the painter of mental scenery

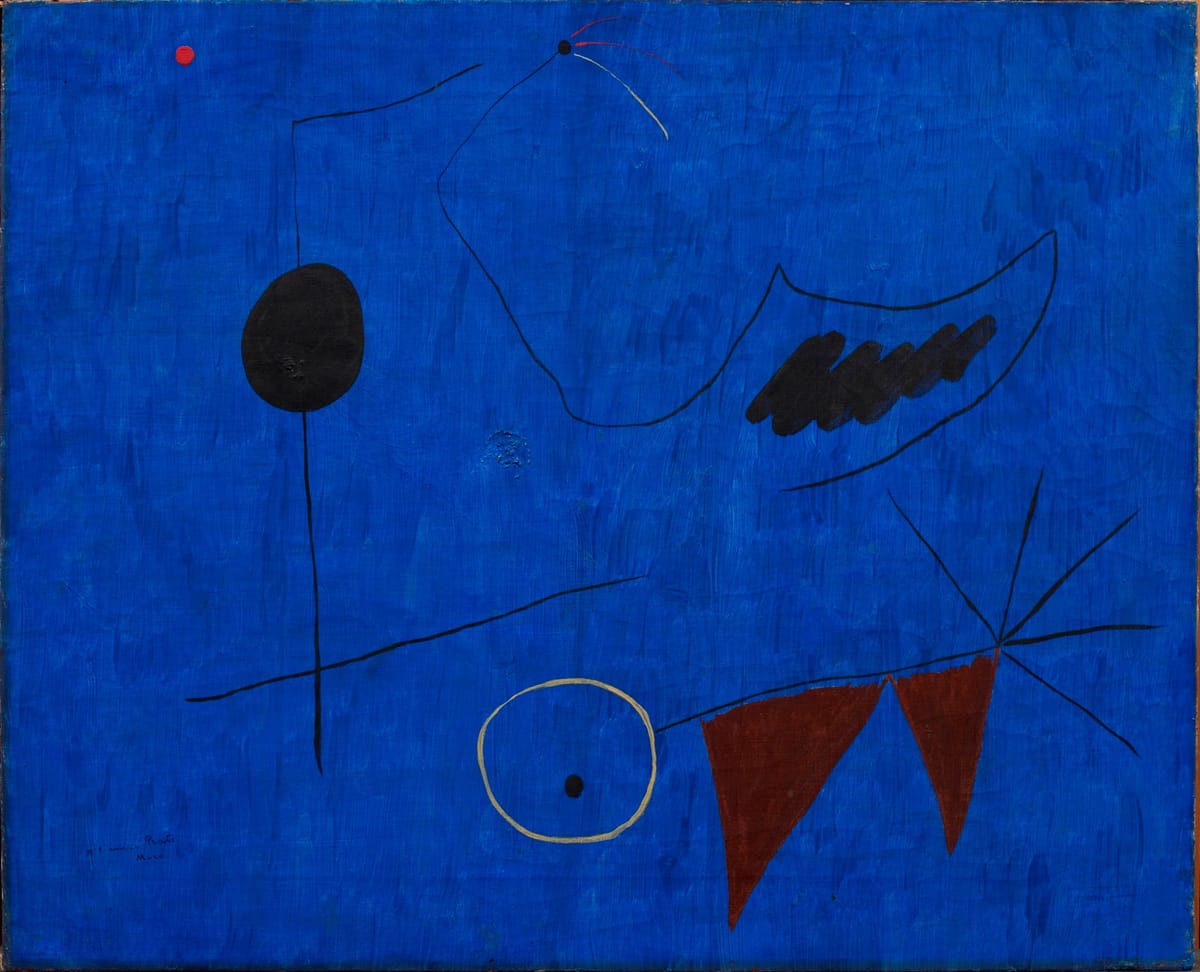

The title comes from Bergson's Matter and Memory. (Translation, N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer for Zone Books, p. 170; the online searchable copy p. 69 (yes, they pack a lot in).) The title recalls Baudelaire's essay "The Painter of Modern Life." (see links) I read it while preparing my master's thesis on dandyism, Nihilism, Cosmetics and Audacity: Dandyism and Dorian Gray, which I notice is also available through the online library at University of Canterbury, with an abstract I wrote but no longer recognise, that makes it sound quite fun. ... the painter of mental scenery also recalls Joan Miró, who is not so easily dismissed as a painter of decor when you find out, as I did while researching Duchamp for the play based on his work, Sweetheart, Over____, that, like his friend Duchamp but by other means, he set out to assassinate painting.

