK, so we can again broaden our sense of mise-en-scène, not restrict it to what is deliberately put in shot, but include in it, yes, the natural lighting, the naturalness of the scene as set, the natural setting, the exterior setting, in nature, the atmosphere, a day sunny and still, good for shooting, and the technology, the technical discourse, as it is concretised and embodied in the camera-film-developer-and-projector of the Lumières’ Cinématographe. At 16 frames per second. Black and white monochrome film. Sprocket system not allowing for as smooth a shot as we are used to.

So it looks like everything is historically determined, including the ‘truth’ of the film that belongs to the historical reality of the character of its technology. It also looks like the truth and the reality are included in the fictional construct...

...but we have been careful to characterise this technology and to show how it modulates what we see... so that we might be tempted to ask is there another species of view than the human at work in the moving image sequence? To this other species the technology used to form the moving image would be specific. For 1895, cinematograph. For 2022, digital media.

Except that we have from the start said that this technological view bears on the human one and only on the human. Not as a means of representation. Other species have this. And as a means of representation we might have to say there are two species of view: and more: that there is another view specific to digital media that is not present in 1895.

No. As specifically human, the view of technology affords our species something. From the start we’ve said it was a mode of expression. And it’s also tempting to look at this technological view as an advantage: an advantage of our time over that of August, Marguerite, Louis, and little Andrée. But if it is it’s also one of our species over others living in the world now. That’s where I think we go wrong.

Biomimicry’s a big thing now. Improving jets with the smoothing effect of natural micro feather-like structures, tiny fractals, that smooth their passage through the atmosphere, creating less turbulence, less drag. Same for swimmers, high-tech togs let you cut through the water like a dolphin. Because with jets and togs we are having to take the whole technological view in, we have to ask, is it really an advantage?

High-tech production may be more sustainable, yet global production chains mean that a lot of the high-tech is crossing the world many times over, emitting carbon as it goes; or there is the question of extractive processes, the blood minerals brought up in an earlier lecture, that keep regions in the Congo in a state of siege, held to ransom by the world, and its interests there, for the sake of cellphones.

So, if technology cannot be entirely seen as an advantage, this is because it’s human. Or, as we’ve said, we have it at our fingertips. Type into a computer keyboard. It extends and elaborates on what we have inborn and innate in us: a nervous system, a brain. And a body to sense. It lets us see what our eyes cannot on their own. And if we pay attention to it, it has other potentials.

What those potentials are, in view of the moving image sequence, is what we are discussing now.

... so one species... You can probably see why we want to be paying attention to it: because some of the potentials are better than others.

...but we have no role in this ... decision. We don’t get to say what technologies get made or for what purpose.

If we think of the distinction we are still addressing, between constructing the mise-en-scène, a fiction, and what we cannot control... think of the level of control in the digital studio!... between that and the reality of a character, even of the camera as a character, we start to pay attention to the difference in our situation now, and we do this not so that we come to terms either with all the advantages we have now to make cool stuff, and not to remind ourselves of the costs involved in planetary despoliation and harm to life; we do the distinction to remind ourselves we are in history too: and here, either it is what it is, or we have choice.

That is, we go to our first lesson: historicity. The prison we make of the present moment when we think everything’s already been done, everything’s already been said, the order to extinguish all those other species has already been given. If we go there, it is not only to bind ourselves more tightly to historical and narrative determinism, the automatisms of the historical narrative, but to free ourselves too. How do we do that?

How do we most often express our unequalness?

We say I want different things.

What is that unequalness? It’s I don’t equal you. It’s also I am unequal to the situation. ...

A social situation, a relationship: we say, I want different things from you.

Sometimes it’s I want different things from you. I want you to change up. In other words, I want the narrative between us to change.

A social situation: I like different things to you. We’re never going to get along. ... Taste goes all the way from chocolate to social organisation.

In the condition we’ve called historicity, awareness of our embeddedness in time, we don’t ever, if we think about it, totally agree with our situation. Our situation never entirely agrees with us. We are not equal to it means it’s overwhelming. It’s not equal to us means we are unequal in a positive sense.

And this is what I want to get at.

I like different things to you.

I want different things from you.

The question of what we actually desire is often left open. Because we don’t know what happens next.

And that’s where choice comes in, in the gap of the ‘unequals’ sign, which is again to put it negatively. When the fact that what we actually desire... of a person is often... left open. Or when we say it the other one says, but yes I have that quality already, didn’t I... The other one interprets it. Because it’s given to interpretation. As soon as you say it you can’t control the narrative. As soon as you say what you think is going to change the narrative, the narrative changes perspective, or the perspective on the narrative changes, because it’s the other person’s.

