moving image: theory | context: lecture 9

VFX is the art of contingency. We have been considering the time of contingency.

For the mise-en-scѐne time is the condition of a character’s embeddedness in a time of contingency, where anything can happen, which, for us the viewer, is the time of historicity. Our first concept.

We look at the clip and see time as it is passing for the character, whose ‘inner experience’ of time provides that schematic link and is the principle of their animation.

For what we are considering now, modes of form, time is the pure contingency to our own historical embeddedness. This mode of contingency is the thing in the shot that was isolated, its mystery or aura. Isolated and giving rise to genre: knowledge of genre, which is what to expect, is like a framework for the modulations in the shot.

We are looking at developments, at the developments of form in the medium of the moving image, and in digital media in general, inasmuch that the moving image medium is central to digital media.

In the first half of this course, modes of contents; in the second, modes of form. The common factor being modes: characters as modes, then what might be called technical modes, the technical modalities of moving image production. Including VFX, SFX and CGI. Not limited to them because starting from the shot and its time which replaces for us our inner sense of contingency: we are now historically embedded, socially, economically embedded and embedded in technology, the discourse of technics, when and this is the most important word, when we are plugged in to screen-time.

When is that? Pretty much full time. Like now, for instance, watching this lecture, plugged into the time of it. Embedded in it? Not at all. When is it? When is it taking place?

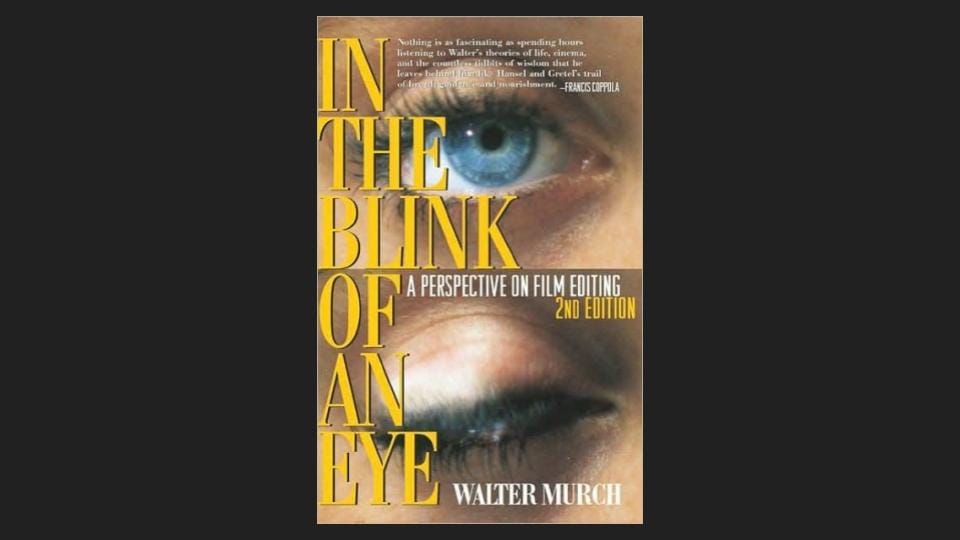

And have we any guarantee it is? None at all. Because what we take for granted is the mystery here, the aura, the shot: We don’t register the contingency constantly modulating this shot; if it cut here, would we notice? Or would it happen, as the best book on editing has it, in the blink of an eye?

If you’re at all interested in editing, I recommend you read it.

Plugged in by the screen into screen-time, we take for granted that which cinema’s early audiences paid to see.

So what is modulating this shot of me speaking to you? Reading, in fact, a lecture? That I am in a room.

You might say, you recognise this genre: you know about it. It’s a room.

It occupies 3 dimensions, and that dimension that is added on like an afterthought, that was central to Einstein’s whole work: time.

Are these assumptions made from the generic quality of the shot?

If I added a background, would this sense of the contingency in the shot evaporate? …

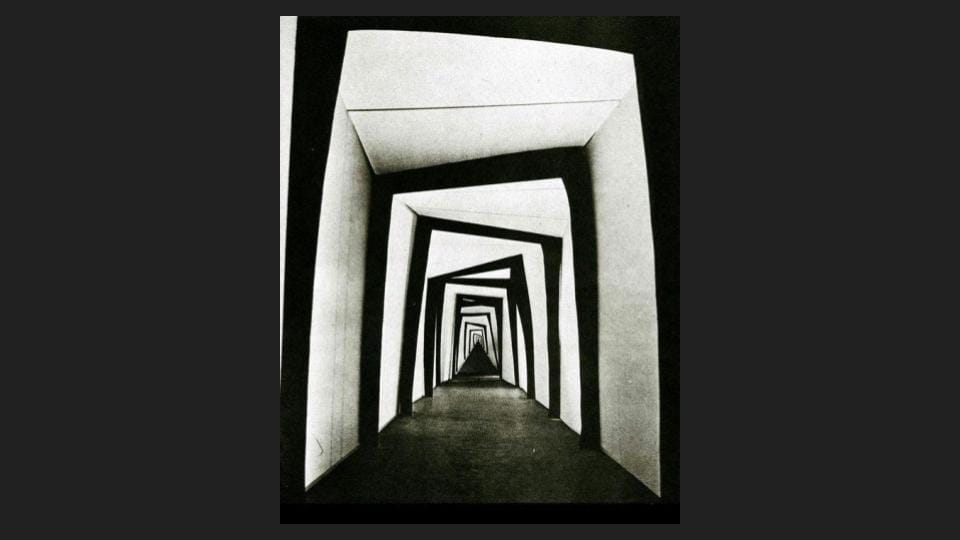

What I like most about backgrounds is exactly their generic quality: sci-fi; beach scene; generic interiors, with certain indicators as to class and taste-group, good taste equalling muted tones, off-whites, nothing rising to the shout of a primary or contrast… imagine for instance a background based on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari…

There is a Zoom background from The Shining…

…is classed a ‘funny’ background for meetings. It belongs then to comedy. Comedy is clearly how you show some personality.

From the website for the Amazon affiliate, Rigorous Themes, we get an idea of what is at stake in background art:

The site also offers virtual meeting etiquette guidelines and ground rules. Of most relevance here, this:

…with the essential piece of wisdom, When you begin on time, you can end on time.

You can just hide everything… carry on … without a care in the world. …

How could you have a care in the world, hiding it behind an asteroid from Star Wars?

At the top of the list on Rigorous Themes, with this completely unironic commentary: attend meetings while floating in outer space… and: “The big space rocks might even intimidate your manager and prevent them from asking you too many questions or prolonging the call beyond the specified time frame.”