Miró's Pintura, meaning 'painting,' is reproduced above. Like Constantin Guys for Baudelaire, who directs painting away from so-called academic subjects, away from decorative art, towards the unassailable reality of contemporary life, assassinating its subject, Miró assassinates painting by presenting the unrepresentable reality of inner life. It's quite funny that Bergson calls this scenery; however something further links Bergson's subject to Miró's: chapter 3, whence this post's title, concerns memory and mind. It is a time belonging to mental life distinct from duration, which Bergson saw duration as the fundamental insight of his philosophical career and which he lays out in Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience, 1889, its title in English and many other languages given as Time and Free Will. (Please see links to both English and French versions here)

The French title not only more accurately represents Bergson's subject but also bears on that here, so far, of overcoming the representable, tearing down the scenery and assassinating painting, through its relation to Étant donnés by Marcel Duchamp. The immediate givens of consciousness, données immédiates de la conscience, are those in the act of being given, étant donnés.

The date given here corresponds to the presumed date of completion. The work was begun, it is presumed, 20 years earlier, when Duchamp had given up art for chess, completed in secret and only discovered the year after Duchamp's death, in 1969. ("the second room, Maria" and "the third room, sleep" both allude to the conditions of the work's production.)

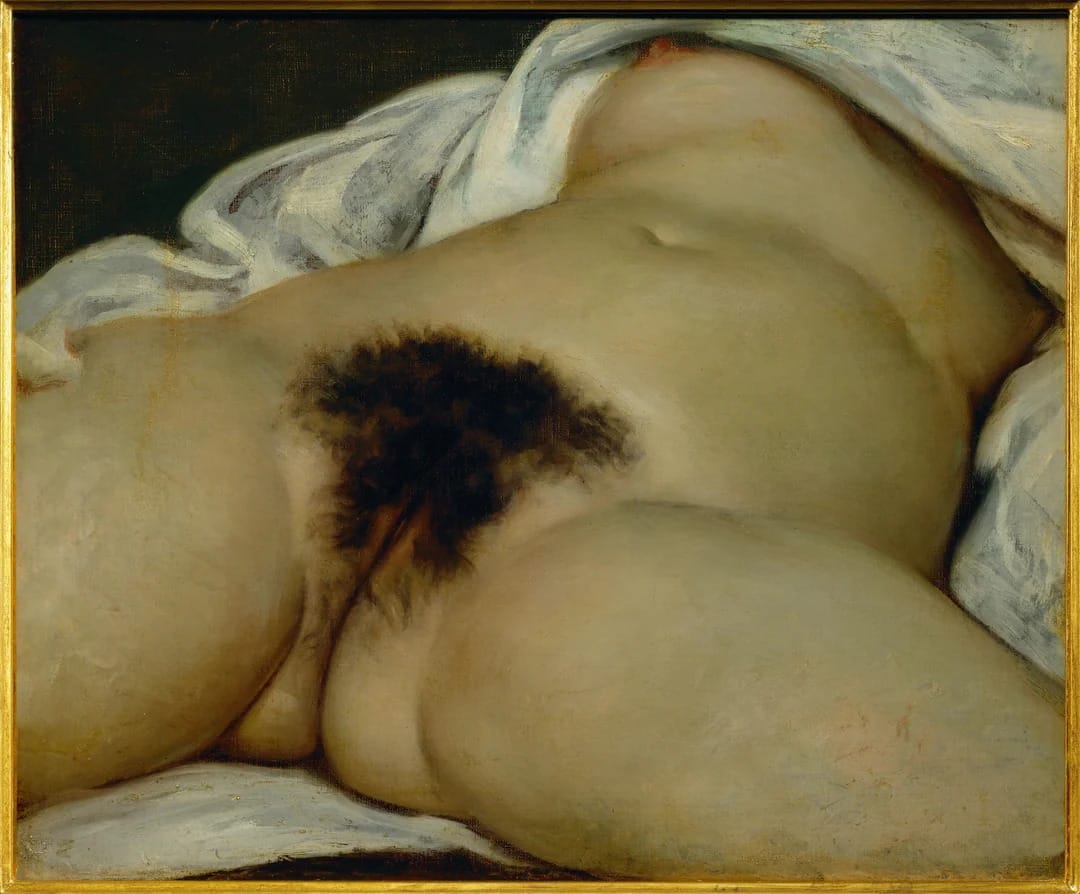

What does it mean? What are the 'givens' of the title and how do they assist or resist meaning? I assay one reading in "-ages of women & men: fashionable taboo & diabolical totem, a split between hairs". I will briefly try another.

I caption the image in that earlier post as a partial view of the work. So too is the picture above. In fact, the work is a construction of partial views.

Like Miró, Duchamp was concerned with time, he delays our arrival at it, while he restricts our view or constricts its opening out. As Elena Filipovic shows, who gives its full title, you approach Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage via a portal in the gallery wall at the Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art, where it is installed. Duchamp while working on it produced extensive notes on its construction, along with photographs of it which resemble a mise en scène. Together they amount to an instruction manual, both enabling its dissassembly where it was in situ at Duchamp's hidden studio in New York, and its reassembly and correct installation at the gallery. These notes and photos of curatorial instruction, Filipovic's interest is as a curator, have been reproduced in a book, which is really quite a beautiful object, a sort of double for the work itself.