When the fact that what we actually desire of a social situation is often left open. ... We tend to blame ourselves for not fitting it. We begin the narrative of either our identity and difference in not fitting in and coming to terms with it. Or we begin the narrative of our nonidentity and difference, that maybe we’ll never fit in. It’s not their fault. It’s just the wrong scene.

When the fact that what we actually desire of an economic setting... well, we know we want money. We want options. But what do we want of the economy? That it’s more generous and less ... economical. When we leave it up to the experts... When we say we are unable to modulate it in desire, to find a mode of economy that is satisfactory for ourselves as well as others... The fact that this is left open...

The fact that what we actually desire from technology... well, we often want it to be more open than it is. We want the surprise that the new generation of phone does something ... like levitation ... lasers ... We want the new generation to be not a new generation of phone but a whole new thing. ... We want from the technical discourse that it do more than continue the same old conversation... with the same players in control of the discourse, making the same rich guys richer... which takes us back to economy. We want from the conversation of technology that it become a dialogue, not that it shape itself, not that it mould itself or modulate itself to personal preferences, pretending that it’s continuing or reinforcing or our own personal narratives: we want from it that we don’t know what happens next...

And from history, what do we want? Is the desire left open? Or does it close itself down on the existing narratives, on the prevailing ones?

We know these stories. These we have reinforced every day. And we’re back to the narrative of either looking after the earth or looking after us and preferably both. And we can see why, here, given these givens, these determinisms, and as we have said these automatisms, that desire itself comes to be shown in a negative light: the view of psychology, of psychoanalysis, is that desire is about, has to be about, what we lack. What we don’t have now.

Our rejection, our unequalness, is separated from the earth, from its history, and from ours, by an unequals sign that is a minus.

When isn’t it the case that most often what we desire is left open? That we want to wait and see?

And what is this openness onto? What does desire open out onto? Possibility.

And that Bergsonian question, or problem: time. Is it the future when the future looks foreclosed on climate death?

No. Because we have recourse to character. To the character of our own inner experience of time. Where there’s a gap, a hesitation, marked by the unequals sign.