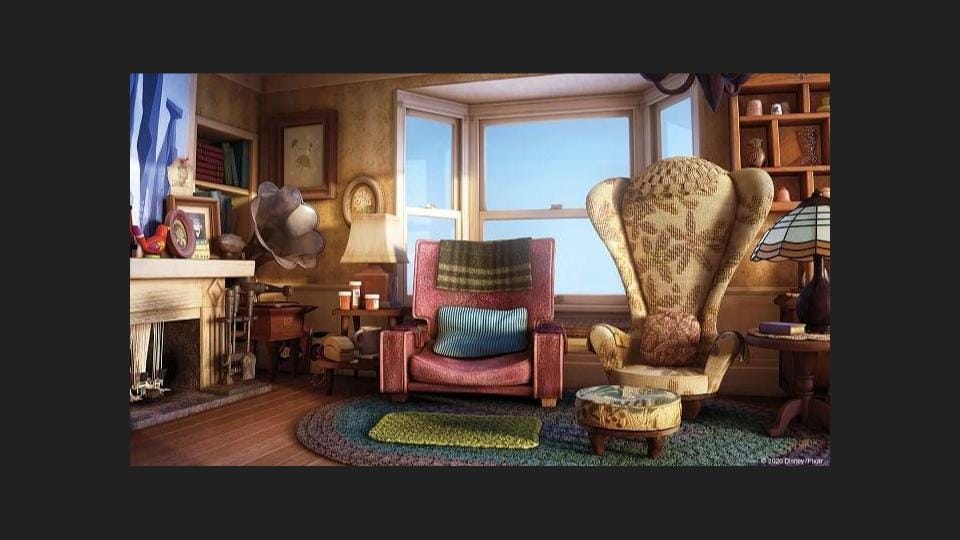

What about joining the cast of Up?

If you are worried about what this background might be saying, the comment is: “Anyone who doesn’t believe Up is one of the best animations to ever grace our screen should reconsider their tastes. With this awesome background, you can feel like you’re on the set of the movie.”

Does it need to be pointed out that, unless the cast is considered to be the actors doing the voice-over, Up is not a live-action film?

To feel like you’re on the set, what does this mean?

Not only should you reconsider your tastes if you don’t believe Up is one of the best animations ever to grace our screen, because you’re clearly wrong, you are being told it’s a good thing to feel like a computer animation, one of the cast.

Or…, you can star in your own mockumentary.

The next background is from The Office television series.

The advice given is, “do your best impression of Jim by turning away and staring at an invisible camera whenever someone on the call says or does something ridiculous.” …

Now, think about what we were saying in the last lecture about genre’s relation to knowledge.

Knowing Jim turns away and stares at an invisible camera whenever someone, someone in front of the equally invisible camera filming the TV series, we can imagine, says or does something ridiculous, that’s insider knowledge.

Rigorous Themes does not say, if you do this, not everyone will get the joke: imagine everybody thinking everybody else is saying or doing something ridiculous, all staring at invisible cameras… not at the ones you are, in fact, supposed to be eyeballing, according to virtual meeting etiquette, at the top of the screen.

It takes training to look at the visible camera… Think of little Andrée Lumière, looking down the barrel of the cinematograph in 1895, and holding the biscuit out to uncle Louis… while Auguste and Marguerite Lumière studiously avoid it…

Or stun your colleagues with this one.

Go in exactly the opposite direction to Architectural Digest, the arbiter of good taste in interior design… and, says Rigorous Themes, “See how long it takes for someone to ask you if everything is okay.”

Hilarious.

Then there’s the more predictable…

…to take, says the comment, “boring to magical” …

The soothing colours might even have a soothing effect, and help you recover from the stress of the day.

Is this real scenery? Is this the magic of nature? Or the magic behind the animated feature, The Good Dinosaur?

And does that matter?

In other words, why are we interested in these backgrounds?

For the reason of their unclipping from any sense of the time in which we are actually situated: they even reinforce the idea our mundane, meaning in-the-world, reality is boring and unsuitable for the medium of virtual meetings.

Be like Jim, stare off at an invisible camera. Join the cast of Up.

After all, it’s your performance, you are the principal character…

…plug into the time of the mise-en-scène; unclip from the uncertainties, the challenges, the circuits of indetermination, which are the contingencies of your actual historical, economic, social and technological existence.

Plug into generic life.

Plug into Second Nature, the one we take for granted from our acquired knowledge of generic life. …

Or, rather than joining the cast Up, why not join the Second Life family?

Second Life, launched 2003, going viral right away.

Its founder, Philip Rosedale, with money from Mitch Kapor, founder of Lotus, and Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, holds out hopes for a revival, perhaps Third Life?

…

The conclusion to the article showcasing the best Teams backgrounds of 2022 on the Amazon affiliate site, Rigorous Themes, and, please note with me that these are not Riotous and Random Themes or Scenes of sheer abandonment, no.

They are Rigorous. Strictly following recognisable tropes, iconographies, techniques, settings, themes, belonging to genres, perhaps without the musical motifs…

…where your colleagues are characters and you are the star.

The conclusion to this article runs like this, “Whether you want to have a little fun with your colleagues, send them down memory lane, or make them wonder why you are the way that you are, you can find the perfect Microsoft Teams background to fit your intended purpose from the above options.”

I would call attention to this bit, of calculated revelation: make them wonder why you are the way you are…

Casey Riley, writer of the article, credit where credit is due, is a wife, mother and entrepreneur.

In her spare time, she enjoys traveling, language, music, writing, … and unicorns.

Make them wonder why you are … the way you are … the phrase “have a little fun with your colleagues” links, recalling Bateman’s multimodality, to Best Funny Zoom Backgrounds. At the top of that list, as if Casey Riley had curated it, is…

Be a real housewife.

The best of the best Funny Zoom backgrounds is a still from The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, which, the site tells us, “is a pop-culture classic at this point. The show has timeless replay value”... our point exactly. … “and everyone enjoys watching the characters squabble.”

…

The ideas of theory and context become quite redundant next to these truisms.

And the only truisms we can offer are these: against the inertness and curatedness and calculated meeting-strategy genericness of these backgrounds, I, you, we and our colleagues and managers, are the VFX, the contingent items, incidental to the moving image, like leaves, dust particles, of which the Brownian motion is proof of another sort of time.

…

We can’t leave this theme of themes without mentioning the Harry Potter background, the staircase at Hogwarts, with the title, Wingardium Leviosa, or this…

…Casey Riley tells us: Feel free… in this cartoon book rendition of the SHIELD office from the Marvel Cinematic Universe: …sounds pretty far-reaching… Feel free to exaggerate as much as possible and talk about “super secret missions.”

