moving image: theory | context: lecture 8

With gaming it feels like we take a step back... from the multimodality John A. Bateman attributes to digital media.

Bateman’s research engages multimodality in representation. We are interested in multimodality in expression. So our definitions, in particular our definition of what constitutes a mode, differ.

Bateman finds the digital artifact to be multimodal for the reason it uses multiple or can use multiple modes to communicate its meaning and or its information.

The distinctions... I am using his example to clarify the terms and for the sake of contrast with the kind of theoretical understanding we have been building over this course of lectures... The distinctions he makes are between:

medium

genre

and mode

And in the plural:

media

genres

modes

It’s really the plural of the first one we should be attending to, because we are used to thinking of the media as a bloc: what’s in the media? What have the media said about it? Who has control of the media?

This last question is important, because when the media are blamed, it is them, the journalists who are taken to task about what has been written, what pictures have been published, with what slant to them.

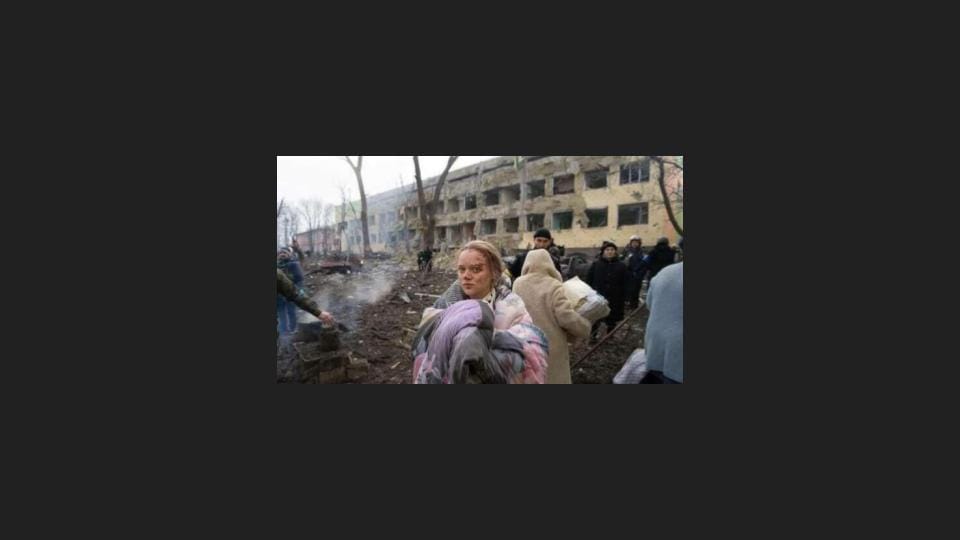

For example, a pregnant woman in the hospital recently bombed in Mariupol contests the story given in the media that the hospital was targeted by Russian forces, and women had to be evacuated, pregnant women, wounded, some unconscious... She maintains that Ukrainian forces entered the maternity hospital and kicked out the patients. She was transferred to the only other maternity hospital in Mariupol, where there was no food. Local citizens set up camp kitchens in the street to feed them. Then Ukrainian soldiers came in and, because they’d had nothing to eat for two days, they took the food.

Her story, which she said was confirmed by the Ukrainian forces on the ground, was that there had not been any Russian airstrike on the facility.

And when women were kicked out, foreign press agents, the media were there to promote the story that there’d been a missile attack on the maternity hospital by the Russians.

The follow-up story was that one of the pregnant women later died.

Here’s the woman here who told the story:

This is a Reuters photo. Reuters is supposed to be one of the most dependable news agencies in the world.