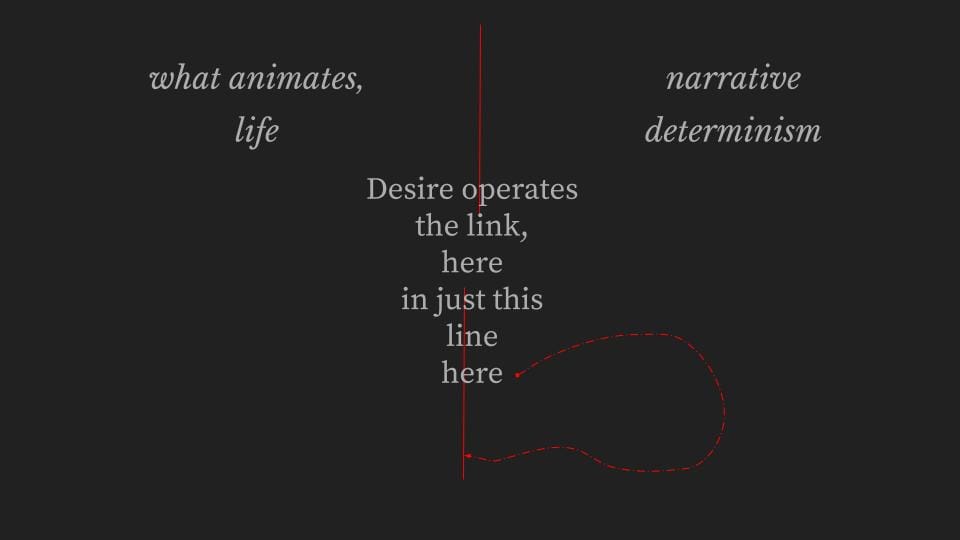

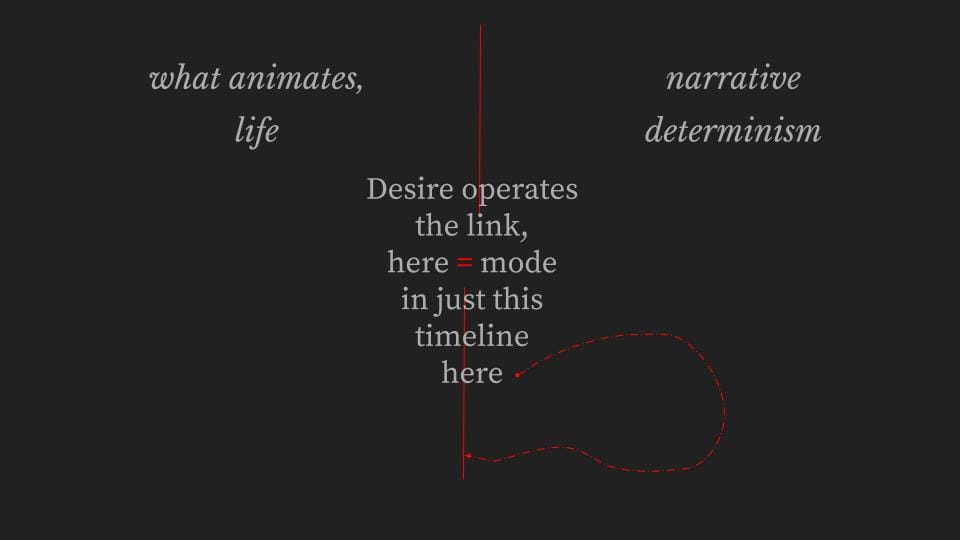

This was the minimum condition for animation, that is, life. A time that is not on the timeline of narrative determinism. Is that a negative?

No. Yes, it’s a positive: the unequals sign, the minus sign, is a link. And I am saying what operates that link is desire.

In its openness, its often confused sense in our hearts and minds of what it is we want, is a link, a hesitation, before we do what we do.

And I would also name it by this funny little word, mode.

Being schematic, between the grandly named historical timeline and the negativised inner presence of our thoughts and feelings, the link is singular.

Individual in the strongest sense of individuating, becoming... left open to what happens next, that certainly is going to matter to us, that is what we don’t yet know.

Becoming what one is, modulating.

We can now define formal analysis as, How a thing becomes what it is.

It has recourse to character, animated by desire.

And narrative no less has to, if it’s to go further than the automatisms of habit, of familiarity, of the ride the familiar story takes you on, if it is to break with that, narrative, to become what it is, also has recourse to character, animated by desire. We are coming close to saying one of those things I mentioned at the beginning: what drives narrative? Desire.

What about the other thing I started with?

Modulation.

Formal analysis: how a thing becomes what it is. But surely it is what it is. Isn’t it?

Well it can be, like it says on the label, Le Repas de Bébé, Baby’s Dinner. But is that interesting? How does that sit with our desire? And how did it with the contemporary audience, in 1895?

(Have you worked out what that audience said, Yeah, that was worth the price of admission! about?)

Any narrative has a little bit of becoming about it. As we will see, even this one.

This word modulation, a modal becoming, that has the potential to traverse habit, dig deep into memory, and fly out the other side... into the unknown: a modal becoming that is singular to that which becomes.

Because what becoming what one is really means is becoming different. Different from now. Different from now. And now and now and now.

So in the title to the first five lectures we had modes of contents and we dealt chiefly with character, but also with mise-en-scène, and different sorts of becoming and their contexts. This next series has the title modes of form. In it we are taking on how a particular form becomes what it is.

Which we can now understand to mean, how a mode that has the form, for example, of a genre piece, of a generic work in moving images, becomes what it is. And this is what the formal analysis I think can tell us.

...

So, back to Le Bébé, Andrée, and her resistance to the biscuit.

Let’s get to the bit of our analysis dealing with narrative.

What happens?

What’s the story?

We can plot it out: these are the events, roughly:

Papa spoonfeeds the baby.

Mama puts a sugarlump or two in her coffee cup, pours her coffee, and stirs it. Papa tries to introduce the biscuit.

Baby takes the biscuit.

Baby either doesn’t like the biscuit or wants to feed it to Uncle Louis, who’s behind the camera... but that’s veering into story.

Baby holds the biscuit out towards the camera. And towards us, the audience. ...

Mama leans in, then returns to her coffee, while Papa goes back to the pap he was initially spoonfeeding, smooshes it around the plate.

Who’d have thought such a lot could happen in 45 seconds!?

What’s the story?

Here we can deal with why it’s set up like this, not so much in view of the mise as in view of the story: what story is Louis, with the help of Auguste and Marguerite and bébé, trying to tell?

It’s a domestic scene. One which has been taken outside, to satisfy, we can imagine certain technical requirements, like sufficient light.

Auguste and Marguerite have been directed to be as natural as possible. The scene is supposed to be as natural as possible. They are told not to show that they know the cinematograph is there, Louis cranking the handle, the sprockets clacking in and out, while Andrée is not of an age where she can take direction.