…

The Teams meeting strategy of Rigorous Themes, again, note the rigour, presented by Casey Riley, who enjoys unicorns, does not make any distinction between computer animation and live action.

Both are native now, and possibly have been since 2003, to the medium of the moving image. The site says it’s entirely acceptable to give yourself a CGI background. This has been naturalised by current business practice.

It has been naturalised under cover of being funny, or quirky, showing personality, you might say.

The weirdest one for me is ‘be like Jim,’ stare off at an invisible camera whenever someone does something ridiculous… but perhaps it’s not weird for you: in other words, perhaps you have the necessary generic knowledge; and in this case, it’s quite sophisticated: because what Jim is showing in the live-action comedy, The Office, is his awareness that he is being filmed; and this is scripted in: it’s not the actor making it up as they go along, as their personal ironic statement.

That is, it’s not an expression of the personality of the individual actor, it’s Jim’s character trait to do this.

We can contrast this with the quirky campy self-awareness of Johnny Depp playing Captain Jack Sparrow: was it scripted in that Depp, someone who’s currently playing just as ironic a role, albeit much cringier, in the courts, with Amber Heard playing it straight… was it scripted in, Captain Jack’s self-parody?

No. It’s a character quirk Depp cannot seem to get away from, it’s the actor’s own; as they say about fashion models, scarf is model’s own: in this case, self-parody is actor’s own.

With Jim, the fact that we can accept that it belongs to the character, so that Riley can say, ‘be like Jim’ in a business meeting, is because this ‘level of irony’ has become acceptable for comedy. Introduced by Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant, both of whom appear in the English version of The Office as actors, staring at an invisible camera is accepted to belong to the comedy genre.

How do we know this? Because we recognise what is happening when Jim does it; when we pay attention to what we are paying attention to, we recognise how this action has been absorbed by genre.

…

Genre knowledge is the channel giving permission, to corporate employees as to serious academics and their managers, to use as backgrounds either live-action scenery or that produced digitally, without distinction. Who cares?

…

When it comes to contingency and, I would say, the discussion of VFX, it’s not leaving behind the ‘real’ space for the digitally fabricated one that matters so much as leaving behind, or unclipping from the real time, the sense of time in which we are actually situated, by plugging in and plugging into a generic background.

The choice of background, that Riley says shows my personality, replaces it with a time of noncontingency and a time in which I don’t really have a choice, because it is determined, not historically, but generically, according to known categories of taste and the recognition that others have when they know I know.

This is control modulation: what about if I choose an obscure indy work for my source of personal imagery?

Well, it’s not obscure. It’s one of the most famous works of the indy genre. And, it’s great how actor John Lurie would be kind of sneering down at you if you used it as a background.

What points would you score in a corporate meeting with this background? Would using it, as Riley suggests, mean having a little fun with your colleagues? Would it send them down memory lane, and make them wonder why you are the way that you are?

Or is it, as they say, ‘a lot’? Too much.

Too personal: the wrong memories, going down the wrong lane, to make them wonder, why are doing this? And ask, Are you okay? For all the wrong reasons.

…

Your choice of Teams background is controlled to the extent it is socially modulated. But this is still a modulation: the contingency here is contingent on factors which we most often take for granted.

The contingency here involves shaping choice, the choice of what is shown. And this has to do with the isolation of the purely random in early moving images, not to control it, as different critics have said, but because that was both what those audiences wanted to see and what they would pay to see.

And from this we acquire a knowledge, from comparing what is contingent, from our enjoyment of these first random special effects: yes, in time, they become less special; we habituate ourselves to them.

However, as we have said, we sooner habituate ourselves to the material conditions of the screen, which entail that the locomotive is not about to bust out through it into the cinema and mow us down, we sooner habituate ourselves to the fact of the screen, than to what is shown, the experience of which we are plugged directly into, and experience at the same time as we experience it. Sooner the train than the waves.