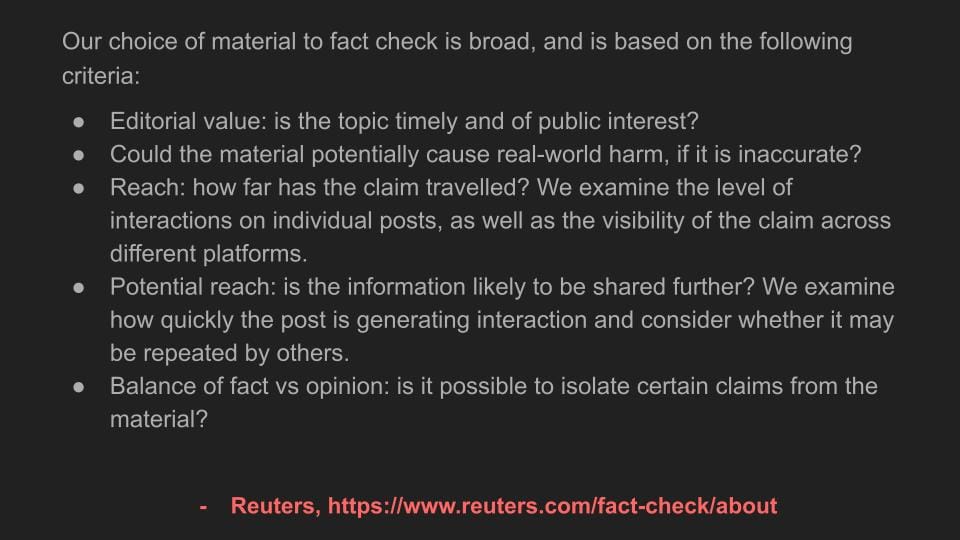

Here’s Reuters fact check policy:

- Editorial value: is the topic timely and of public interest?

- Could the material potentially cause real-world harm, if it is inaccurate?

- Reach: how far has the claim travelled? We examine the level of interactions on individual posts, as well as the visibility of the claim across different platforms.

- Potential reach: is the information likely to be shared further? We examine how quickly the post is generating interaction and consider whether it may be repeated by others.

- Balance of fact vs opinion: is it possible to isolate certain claims from the material?

...

Head of their Fact Check unit is Hazel Baker who holds a Master’s degree in Online Journalism from the University of Central Lancashire.

Do we blame Hazel Baker of Reuters’ Fact Check unit? Do we blame the journalists on the ground, who, we are told, by the woman in the front of the photo that was published worldwide... well, not worldwide.

It was not published in Russia.

I don’t know. It might have been, with the opposite story...

…but surely the Russians wouldn’t stoop that low? to say the Ukrainians staged it for Western media. ...

Do we blame the journalists on the ground who, we are told, staged the photo for Western media? ... Or do we blame Reuters?

We call out Reuters by name. We ask for Hazel Baker to speak for her Fact Check unit. What can she say? She wasn’t on the ground?

How can she possibly know that one witness will come forward and claim she was there, pregnant, a little cut up on the face where the glass showered from the windows, because the airstrike had at least to resemble one, see the unconscious pregnant woman who later died, and further claim Ukrainian soldiers, who took the food from camp kitchens, citizens had set up for the women at the second, smaller hospital, to which they were evacuated, out of their mouths, told her there had been no airstrike?

Having already seen journalists asking the interns carrying the unconscious pregnant woman out on a stretcher, and herself being positioned at the front of the shot, to get the story...? How can anyone know who wasn’t there?

Well, isn’t that the role of the media? Let’s look at those claims of Reuters.

Nowhere does it say, The correct representation of the facts.

No. But it’s not Reuters' fault. They were not Reuters people on the ground, those journalists. The ones who were paid by Western media for their story.

Can we blame them? Yes we can. But they were risking their lives to get the story. Then we blame the ones who gave them the assignment. And the assignment brief-givers.

You’re not going to risk your lives for the next assignment. But you’re at least going to try to follow the brief. Just to be clear: what was their brief?

Aren’t these journalists who staged the event that made it look like the Russians were responsible, for an airstrike on a maternity hospital, soldiers in the war of information?

This is where we circle back to the nature of medium again. To inform. For Reuters to also have an eye out for “Potential reach: is the information likely to be shared further? We examine how quickly the post is generating interaction and consider whether it may be repeated by others.”

Note also, in light of last week’s lecture this question, under the heading, Reach: “how far has the claim travelled?”

It won’t have travelled far when it hits your eye. And I have not shown you the video footage. Because it is of the pregnant woman, unconscious.

It will have engaged your eye, and will do more, now that you know the woman died. It’s all right. It’s not gruesome in the sense of there being blood and so on.

Its impact now is greater than when it was initially broadcast, because we know she died. But for me, it’s gruesome in another sense: events staged for the war of information, like in any war, can and do end in death.

This question of distance: the claim that a Russian airstrike ended in the death of a pregnant woman ... is powerful enough ... to put any other questions aside ... if you can show the moving-image sequence showing it. Showing all of the circumstantial evidence.

You might say, we want to believe it. That’s why we do. But more than that, there is actually no distance for the claim to travel if it’s on your screen. If it’s on your screen, and if I showed it to you now, it’s right in front of you. Happening. Happening when? Happening in cinematic time.