After all, she won’t even commit to the biscuit.

And Andrée is the interesting one here, the point of interest, the focal point both for the story Louis didn’t intend to tell and for the one he perhaps did.

The one he didn’t interests me because I see Andrée feeding the camera, perhaps what it doesn’t want, but what it gets. And I see this story as about feeding the audience, therefore, with what the Lumières think that they want.

So it comes down to a matter of is this story about the baby’s dinner? Or is it about the biscuit?

Does anything else happen in this forty-five seconds that might ... take the story somewhere else? To an unknown point?

There’s the juddering of the frame. There’s surely a technical story there. A story about technology and historicity.

Anything else?

What might we want to add to this piece of early cinema, of motion writing, that would increase our interest? (Unless we are already fascinated with the baby-feeding habits of the bourgeoisie in late nineteenth century France.)

We could throw in a cat.

Or Louis could. Have a cat behind his back. Chuck it in.

Mayhem.

In other words, we can easily imagine an accident shaking things up and turning Baby’s Dinner into, for example, a funny cat video. But then it would just be dropping out of its perfect formal achievement and participating in a genre. Where it might be judged ... not the best funniest-ever cat video.

Or could we TikTok it?

Again, falling into the habitual. The familiar. The recognised.

How could we help this work become what it is?

...

There is no helping it. It doesn’t need any help. And the audiences who paid to see it didn’t think it needed help either.

Cinema is as perfect as it needs to be, as it can be, at the moment.

So we wouldn’t be improving on perfection, by throwing in a cat.

...

Another way of asking these questions is to ask, What drives this narrative?

Phew... difficult to answer. Not Papa’s desire to feed the baby. Not Mama’s desire to drink her coffee in peace. And not really Andrée's desire to give Louis the biscuit.

I think we’d have to say the drive is technical here. It is motoric. It is to show this can be done. And to show it to an audience who will pay to see a normal French family of the time feeding their baby.

...but...

is that what the audience saw? Did they see technical achievement? Or were they too busy watching the scene unfold to notice the technical means of its achievement?

What story did they want, in the end? What interested that first paying audience? ...

Have you got it?

...

We shouldn’t get the wrong idea of desire here. It’s not what the audience wanted to see that they afterwards felt satisfied having paid to have seen. It’s what they were shown: what projected onto them, not what they projected onto the screen.

Desire, we should remember, links. It’s not a lack: Oh, I wanted that, meaning, I wanted for that.

Desire produces a link between the time inside the viewer and the time inside the viewed, the given time of, for example, 45 seconds of film.

So we might as well say, what effect did this 45 seconds have on the audience of the time?

We might as well say, what effect did this 45 seconds have on the audience, as long as we don’t attribute to it a cause.

The cause is not found in either the audience or in the piece of film, the moving image.

It is between them. It modulates the two. The other name for this link has been character but we can also call it, we have also called it, affect.

It is what the audience feels. It is also what the image shows. And, we’ve also said, what it thinks.

It goes between viewer and viewed. It goes between the zone of indeterminacy of a character’s I don’t know what’s going to happen next and the scene given in history, at the Salon Indien, Grand Café, 14 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, on 28 December, 1895, where we are interested in the audience’s response.

Did the Lumières get it right? Was the dinner a smash hit? Was Andrée a star? ...

Desire is always open. It just gets covered over with automatisms, determinisms and habits. It gets covered over with the familiar and the recognised...

So what we should note about these two time zones linked by desire, one a zone of indeterminacy, one determined, by history, social setting and economic setup, is that they are unequal.

We noted it earlier and said it was a positive, good thing. Not a minus but a plus.

And we might note the same thing about the unconscious: that un- at the start of the word conscious doesn’t make it negative. It doesn’t form it into the binaries we saw in an earlier lecture, of Kant’s schematism, opposing light to dark, object to subject, matter to memory, what is feminine to what is masculine, and, by extension, consciousness to the unconscious:

what sort of zone do these distinctions belong to? Not our zone of indeterminacy, of phase space.

Desire links both narrative drive and modulation.

It is the open-ended answer to the questions I asked at the start.

What do I actually want, in a person, a piece of work, a home? is the question we close over out of habit: because too much indeterminacy is difficult to handle. Which is why we make recourse to character and the open possibility that a character faces when they don’t know what’s going to happen next. That hesitancy...

... and the vector of their action of which they are the expression...