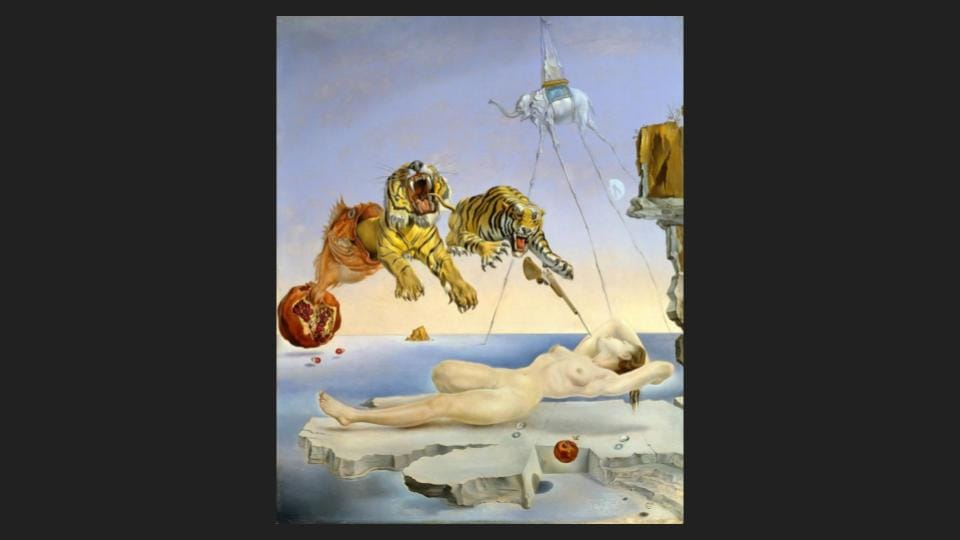

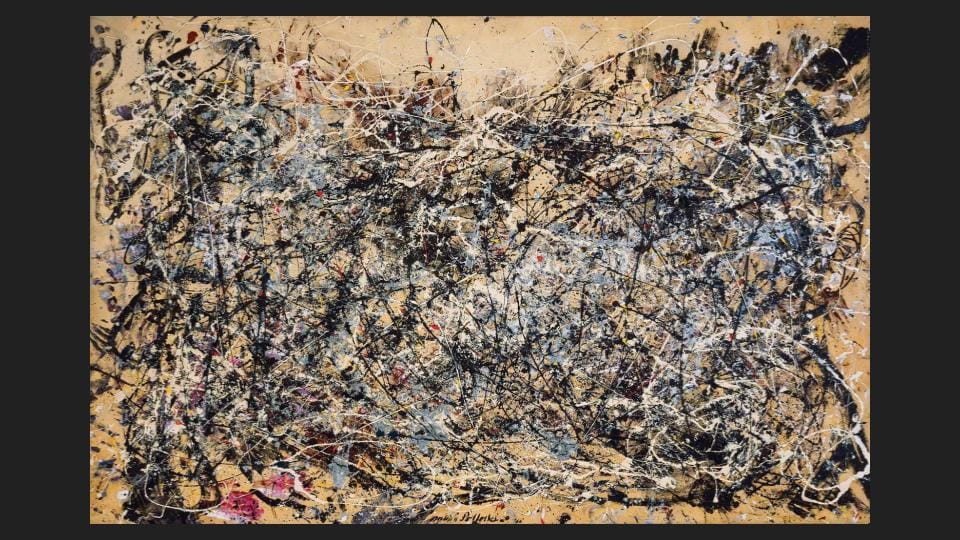

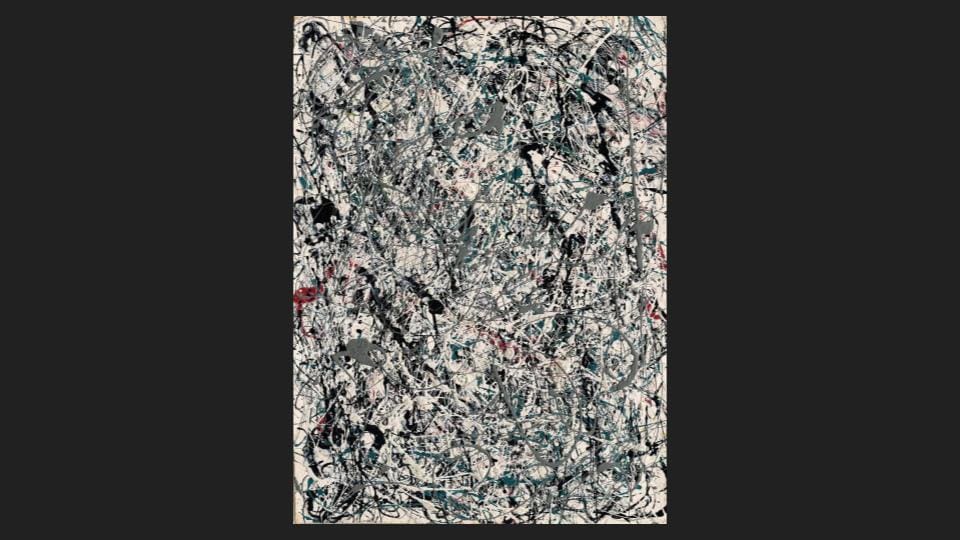

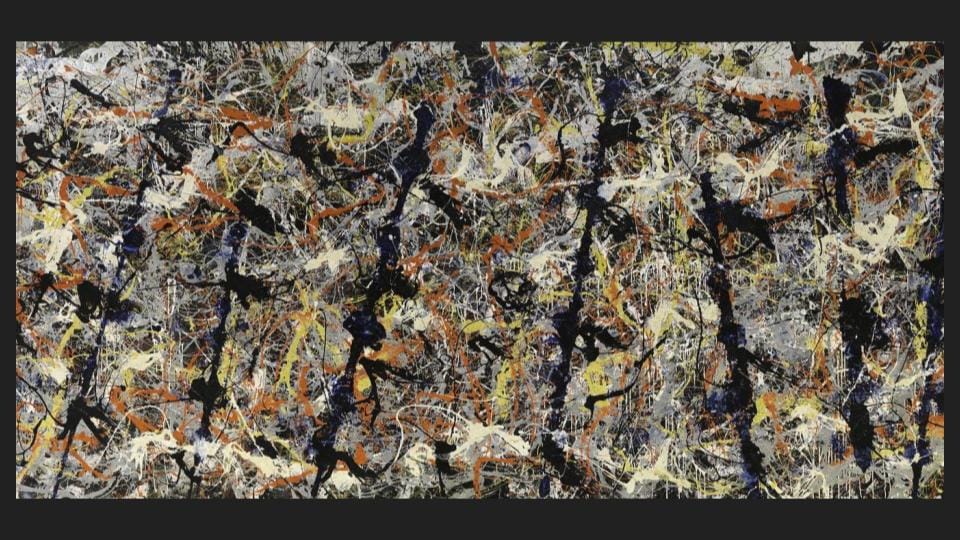

Or, if we think of painting, Jackson Pollock is harder to get used to than Salvador Dalí.

The fright or shock may be there at the start, with Dalí:

…but with Pollock how do we get our bearings at all?

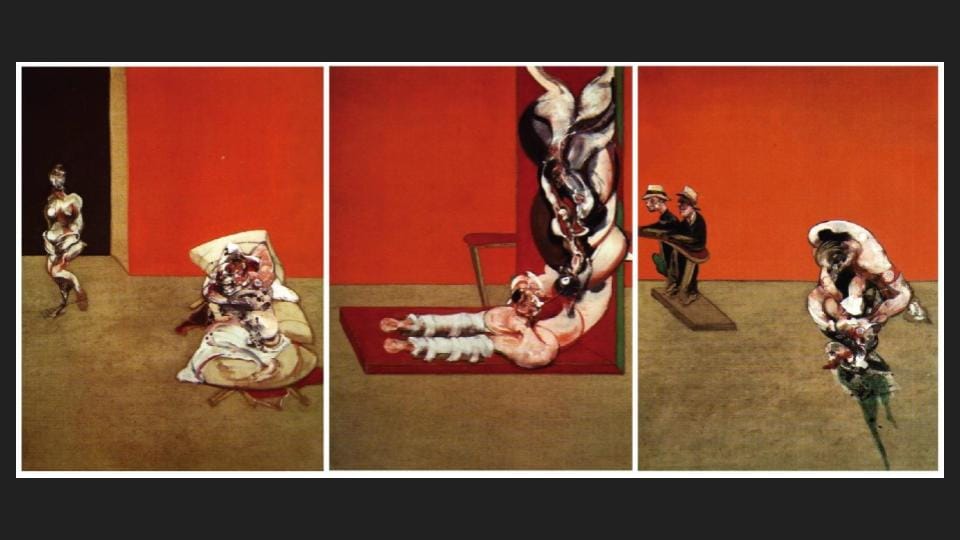

How about Francis Bacon?