...

Media inform. Entertain. Instruct. And so edify. That’s the classical strategy. For the medium of performance, actually.

Our predominant understanding of medium, singular, tends to be that it is neutral. A neutral channel for the passage of information.

This neutrality can be held up to scrutiny, sure. And Bateman allows this, by invoking the semiotic systems which, in any particular case, make meaning. That is, the systems of signs which make meaning.

So that we can say the dollar signs from Western news agencies enters into the semiotic systems of the journalists staging the story. If it is indeed the case it was staged. Doesn’t matter, the medium is neutral.

This neutrality of medium is achieved by the system itself, because what considering news channels the same as any other medium, that is, the media, same as any medium, to be a system of signs allows is neutrality. The signs are not what they say. And this is entirely what Bateman intends, not that the signs are not what they say, but the neutrality of medium.

Since his analysis, which goes to multimodality, that we will get to, is intended to be science, Bateman’s interest, what we may call his speculative interest, is in keeping clear of the war of information. Just like science is clear; or sport is clear of politics; and the speculative interest is an innocent one. And we know this to be a hard task, given the culture wars, the coordinated campaigns of which have grown up and become distinct from political correctness. Their primary medium or ground, or battleground are social media. A whole other set of media.

And sometimes we hear talk of the fertility of those grounds. Like Twitter for the #metoo campaign. Where they grow. As if there is something in these semiotic systems, however neutral they are, these particular ones, that allows for them. The question we ask here is, Do they as systems transmit the signs? for example the hashtags? Are they simply for their transmission? Or do they somehow produce the campaigns of the culture wars?

Are the signs as much the products of the systems as much as what they say?

How do we answer this question? We can return to our example, the video, part of the information war that runs in parallel with military campaigns, military campaigns which are the product generally of national interests, which shows what may or may not be the aftermath of an airstrike by Russia on a maternity hospital in Mariupol, one woman in the foreground, her face really cut-up, who later as an eye witness said it was staged, about whom it was also said that she is a ‘crisis actor,’ not for real at all, and another woman, lying on a stretcher, who later died.

I will not show the video, but what I want you to do is imagine it. Imagine seeing the first woman, clutching her bedding around her in the still shot as we see, her face cut up, and then seeing an unconscious woman carried forward on a stretcher. Perhaps you can put aside the knowledge she died.

There is no distance at all. You plug directly into the scene. It is one shot. But it’s not that that engages your attention. If you pay attention to what you pay attention to, it’s the irresistible feelings that come from watching something that is happening and unfolding as you watch it. You experience it as you are experiencing it.

Insert a system. It doesn’t do anything to the experience. It comes later, perhaps following a speculative interest in overturning the idea that media or any medium is neutral. But that is not the point here.

The point is, you plug yourself in to cinematic time; or you are plugged in. Why is this different from another medium? Well, for one thing, it’s social. It’s shareable.

You can read a story on the front page of newspaper, where, as used to be said by newspaper editors, if it bleeds it leads, so goes on the front page; you can read a story there, online if you like, click on the hyperlinks, enlarge the photo, read the text; and you can copy the link to send to your friends or to post online... but, in what Bateman will call this multimodal form, you leave for all those you send it to so much time at their command. They needn’t read the whole thing. They can stop at what Bateman calls one mode, like the text, and just read the headline. Or look only at the picture. Another mode. Or follow a link, another modality digital media offers, to establish backstory. Go to the comments. Look up the author’s name. Search out the sources for the story. Establishing in their own minds, not necessarily what the story’s about, what the signs say, but what your intention was in sending it. Does it fit with their beliefs? Do they need to ghost you now?

While send the same friends or post a link online to a video taken outside a maternity hospital in Mariupol.

No. This doesn’t place them in the time when what happened took place, or even, if it’s live, like this lecture, it doesn’t place them at the time it is taking place. You might say it’s unfolding inside them, that experience. Cinematic time or screen time commands the time of its experience.

That it’s shareable and that social media of different types make sharing media of different types easier or harder is secondary. The social side is secondary. The difference in the medium of the moving image is this time factor.

...which is not even the time it takes for the moving image to play! Because it can be edited, intercut, jumpcut, shortcircuiting the time it takes, repeating, going slowmo: the shot is available to every sort of permutation, after the fact of what makes it a medium, the mystery we invoked in the last lecture, or the aura of it: to start time. To originate time. Each time. And what this means for experience.