The double-door, a portal because of this, weathered and old, is from another time. Michael Lüthy points out there is also, as it is installed, lit only by the light coming from the entrance into it, an intermediate space, a foyer preceding the portal, which provides its staging and intervenes before it, like a theatrical foyer. Many don't recognise the door for what it is and leave. The majority of critics and commentators, Lüthy says in "Étant donnés as a Form of Experience," leave the foyer out of descriptions of their experience of the work.

Those curious enough might try the door but it doesn't open. Twin peepholes, double like the door, that Filipovic tellingly compares to a fissure in her intellectual armour, give a glimpse, across the intervening gap, onto a hole in the wall.

Through it we peer onto a scene said to make us voyeurs, and, as in a theatrical foyer we might discuss our impressions with others. The erotic cast of the scene both discloses and withholds, while it consummates the gaze, it postpones intellectual consummation. Or, again, is said to, because our gaze is met and held by what Gustave Courbet, with the signature difference indicated in the earlier post, called the origin of the world.

This is only the given of the given; or the surprise of it being no surprise, we might say, in a formulation that goes with Duchamp's love of puns, for example his Rrose Sélavy, the name of his self-portrait in drag, giving Eros, c'est la vie; or the more obvious L.H.O.O.Q., title for a Mona Lisa with a moustache, Elle a chaud au cul or, harder work, the English, look, because with some transposition Étant donnés gives Dons étonnés. In English—surprising gifts.

Étant donnés – Dons étonnés

Dons is used in French for supernatural or spiritual gifts, the étonnement of which, having a sense that goes further than the English surprise, only amplifies it. We might say it is astonishment at the world, or, in French echoing its origin, surprise face au monde.

Then the actual gifts are numbered in the full title of the work: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage.

The first given is a waterfall. The second is gas lighting. Both are represented in the work by kinetic or special effects:

- the waterfall uses a light behind a slowly spinning perforated disc to appear to sparkle;

- the gas light is what in a mise en scène would be called a prac, a practical working light-source used in addition to cinematic scenic lighting or theatrical luminaires—it is nonillusionistic in effect, but in fact, electric not gas.

To describe the device, the mechanism, does not describe the effect. The effect does not resemble its origin or source. The light is a super-natural effect for the artwork because, part of the artwork, it illuminates it; yet, one light does not resemble the other and the work is not fully illuminated by the prac, the gas light.

In addition, the waterfall sparkles. The sparkling of the water as it falls is not captured as it was in the past in order to reappear in the present but is being given in the present. The gift keeps on giving, which is not, I would say, a riddle, but what it has to do with time:

- the present in the act of being given, which should be, although it's not always, a constant source of surprise;

- the nonresemblance of that source from its effect of lighting up the present from within.