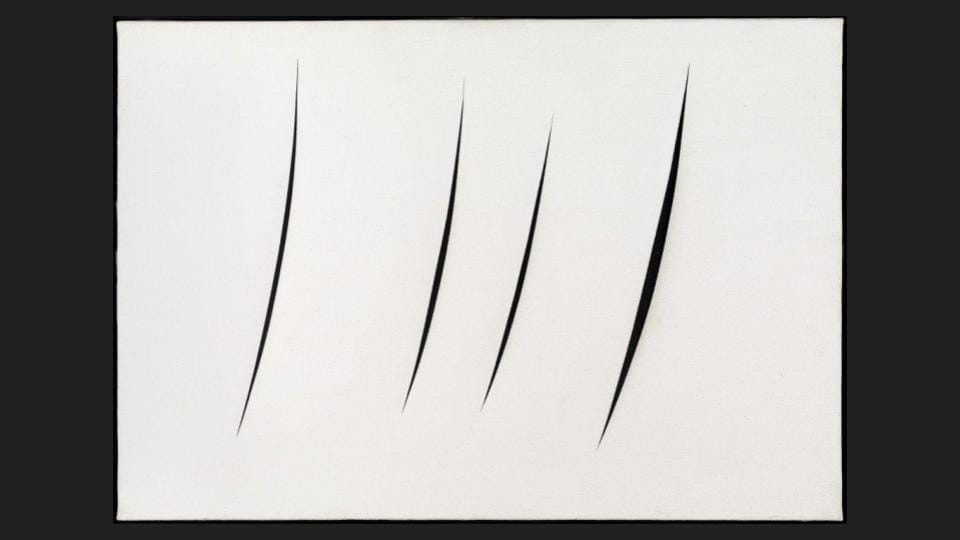

Or do these paint effects lead us into contemplation? Isn’t it, that reminded that the screen is just a screen, the paint is just paint, the support for the painting is no more than canvas…

Isn’t it the case that we look for what the work expresses? Or is this a representational quality, or category?

When we stay with a Pollock painting, interesting he called it Action Painting, we compare not what it depicts. And not what it represents, unless we’re art historians and looking for the historical narrative, what it represents for some kind of development or progress. But we compare it from work to work.

If that’s our thing, we go, Look at how the splatters change from the early to the later work.

We might even say, Pollock got better at it.

At what? Foregrounding the materiality of the paint?

No. At this mode of expression, in which, over time, from painting to painting, the work modulates.

...

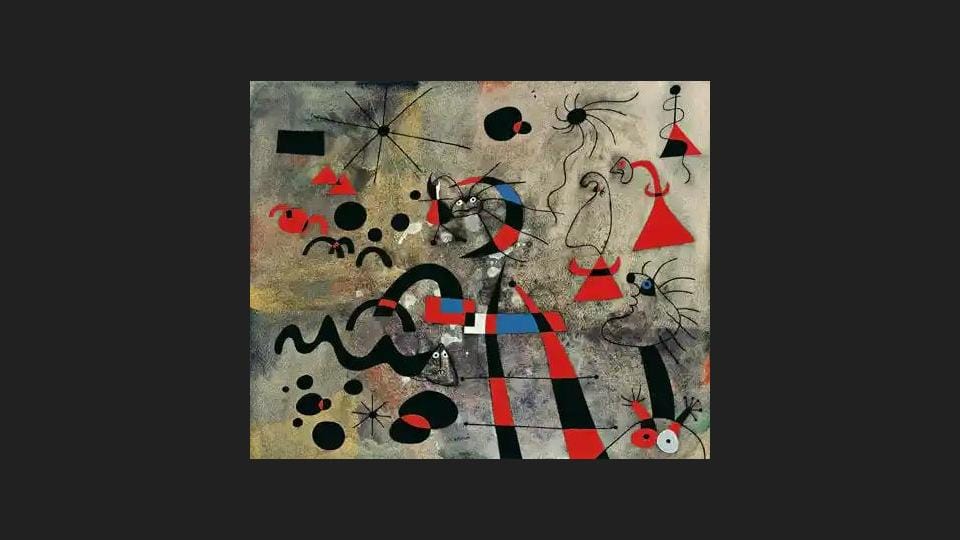

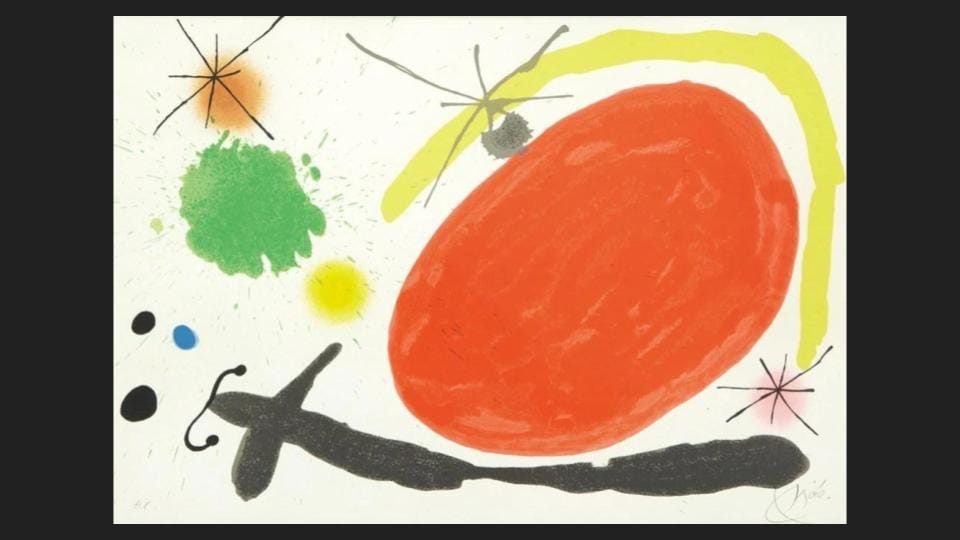

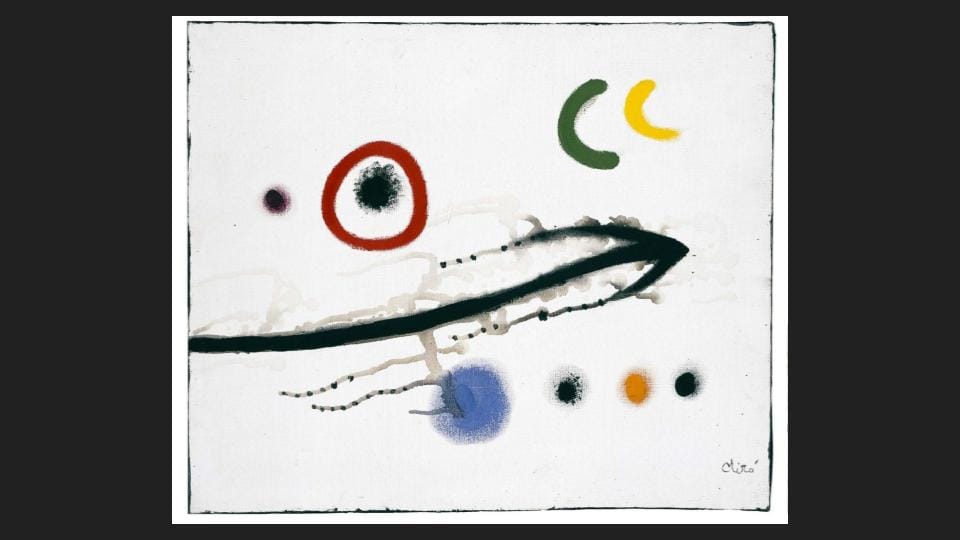

I’ll just mention one more painter, before returning to… in a way, I am dealing with visual effects here. …Joan Miró.