... because all a character needs to be one is connect from the determined or predetermined sort of time—for example, of the Hero’s fate—to the time of reflection—when the Hero considers whether they are equal to what lies in store: in, yes, a sort of opening up to it. That is, wanting what comes whatever it is.

Think of the tragedy of the tragic hero... knowing it’s going to be bad but choosing it anyway... is this any different from heading down into the abyss?

Yes, it’s covered over by the familiar. ... Until the accident: and onto us is forced another time. Our foot dangles over the precipice. We see our whole lives pass before our eyes. Or time slows down.

That’s exactly how modulation happens.

So, you can add another tool to your formal analysis, modulation, how a thing becomes what it is, singular. A mode of form. Of expression.

And you can add modulation to the formal analysis of your work too, by asking, How do I let what I am working on, whatever it is, a love-affair or an academic essay, become what it is, singular?

...but wait: how does that happen, again?

By finding in it the operator, that operates the link between the given and the possible, between what it is and what it can become. For character we said character always has the character of a who, a she, he, they; never an it.

For a modal becoming, which we know simply means a singular becoming, the operator, the link, the minus that is positive, is a that. And it applies to a time internal to it.

For there to be narrative drive, we can say and see it’s the characters whose desire drives the narrative. But what about the narrative that is so familiar, so ploddy, as exciting as one-foot-in front-of-another, without any falling down, ... until it comes... Yes, the accident. That’s one way.

Why does the accident occur? Character didn’t see it coming.

And we can say the same of the incidental, that we didn’t see coming, that is, for example, an automatic result of making a film.

Another way: making a vase like a character. Like in the Ozu film:

This singularises it. It can no longer be any vase, it is just this one, occupying its time as this time and no other.

So we have the word mode. For how things can act like characters.

And make this general rule: things act like characters when they stop.

Stop working. Stop working to drive the story, the love-affair, the academic essay. Reflect.

When we reflect on desire, we realise we don’t really know what we really really want. But we are sure of one thing. It’s outside us.

This outside is in a time to come.

There is formal identity that doesn’t have this sense of modulation in it. An identity that comes from difference, as we can see from the unequals of desire. So modulation is a self differentiation. And shows the working of desire that is no longer held captive in persons, identities, or personal identity.

And we can see this in Le Repas de Bébé, when we take this new tool of formal analysis to it: what did an audience see in this early work of cinema, of movement writing, that differed?

What difference did they applaud, and say, That was worth the price of admission to see! ?

Remember, they went to the salon of the café that day, which just means the room in the café, not knowing what they wanted to see.

And what did they get? Mostly what they knew already. Most of it they were already familiar with. There might have been one or so nerds in the audience that day who weren’t looking at the images but looking at the technological marvel of them being there. But on the whole, the audience looked at what was going on, that the formal analysis of the narrative has shown us.

And they found in it... nothing at all miraculous. They didn’t have to excuse the jumping around of the frame or make allowances for it: they’d nothing to compare it to, so it made no difference.

What did? What modulation is at work in the form of 45 seconds of celluloid passing in front of a strong light source?

“the leaves on the trees are moving”

...because that’s the other way modulation can occur: the different sorts of time are in the image itself: the motor-sensory time of the technical apparatus; the habitual time of what we can take for granted, of a baby’s dinnertime; the memorial time, to which the spectators matched their own experience of just such an unstoried event taking place in their own backyards; and the time of nature... that fractal zone... attracting the eye... the eyes of the audience like feelers... extending into it... feeling the leaves moving... the leaves moving on their own!

The mise-en-scène offers its own mode of modulation in this otherwise natural occurence, leaves moving. The mise-en-scène becoming a character, a vector of action, that is not motoric and not in any memory of the cinema before, but is shocking because of that.

And breaks with habit in the softest most reflective way... And calls on the audience to reflect on their desire... now open to a new possibility in the conditions of life...

Who delivered this to them? Not a character, an it that is so singular to the image. It is a mode. And what happened from this modulation of form we see that they saw?

An entire genre of film was born. One that’s not talked about much at all because it seems so unremarkable.

What is really remarkable is that this genre, which is the first ever genre, in a fact that is never remarked on, has come back to us, a hundred years and more later, in the minimalism of ambient film-making and slow TV.

The first ever genre: The Wave Film.

... yes, I know it’s not the Leaf Film or the Smoke Film, which were both effects impressing audiences at the time, leading them to say, That was money well spent! But you can see how the Leaf Film leads to the Wave Film, and to further modulations of this genre, such that audiences were wont to compare the qualities of the waves in different instantiations of the genre: that is, they compared different modes of contents in the differing modes of the form.