Put another way, 1. we have the openness of the work to time, and 2. a coming forward of an earlier time, over time, that sustains the work: an origin that does not resemble itself, for example, a memory recalled, now in the present, the content of which bears no relation to what it had in the past. Gifts that being given astonish us, Étant donnés sont dons étonnés.

The detour returns us to Miró. His work too is lit up by an interior light. And this is what it has to do with time. The canvases are profoundly open to time. In some of them he uses the effect of scumbling, as if, in their long transit, the stars of the arrière-plan, the background, or, more precisely, at the back and behind what is being represented, have, meeting the atmosphere, attesting to their celestial source, acquired a haze around them.

In Pintura the sky is clear. The figures rush forward and have a playful innocence. Miró said that as he grew older and older his work became more and more infantile. It has more and more the gift of surprise and being astonished at the world.

We know this to be a learnt response, as well as an unconscious one on the part of his paint. MoMa cites his method:

Rather than setting out to paint something I began painting and as I paint the picture begins to assert itself, or suggest itself under my brush. … The first stage is free, unconscious. But the second stage is carefully calculated.

–source (cf., for artistic calculation, Stupidity, Idiocy and the Problem of Evil)

I don't know whether the translation is entirely accurate but note the play of tenses. Miró began painting. As he paints the picture begins.

We know that in the early 1920s Miró turned from painting what was before his eyes to what was behind them, his mental scenery. Why? a dissatisfaction perhaps with literal figuration but also the influence of figures, Duchamp among them, from the French avant-garde into Barcelona in the years 1916–1918, WWI nearing its end, who congregated around the gallery owned by Josep Dalmau, at the Galeries Dalmau, which closed in 1930. I visited, before it closed in 2024, the Sala Dalmau, founded in 1979 in tribute to Josep Dalmau.

A painting of 1925 gives full expression to the turn inward towards mental scenery. The first in Miró's new style, he envisaged it as a sort of genesis (cit.). It is called El naixement del món, The Birth of the World.

I suppose what I have to say is that the world keeps originating. However it would be a mistake, following the parallel, to consider what is adult content in Duchamp, if it is to carry out his stated intention of assassinating painting, to be child-like in Miró. It is innocent if it is only to paint mental scenery. Or, worse, if this is thought of as psychological disclosure—an intention all-too-readily imputed by the literal-minded to Duchamp. The scene becomes really bad once the x-rays are shown by The Guardian to reveal that Miró painted Pintura over a portrait of his mother.

The present is as in Pollock in the action of painting. In his book on Francis Bacon, Deleuze says something odd about this, he says that the painting in Pollock is all diagramme, the painting suffused with itself, in its own materiality, but for us here, it is suffused in its own action, which, in the present tense, is in the present. Then there are Miró's calculations, his, in the more common sense, diagrammes of figures and objects which live, where they are unrepresentable, in his imagination.

They resemble writing on the painting's surface. Their meaning has been lost, and the light from stars, is equally distant from and as indifferent to the marks, in Pintura and in The Birth of the World, as it is, although separated from them by tens of thousands years or more, to those earliest made marks on cave walls, on stones, on a comb, which Miró's also resemble.

The figures assassinate representation. The stars, by marking over time that loss of meaning, puncture resemblance. The painting, withholding recognition over the breach of the time that intervenes, marks the loss of any personal association for what is calculated or for what it suggests of human memory in general.

The painter of mental scenery, writes Bergson, has to take care to stay on a level of memory that maintains the consistency of the work. (p. 69) There are infinite levels between two extremes. At one, the most contracted, at its highest degree of tension, it's all action to which memory is called on to respond. At the other, at its most relaxed and expanded, memory is answerable only to itself. The extremes are the ones Miró names as the first and second stages: one is unconscious and free, I began painting; the other is calculated, the painting begins.

The painter of mental scenery has to observe the law which binds the degree of tension of the memory systematically to the different tones, Bergson writes, of our mental life. He continues,

... every one is clearly aware of the existence of these laws, and of stable relations of this kind. We know, for instance, when we read a psychological novel, that certain associations of ideas there depicted for us are true, that they may have been lived; others offend us, or fail to give us an impression of reality, because we feel in them the effect of a connection, mechanically and artificially brought about, between different mental levels, as though the author had not taken care to maintain himself on that plane of the mental life which he had chosen.