…whose work you probably know. It’s much more fun than Francis Bacon. Light. Even funny.

… and playful. And thought by some to be quite superficial. Surfacey. Not difficult enough.

Until we hear what Miró wanted to do. He wanted to assassinate painting. So he was like his best friend, Marcel Duchamp in this… Oh no, not another painter!

Not really. Duchamp hated pictorial arts. He wanted to get beyond what he called retinal art.

The art that hits you in the eyes. Or it doesn’t. In fact, it does nothing. It does nothing but appeal. And we say, Oh, pretty!

Duchamp wanted to make art express concepts. He had very sexual imagery for this, strangely. Because it sounds like such a cold thing, concepts…

He wanted the mind to grip the concept like a lover.

He also played with identity in ways extraordinary for his time, inventing for himself a female identity in 1920.

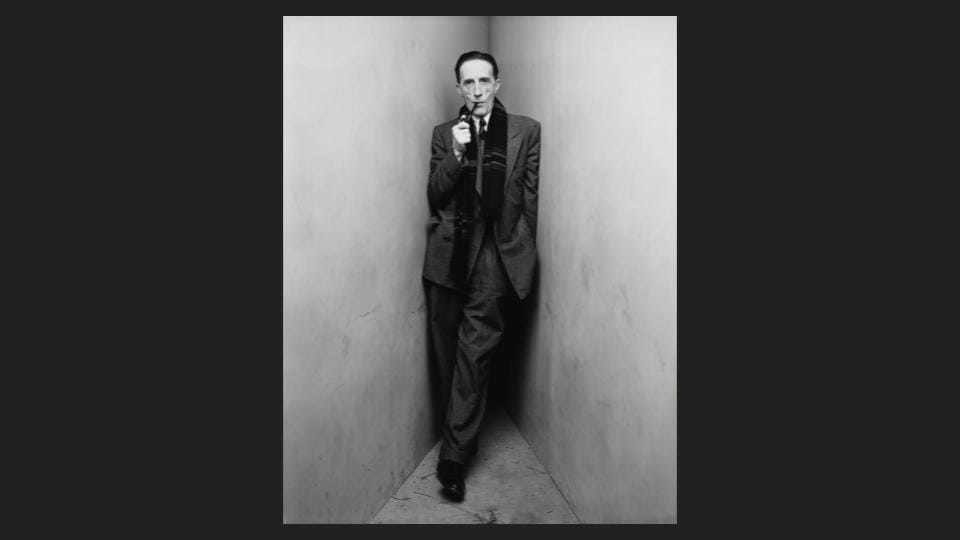

Here he is:

And as Rrose Sélavy:

Duchamp is much more famous than Miró for his destruction of the categories of art. All from this one work:

Entered into a competition in New York in 1917. Called Fountain. And rejected.

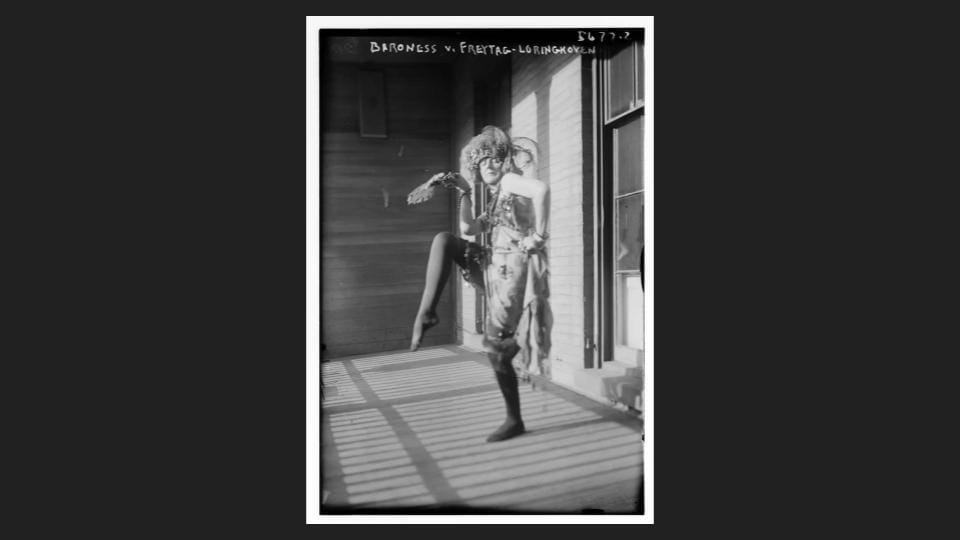

And as a side note there is evidence that this is Duchamp’s appropriation of someone else’s work: he stole it. From Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Here she is:

More famous for her style of life and dress… she wore sardine cans in her hair. Not always clean ones. …than for any art she made.

…

Miró’s assassination of art was carried out by breaking out of painting from inside it.

For the purpose of his paint effects, he used the materialities of paint and canvas … to do what? Introduce exactly the dimension we are most concerned with here: time.

He made a mark on a canvas and rubbed or scumbled it… until, yes, it acquired an aura: and he sometimes called these scumbled points stars.

Stars because they seemed to extend the canvas into its depths and come from somewhere distant, not in space, but in time.

No longer quite paint. No longer canvas. Something else.

Something coming from millions of light years away.

Or ago.

So his paintings’ assassination consisted in what you see on some kind of transparent surface, like a projected image.

His spontaneous lines project out from the plane.

They are spontaneous … immediate, playful and joyful. Because, millions of years behind them, is an endless depth. An infinity of night.

Against which they are in relief dancing like little lights. For a moment. Then gone.

…

These experiments in art, in painting, belong to the same trajectory as film, cinema. And the moving image. But what have they really got to do with VFX?

Everything.

Because of what VFX do. We can happily say they assassinate film. In the most playful and superficial way.

We have to go back to our leaves to understand this.

It has to do with the image freeing itself from the material conditions that produce it. From the materiality of celluloid and then CRTs and then flat and plasma screen technologies, from the screen where we see the images, the images dance in relief like little lights, transparencies, which project beyond the materials. We may know how they’re made, but what we are trying to account for here is what they do.