So what in Twitter gives rise to campaigns that are more or less compelling is not the shareability of the content and not the non-neutrality of the algorithm according to which it is selected but it’s recourse to time. And with that, we have jumped directly to mode. The mode is like the character in that it connects to another sort of time. Important: it’s not another form of time. It is a mode of

form. Singular. Unique. And repeatable.

In the form of the shot, potentially subject to every sort of permutation.

We have overshot genre, but have we said all we need to about Bateman’s notion of medium?

Let’s briefly recap. Medium is represented for Bateman, according to his speculative interest, by the semiotic system. This system of signs that are not what they say is said to be neutral in another system of signs.

And so on.

Transmission? Or production? Semiotics can be radically inclusive. The semiotics of Facebook can include the prompts it gives to produce data, share links, and photos, and what it calls ‘events’ and ‘experiences’ which are simply more data. Can it account for this singular compulsion to share?

Semiotic analysis would have trouble coming down on the singular, singularising that particular connection linking you to what you have posted which is the reason you posted.

A performance analysis might not face this difficulty. It could point to the separation between your actual living self and the picture of it you’re showing in what you post. Doing so would be to evoke the notion that you, like many users of Facebook, Instagram, and other social media, create a character. That you use social media to create a character. In more or less conscious ways, that you perform. You perform this character and you perform on this digital platform.

And I would say the separation, whether or not it is a conscious one, between our selves as we are and our characters is automatic. An automatic effect of the digital platform, whatever it is, which we only later try and recuperate by character creation.

That is, after it has happened, after the time of the online avatar has split from the time of our own living inner experience, do we try and assimilate to ourselves and try, to the degree we are conscious of it happening, to control it, by assuming the character. We then assume the character it has presumed.

And what has presumed for us this split? The mode of time we enter as soon as we initiate it in the moving image. As soon as we enter screentime, we are not ourselves, so it forms our inner experience ... which it lets, in Bergson’s beautiful phrase, “reel off ... into action or wind[s] ... up into pure knowledge.” (Bergson, 2021, 101) Pure knowledge here signifies the cinema of contemplation.

That this happens ‘as soon as’ we enter into our engagement with screentime means it’s a matter of habit, and its power is as a habit. So that we don’t think about it anymore. And we are not given to contemplating it. Like, I said, in the last lecture, a dream, a dream reeling off into action, or winding up... It also means amounts of time given to screentime don’t figure as measures of its actual time, because, in a single cut, 2.6 million years.

To perfect the image then might mean something quite different than perfecting the dream.

And if it is all that is left to do, that might mean something different too. Rather than having to wake up, it might mean we wind up into pure knowledge our inner lives and not reel them off into action. Not to wake up, but in the inaction of cinematic contemplation, in the time where we have choice, we are able to pass through the dream.

...

What the first audiences for moving image were doing was cinematic contemplation: it was shocking and then compelling to see the leaves were moving on the trees, the waves that were crashing on the rocks, the smoke and clouds billowing up... And they sat with these images on repeat, savouring the details, and they came back to see them, as we have said. So that the first genre was not Action, but Wave.

Putting this genre first makes an entirely different history of the moving image. It goes from the desire of audiences to see waves and other chaotic forces, not controlled, but initiated for direct experience, where we see the invention of cinematic time, of screen time, through to the Slow or Ambient Films of today, and Slow TV. It also modulates, modulating experience, and replacing inner experience.

We also see cinematic contemplation in characters and modes. So it’s not limited to being boring.

Starting from the accident of how things move in real life we stay in the time of the accident by the fact that characters don’t know what’s going to happen next, and by the modes of screen time itself, at its most basic, the mystery of the shot. Modes and characters link us to what is unfamiliar, accidental, and overwhelming in the shot, its temporality. Achieved in the age of mechanical reproduction.

...

Genre enters into Bateman’s analysis; it is its insufficiency he is interested in: and genre seems for us part of second nature. Many of your assignments for short film named the genre of your film.

I got sci-fi and thriller, action, adventure, horror, fantasy and family drama. Even relationship film.

For Bateman, the traditional genres are insufficient to the mixed modality of the digital image, particularly in its appearance in online media. And, it’s true, we have spent our time considering the relatively stable corpus of film and cinema.