–Ibid.

It sounds like good advice; the exclusive use of the masculine gender notwithstanding, it also sounds old-fashioned. What if the author sets out to offend? to shock, even, knowing that the shock will make it memorable? And Bergson does have something to say about this. He writes that there are holes in the levels where a shock has torn away the surrounding memory; and therefore there are also memories which stick out and support those around them,

... shining points round which the others form a vague nebulosity. These shining points are multiplied in the degree to which our memory expands. The process of localizing a recollection in the past ... consists, in reality, in a growing effort of expansion, by which the memory, always present in its entirety to itself, spreads out its recollections over an ever wider surface and so ends by distinguishing, in what was till then a confused mass, the remembrance which could not find its proper place.

–Ibid.

Bergson implies that the whole of our mental lives are given between the two extremes of action and, what he cannot call pure memory because it is all memory and so he uses dream to symbolise memory at its lowest degree of tension, dream. For a writer, then, it is good advice to maintain oneself in the scenery of a level that constitutes a surface reality because of the alternative. The alternative is that the peaks or shining stars exist as isolated individuals—and this does nothing to explain the holes—and can be wheeled into a scenery for effect: they are either meant to confirm a surface in its reality by breaking through it or the surface is so tightly woven of association that they shine above it, to no effect, without connection, or with an effect that is only mechanically and artificially obtained. Bergson calls associationism the assumption that psychological reality comprises the individual data of experience, that come to be linked only, that is fortuitously, by experience. In this way his theory of memory is consistent with duration. Duration is the system, whether it pertains to subjective or objective experience, uniting the data, like a number of notes, to which it gives its singular tone. (see also here)

Yet Bergson insists, when it comes to memory, on both association and contiguity. I have struggled with this chapter, with Bergson's presentation of memory, for reasons that are general, for example, memory being absolutely independent of matter (p. 72), and those, particular to me, in relation to my theory, based in practice, of perception. This is that perceptual attributes are infinite and definite in the role they share with imagination of creation. Perception and imagination are not exclusively human attributes. Biological perception is something we share with trees, in the imaginative multiplicity of processes of embodiment, and of our individuation, I write in a tree imagines it's a tree. While I conceive of machine-perception as being that work which is the practical application of AI, which I talk about in human virtual multiplicity and AI’s singular expectancy, being constantly mistaken for something else, namely thought. "We are allowing the proliferation of a technology which will not destroy humanity but will destroy its thought." deals with why: we attribute thought to AI and then wring our hands about the threat it poses, when we are not expending too many words on it, because thought, and not perception, is supposed to be our defining characteristic.

Spinoza only allows access to the human perception of two of God's infinite attributes, but he saves himself, and philosophy, according to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, by making the attributes of thought and material extension expressions. Their modulation into individuals continues the expressive and expansive imaginative flows of God, or, since Spinoza allows this, Nature. However we know two.

What suggests to me an insufficiency in this account is the exigency placed on practical work by it having to account for itself as thinking or else be relegated to a lower rung, like the body is to the spirit, and matter in general to the immaterial. You see Spinoza presents both the problem and its solution, at least part of it, and Deleuze and Guattari follow up by allowing carpenter's to think. The philosopher who does away, in the most radical way, with humans being special because of the specialisation of their God-or-Nature-given brains, is Zhuangzi, 莊子, for whom the butcher is perceptual paragon, his knife always stays sharp because through it he feels the spaces between the bones that would blunt it and the flesh which he cuts. Better then: his knife is sharper than the perceptual tools of logic or of science, since these are only species of knowledge. Neither the butcher has any use for these, nor does the sage, nor should, Zhuangzi suggests, the Emperor Wenhui—and yet all do practical work, where often the brain and what is in it are an obstacle not an asset.