Same with Pollock’s splashes of paint: the action that made them is important; but how do we see the images?

No matter that we are told, for Pollock, it’s all about the paint itself, its viscosity, and colour, the materiality of it, what we see is immaterial, not material at all. And this has nothing to do with representation.

Same with Bacon: what we see is a special visual effect, more or less compelling, more or less horrific.

And the place this image which separates itself out for us from the material conditions of its productions, where is it?

Well, it’s not really in space at all.

As a distinct phenomenon, which, we remember, simply means appearance, it is in time.

Is it in our time? The time of our experience? Our inner experience? Inasmuch as we plug into it, yes. But something else has happened. Is happening now.

Something that is not time passing, since it’s screen-time, cinematic time, that passes. And can leap 2.6 million years. Or reverse. And repeat.

In other words, what we have been saying about screen-time goes against the laws of physics.

Freed from its materials, the image unclips from us; as we unclip, plugging into it, from our own materials.

The simplest way of saying this is what we spoke about in the first lecture, our first concept, historicity. Our sense of embeddedness in social, economic, historic and technical time. And the sense of that embeddedness we attribute to characters, who, in their mise-en-scène, are shown to be both embedded in that time as well as to link to another sort of time, the time they experience in their inner lives.

The minimal condition of character. The schematic. Animation, and so on.

What the leaves moving on the trees show is their unclipping from historical time. No longer embedded in the time it takes the wind to blow, in what we might call natural time, the leaves, the smoke, the waves are free. Freed from historicity. From historical time passing.

In them, our experience of time changes too: we grant images a freedom we don’t have. We deny ourselves.

We deny ourselves to have the freedom that was for Bergson the result of our material condition: as bodies with elaborate nervous systems.

Bergson wasn’t talking about cinema. That’s important.

So his view of images is still to do with the image in time and his conception of time remains that of its inner experience.

From the beginning of the history of the moving image’s development, note that it is moving, from the beginning, the moving image has captured the indetermination we find in nature. That is, the indetermination that is contingent on our material conditions.

Freed from those conditions, the moving image, the indetermination in the moving image, wants to have more and more noncontingency: this doesn’t mean it wants to be controlled; its contingency, its randomness, its being incidental, the leaves on the trees, the dustclouds from the wall, the waves breaking, is its noncontingency, meaning, the moving image is no longer reliant on either fluid dynamics, or physical laws of any sort.

It’s not a contradiction: the contingency of the moving image wants an increase in noncontingency.

How? How does it itself want it? On its own? Without actual bodies helping? Writing the software programmes, producing through painstaking effort the effects of hair being mussed randomly by the wind? Reproducing effects taken from nature, out of a desire for … perfection.

Perfection is of course the absolute noncontingency of contingency.

Ideally, AI is responsible.

And the AI that can handle this is on its way.

This is what Elon Musk is afraid of: he says he sees a world where humans are under the existential threat of machines. Sound familiar?

What has this to do with VFX?

VFX is the how. Desire is the why. Both in the sense of commercial incentive. And in that desire of audiences and producer-audiences, audiences who produce for themselves these effects, related to genre, from the point of the Wave Genre on: to ratchet up the experience, prolong, amplify and intensify it. And to accelerate it.

The acceleration bit means faster, for example, rendering times for 3D-modelled objects, settings and characters.

The prolongation we can readily understand: 45 seconds of screen-time may be enough, but if you’re really digging it… well, those early audiences were happy simply with the repeat, with repeating the experience. And also, those 45 seconds were enough to make the point: of a sort of time freed from historicity.

And the amplifying and intensifying the experience? The thrill of bigness, in all respects.

A big explosion. Make it bigger!

Make it so that if it happened in reality it would have killed half the population of New York but only caused our hero to raise an eyebrow.

A big spaceship. Make it bigger. Space is very very big.

Make it happen in a galaxy “far, far way”...

Make whole planets explode.

The tech? Make the guns more powerful.

And the superpowers of the alien race? Give our own guys super-super powers … Oh, and to ratchet up the tension, a key weakness:

At the last minute she was torn: would she turn back for that chocolate bar, or save earth?

Put more and more at stake: well, that’s narrative effects. But it’s supported all the way by the development of VFX, CGI, mo-cap…

King Kong. Stop-motion. Metal armature…

…foam rubber and latex body. Rabbit fur.

Four models built to scale. Otherwise miniatures. And rearpro. If we think of acceleration, 7 weeks spent on the T-Rex fight. Also a miniature.

1933.

- King Kong, 1933

Remade in 1976. King Kong is robotic.

In fact, animatronic, like the wild animals at Disneyland.

Full size for key shots:

…like holding Jessica Lang.

The 2005 remake: King Kong is Andy Serkis. With digital double. Motion capture used throughout.

And the fur: a ‘photo-real fur system’ able to work with 30,000 to 40,000 independently moving clumps of hair.

This system has become known as Barbershop, and is still being developed. For hair. Fur.

Kong 2005 is a completely computer-generated moving image. Not only that, the jungles are CGI and the New York that appears in the film is fully digitally generated.

But does it have anything on this?:

This is from Epic Games, using Unreal Engine 5, released this year.

Of course, we want to pause with the name: unreal, as in, that’s unreal! Meaning it’s super-real.

And in games we see this tendency: we’re not so interested in the character; we’re particularly interested in the contingent, what we’ve been calling the contingent: the incidental… We want the movements of characters to be super-real, and what is contingent to their bodies, like hair, whether they breathe or not, we want that to be super-real too. Do characters in games breathe?

We’re interested in the surfaces and textures and … in the effects.

…

Would we really find a less real and more unreal gaming mise-en-scène less immersive? Would it engage us less to the degree it showed a less realistic environment?

This is a question that goes back to genre: sometimes the slickness, the degree of perfection attained, is not the point.

And, once more, we need to consider what perfection means, because of what it means to us, and our desires to play the game or not, to see the film or not, to stay watching the clip our friend sent us, or not.

What this has to do with genre is all that knowledge we have, not of what reality is, but of what it should look like.

Because we can see in that Unreal Engine 5 work-out for Superman what we have been missing, and may even choose to miss, from lesser game systems.

It’s ‘unreal,’ sure: but we might want to spend a few solid hours playing old arcade games.

We see the advance in the tech because of our knowledge of this particular aspect of its development, in genres: our knowledge of VFX.

We don’t go looking for it in dramatic or arthouse movies. But it’s there too.

In the film Birdman for example, 2014, directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu. All the way through: VFX is used to sell the idea that the film is shot in a single take. And, in some ways, less obviously, for the protagonist’s alter-ego, who flies. Hence the title, Birdman.