We’ve not looked at the post, for example, that contains a hyperlink... funny, we just call it a link now. It’s lost its hype. ... or the 101 genres that I found in a long list of different types of digital content online. At the site, Zazzle Media.

These different types or genres include memes and infographics, videos, product reviews, those written on your own blog or timeline, or on a site like Amazon; contents you generate yourself, on an existing platform, or on your site, as part of your blog or vlog; how-to guides; I would add unboxing videos, which are fascinating; live chats, live video, photo galleries, link pages for pages you recommend, case studies... testimonials... research and data... building an app... GIFs... we’re only at 25. Giving kudos for a brand or company you enjoy. Podcasts, of course. Timelines on Dipity, a recommended source for creating this type of content, says Zazzle... All the way to Flyers and Wikis, numbers 100 and 101 respectively.

The reasons Zazzle Media gives for why you might want to are these:

To entertain, educate, persuade and convert. But I suppose the reason you’d really want to do any of these things is to raise your profile as a content-provider in and for the media, digital media; or, as a really early satire on this kind of thing, Nathan Barley put it, to be a multimedia hub:

- Nathan Barley, 2005

2005. Same guy who did the Black Mirror series, Charlie Brooker; and Chris Morris: who were responsible for a completely new style of comedy. Sometimes called ‘horror’ comedy, blacker than black.

- Jam, 2000

- Jam, 2000

Are the types of digital content Zazzle Media lists, from memes to Wikis, genres? Here’s the definition Bateman uses, from John Swales’s Genre Analysis, 1990:

...“a genre is a class of communicative events that share a recognisable communicative purpose, that exhibit a schematic structure supporting the achievement of that purpose, and which show similarities in form, style, content, structure and intended audience.”

I should use the Latin tag ‘sic’ here, meaning ‘so’ or ‘thus,’ to indicate that I am quoting Swales as Bateman quotes him, with, if not the grammatical mistake in the first line, then the ambiguity: “a genre is a class of communicative events that share.” The events share, but as a singular class

of events, plural, that class shares. In that case, the definition reads: a genre is a class of communicative events that shares a recognisable communicative purpose, that exhibits a schematic structure supporting the achievement of that purpose, and [is a class] which [altogether] shows similarities in form, style, content, structure and intended audience.

What this brings out is it’s a class that shares with itself, exhibits a structure throughout itself supporting the same purpose, and so shows similarities to itself, in form, style, content, structure and intended audience.

I suppose all we can take from this is that a genre is a class of communicative events.

Yes, we can say that the 101 types of digital content do share and support the same recognisable communicative purpose, that, as Zazzle puts it, is to entertain, educate, persuade and convert.

However, these, although using digital means, do not show similarities in form, style, content, structure and intended audience.

This is because digital media are capable of being so many things, going well beyond the 101 types of content.

Digital media are, as we know, capable of including all of the hundreds of genres and subgenres of preceding analogue media: of film, music, the visual arts and literature. Including, in fact, all of recorded media and virtually every cultural and creative content: this is within the capability of digital media.

So can genre have any role here at all?

What about genres as ‘communicative events’?

Is it as communicative events that games fit into genres? Not really.

Gaming splits into conventional notions of genres according to the conventions of the moving image tradition.

That tradition bridges different media, both analogue and digital. It goes from written media, to cinema, to fully digital animated features, where genre seems more at home than ever, and more generic. For example, in Disney Pixar co-productions of the fantasy-romance genre or sentimental comedy romance, with a touch of the musical, like Frozen or with a bit of adventure, like Toy Story.

And these cannot truly be classed together as communicative events.

They are as a class entertainment events. Each one the entertainment event of the year it appeared in; or, like Elden Ring, the fantasy gaming event of the year.

Genres are in fact medium-agnostic, like we say in computer coding platform-agnostic

...but it is not for this reason Bateman finds genres and genre analysis insufficient.

The reason for him, and there are many theorists who think that genres offer explanatory models without themselves needing to be explained, that genres are insufficient is due to their being overcome by the modes of communication that rich digital media combine together.

A game may be such a work that is media-rich for using many different modes of communication. In Bateman’s view, it cannot be analyzed according to genre; genre analysis is insufficient to the multimodality of the media-rich work.

Going back to Swales, the problem is the plural versus the singular: a single class for many different communicative events.

The problem is that genre is assumed to be self-similar and homogeneous; more than this, it is intended to resist heterogeneity:

...how it does this, how it resists the threat of heterogeneity, is give birth to new subgenres, which are considered separate, and so considered separately.

The subgenres grow up, and, if they acquire popular support, they become genres in their own right, that, with sufficient maturity, have their own subgenres.

So genres are exclusive classes of communicative events, and, as we indicated in the last lecture, can have cult-like followings; genres can be like cults for those that follow them: their followers argue over whether certain instances belong in their favourite genre. Their analyses are often more in depth than any critical theorist. And more detailed.

Think for instance of Horror aficionados. Or B-Grade movie lovers, who will argue over whether a certain work might be too good to belong to the genre they love. In fact, a lot of genres are loved more for their weaknesses than for their strengths; many are loved because they are such tiny exclusive subgenres, and not part of the popular mainstream, so that they become like private cults. A few friends will guard their secrets, and expel interlopers and resist the impulse to popularise their favourite genres.

This is obviously why genres of not-good work often get more love than generally recognised good work. Because with the not-generally-recognised-to-be-good there is less risk of mainstream awareness: the cult can stay underground.

It goes the other way too, the truly great becomes the province of a select few who have access to its secrets: the truly great and the truly difficult works, as in ‘difficult to understand.’ The more difficult, the less likelihood the masses will get into it; this is often why we have critics, not to explain the difficulty to the people, so that they might enjoy it too, but to massage and inflate it, so encouraging those considered the true artists to aspire to even greater difficulty. In other words, this is the art market.

What drives these cult-like activities situated around genres? Commercial interest and resistance to commercial interest, for those in the underground, obviously; but also the desire to organise socially around the works that are loved, that are loved especially when they’re bad.

This is what we saw in the early stages of the development of moving image: a commercial incentive coupled with what audiences want to be shown. But genre sort of blasts this apart, putting the social effects before the money, in the way that schlocky film buffs don’t want their favourite artists going mainstream; they don’t want those productions getting too much money, because it would spoil what they love in them: their cringey appeal. Their make-do approach. Their lack of polish. And the lack of ego, of I’m just in it for the money and or I’m just in it for the Art.

...

So genres see a lot of action... and Romance... and Horror... and so on, but for Bateman they are insufficient to multimodality, insufficient as theoretical models for what’s going on with digital media, because of the number of channels the digital medium can handle at once.

If we think of a game: it can have text; the text can morph into landscape; the landscape can become interactive. Not only the fluid merger of one thing into another, but multiple channels can coexist on the screen at once: and, note, this applies only to the screen. Text. Image. Still image. Moving image. Scenes with mise-en-scène, diegetic sound, soundtrack. Manipulated images, texts and symbols belonging to different symbolic registers, codes, icons, indexes, and their ability to morph as well as merge, to appear and disappear. As well as their button qualities: to link to other content, from anywhere within the screen:

These channels are what Bateman calls modes: and also note, Bateman’s interest isn’t only speculative.

As speculative, the interest arises from close observation of the phenomena of having many channels, the multimodality of digital media, in order to describe them in a scientific way. As information.

And from this, information, we get the other interest: in design. In design techniques that benefit the medium, that is the digital medium, as, itself, a channel of information.

It cannot be too busy. Timings must be right. The story must be clear. The intended audience must be directed towards the intended outcome, or outcomes: to entertain, educate, persuade and convert.

Control must be exercised over the representation on how it modulates.

We are familiar with these sorts of constraints and determinations from our discussion of narrative... and to an extent you might say they fall back into genre, into considerations of what genres stabilise as being the right ways to go about things, the accepted ones and the known.

But this isn’t why we are here concerned with Bateman’s multimodality. We’re not worried about the theory and analysis offered by multimodality not escaping genre.

What concerns us are circuits of indetermination: how images think; how the moving image thinks.

For this reason we have focused on film. On cinema. Why? Does this, what we may call, medium, epitomise the moving sound image? What about other forms? What about gaming? Or the fact digital media can assimilate moving images and sound images into anything? Making the media-rich artifact, or, as Bateman says, becoming multimodal?

Is it because film, cinema, constitutes a stable zone? lets us ground our thinking before going to the more complex digital forms of, for example, gaming?

Our focus has not been on the relative stabilities of communicative means, in media, on iconographic and other repertoire, in genres, or on modes of meaning-making, symbolic, pictorial and representative, and so on. Bateman’s multimodality is a reminder of the instability we find first in the earliest moving images and in the genres that involve and pursue and express it. And in the media that are not for us about communicating information, but are its means of expression. That instability comes from unequalness that we attribute to desire: both of audiences and of the interests producing moving images, games, VFX, video art, and all those we named at the start modes of expression.