Flying characters we’re super used to, so accept.

But a feature shot in a single take: How did the camera do that? Travel on a dolly, then give us that bird’s eye view? Then go to the wide without cutting? And then, and then…? We might ask.

…

What do we see in the development of VFX from 1895 to 1933, to 1976, to 2005, to Skull Island, if we stay with Kong, a couple of years later, in 2017?

We see the tech’s already dated. Even from 5 years ago, the visual effects look a bit dated.

… But what dates them is precisely the dependence of these effects on the material conditions of their production, conditions which include the digital components of the studio.

…the aim of these digital components is perfection. Meaning the complete freedom of the digital moving image from the material conditions: its not being contingent on, meaning reliant on, the state-of-the-technology.

A reminder: the meaning of historicity is social, economic, historic and technological embeddedness. From which VFX aim to work to free the moving image.

…

We also see an advance, as if there were here a perfection to get to: when, what we’ve been saying is, it was there from the start: it was the leaves are moving on the trees.

Already perfect contingency in its noncontingency, in its unclipping from the historical time, the historicity in which we are, on the other side, embedded.

...

So why think of this as progress? To achieve realistic hair or fur effects? To achieve realistic hair or fur effects, which, when we get to 2005, counts more in the history of VFX than the impression created by a giant ape!?

What is set in train by the moving image, the moving image is the most basic fact of the digital era, what is set in train is the auratic contingency that is there from the first.

And what happens to the leaves happens all along the path, from 1895 to 2017, to 2022, this auratic chaotic, stochastic motion, is isolated.

It develops according to the motivations of two factors: audience desire to see, and pay to see, and the commercial incentive. But it’s always double, and often backfires: what causes a flop at the box-office?

Producers thought the world needed another Marvel franchise film, but it was one too many, perhaps.

There was nothing new in it, nothing modulating that already existing knowledge audiences had acquired about how the Marvel universe works.

Always two: first comes what you want. Then, it’s not as if you have any choice. Unless you actually do…

That’s a matter to take up in the next lecture, but we’ve already hinted that whatever the progress made by Unreal Engine 5, you might prefer to go retro.

…

So we isolate VFX as a mode of form that modulates our desire to see stuff and pay money to, or to play games… That calls on our knowledge, and adds to it.

Then what is the advance of VFX really towards?

Knowledge? Yes, but what we wind up into pure knowledge it would reel out into unreal action…

What we see in the development of VFX is the co-optation of every contingency, all the way to the totally immersive ‘reality,’ that we cannot distinguish from our lived one, of virtual reality. And when we get there, what will we be saying?

The trees in that virtual reality scene were so real, the leaves were moving on them! …and the grass, and the hair… I mean, the leaves were blue, but we were on a different planet, yo.

Is it pointless, then, this advance? Depends what we want. And depends on what we want.

We can say, however, that it exists: it goes to the studios and studio systems being built which don’t need sets for the live-action characters, because the sets in every aspect of their mise-en-scènes are CGI.

Bad news for the fabricators, and set-dressers, and art departments used to dealing in real objects, architectures and properties; bad news for the scenic artists who go around, after a set’s built but before it’s dressed, adding patinas of use and wear and tear. Spraying on a bit of rust, aging up the new things supposed to look old, adding, Benjamin would say, aura.

And VFX goes all the way to the entirely animated worlds we’re used to from gaming and Studio Ghibli, in which everything and everybody is a visual effect of some kind, from the cels and other techniques of early Ghibli, to Earwig and the Witch, 2020. A computer animated fantasy.

Have a look:

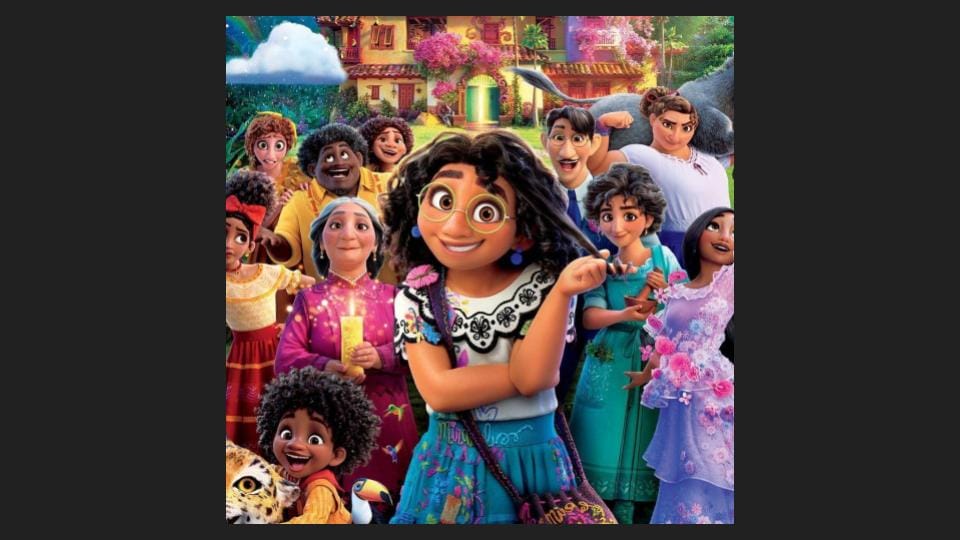

What’s typically Studio Ghibli, and Hayao Miyazaki is credited in the planning stage, is the detail in the settings and backdrops, the historical detail, and the care over textures around and behind the characters. But with the characters, director Goro Miyazaki (uh-huh), takes a different path to that taken, for example, by the directors of Encanto, 2021, Bryon Howard and Jared Bush.

Just looking at the hair, even in a still, is enough to clinch it.

Now, Earwig:

That’s simply for effect, you might say. There was never intention in Earwig to have naturally frizzy, springy, loose, strandy, messy, or life-like hair. But that’s my point.

Ghibli retains the house style of their animation: simplifying characters, exaggerating some qualities, eyes and eyebrows. Hair and hair colour. Putting all the detail into the mise-en-scène.

Where computer animation meets character we see two contrary movements: what sells character is the fact of their having an inner life, a principle animating them, which we have linked to another sort of time than that expressed by the mise-en-scène; while modes of form, like VFX, are sold on their degree of contingency.

Hair modulates: did audiences go to Encanto for the hair? Some did. But it was the characters that held them, teeming with contingencies which can never be brought into visual effects.

To be free on the inside, isn’t that the lesson of so many films?

And for Earwig … perhaps Ghibli went too far along the path of reducing the schematism of the characters, making them too real on the outside, and not real enough on the inside.