We have focused on the earliest instances of film for the sake of considering modes of form, which are always actively unstable because always modulating. From the start, we might say: from when the reel begins to turn. The pixels begin to dance.

…

Now, we have been saying a mode is individual in and out of the shot: modulation is how it becomes what it is.

The shot being the most basic element of the moving image.

We should add that the shot is not a visual component but a slice of time. Of chaos. And includes other perceptible elements like sound.

In the shot, how do we know the mode is individual? Because it originates each time.

This was Benjamin’s idea of the aura, which is lost, without a sense of loss. Since it is regained each time.

The proof of this, the mystery of the shot, was for early audiences for the moving image in chaotic, random, chance effects. Leaves, smoke, waves.

The first genre isolated this proof, which could then be compared: originated each time the clip played, the wave…

…could be studied. The same wave. In every detail the same. Amazing. Of what was it educating? persuading of? It certainly was entertaining. And converted new audiences to the medium of cinema.

Then in the next clip, a new wave: I like it better! It was bigger! Did you see the way it splashed on the rocks? And sent billows and clouds of spray up into the air…

So knowledge builds up from the comparison of the wave to itself and of the wave to other waves. What was represented? What was the subject? It was just a wave. And that was enough, for the moment, it was perfect.

Genre.

Genres are not containers, like Bateman makes them, multimodality busting out; they are themselves contained.

This has to do with their relation to knowledge, which they express, which is then used to suppress.

Suppress what? modulation: knowledge is, if you like, the medium of genres…

We’ve said it was of differences in how the mode, waves, modulated and became what they are: great piles of chaotic water, cresting, foaming, breaking, sending up great billows of spray… They are waves. And can be compared by audiences for offering, after the initial shock that a chaotic movement in time can be repeated, its aura re-originated, this recognisable fact, of being a wave.

In this fact are involved all future genres, which recurrence is called a ‘trope’: the moving image works of a genre share iconographies, techniques, settings, themes, musical motifs, characters and stars. Certain studios come to be known for specific genres: Warner for gangster films, Universal for horror. And MGM for the musical. Or Riot Games for the Multiplayer Online Battle Arena game, League of Legends.

These shared features of genre, iconography, techniques, settings, themes, musical motifs, characters and later stars, whether in the shot or making it, star companies and studios, and individual auteurs and artists, constitute a knowledge… that means, in a RomCom we know what’s going to happen… and can savour the details that are its modes, or the performance of the actor playing the character who doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, which is also a mode; performances are modes, each individual, unfurling like leaves in the shot; a knowledge, like following Tim Sweeney, developer of Fortnite for Epic Games.

Modes express knowledge. They don’t represent it. Just like a wave does not represent, what? Neither does it represent the time it takes nor information about fluid dynamics and gas fluid solid interactions, or tidal and climatic information. Neither does Grand Theft Auto represent; it is itself the expression of the modes of gameplay involved in it.

The whole thing comes down to expression or representation.

Gaming is genre par excellence, because it’s about acquiring knowledge.

The acquisition of skills can occur pretty easily. This knowledge must be reeled out directly into action. Like reflex-action.

The difficult bit is directing knowledge into ‘correct’ action in the immediacy of the moment.

So you see, I side more with the ludologists, whose debate with the narratologists we will be discussing in the tutorial. Ludology, the discourse of game-play, puts the rules of the game before the narrative dimensions of game-play. Narratology puts the narrative nature of games before rule-based considerations.

Both ludology and narratology seem to me to belong to notions of communication based in representation, rather than in expression: where you, the players, are plugged directly into what the modes of the game express; whether it’s in the mode of rules or new action skill-sets.

…

At the start, I said that with gaming we take a step back from the multimodality John A. Bateman attributes to digital media and this is to do with the plugging in to a game of direct experience: it is in fact to do with reaction time, where the aim of the game is generally to become as proficient

as possible in reeling knowledge out into action, in the two senses of knowing the rules, and knowing the moves, where the time of the shot is modulated as and in the form of the inner experience of the player and players. Where this forming of our inner experience goes unnoticed because it does not wind up into the pure knowledge Bergson names, that we have called cinematic contemplation, until it breaks down.

(Like the following clip, but backwards.)

- Honda ad, 2009