Bergson's part in this theory of perception, of infinite perceptions, of access to them and of their expressions, is played, in chapter 1 of the same book I am having all the trouble with, by his conceiving perception as being outside. Perception and every image in which it is expressed is outside, not then a psychological fact or one of mentation, not conditioned or part of the brain's performance, not gated or restricted by our senses, by the inadequacy imputed to them. Internal representation, consciousness, occurs without necessary concurrence with the material imagery that is outside. The difference is due to that between sensation and perception: if a perception does not from the start form a sensation associated with it, Bergson writes, it is unlikely ever to. We remember the sensation.

Bergson qualifies this by saying a sensation recalled need not have the same association at all as it did in the memory. The evidence he offers is that under hypnosis a subject may be told to feel hot, they will in turn feel hot, but not because there is any heat in the word. We perceive heat in the word, equally, by an attunement to its primary association, that is active in and of practical use for what we may call poetic perception. Of course, it is highly impractical in logic, despite both using words and being expressed in words, and here we can claim there are further perceptual attributes that use words and other signs, of symbolic perception. These are irreducible to association.

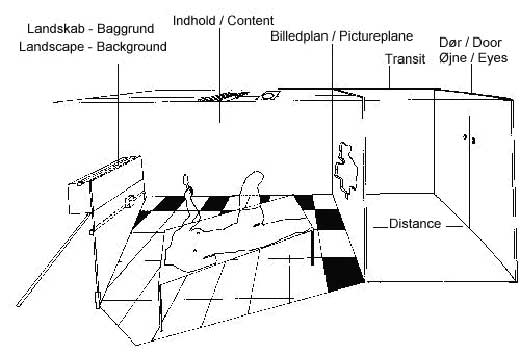

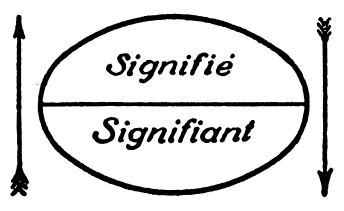

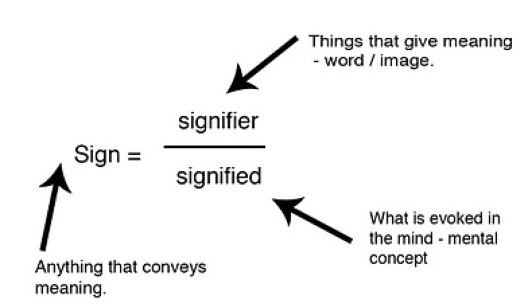

That is, they are falsifiable by association. Jacques Derrida, Luce Irigaray and Julia Kristeva show how the modulation of meaning across perceptual attributes, from metaphysics to physics, although expressed in words, can lead to their claims, rather than serving themselves, serving against, and deconstructing themselves. Usually, as if it were exploiting a loophole, this is attributed to the general state of language, and expressed in the form of a law which Ferdinand de Saussure is said to have discovered: the bi-directionality of and split in the linguistic sign. In diagramme form:

In English, with the terms explained:

In other words, no matter how tightly woven meanings are, between signifié and signifiant there is a space, a gap, a fissure. We might, in the context of all that has been said, say that it is a creative interval; for the purposes of internal critique, it allows a space into which what has been excluded may flow, for the critique of phallogocentrism, the feminine.

In the light also of what has been said the difference between the French and English terms is of note, particularly as it concerns the tense and temporal nature of the parts speech. Signifié is the past participle of the French verb signifier and signifiant the present participle. Signifié therefore denotes a completed action (and what Bergson in chapter 3 of Matter and Memory calls its termination in an image); while signifiant designates continuing action (which for Bergson, requiring only the intervention of memory, has been there from the start): one signified, the other continuing to signify.

I had thought this to be the purpose of memory. And it is, but in a way I had to wait to grab hold of. Bergson twice refers to an ingenious theory he finds we cannot support, which is that when we dream there is a split, comparable to that above in the sign, in the body between movement and sensation. Letting go of its function as a centre of action, the body is released into pure sensation. Earlier I talked about hypnosis: the hypnotic subject gives evidence of how sensation, and therefore the internal associations formed by sensation, which are what we remember, can be falsified. The word hot is not. Bergson's use of the example is to another end. It is to refute the idea in psychology of the path from perception to memory being direct and not taking the detour of a present sensation and its prior association.

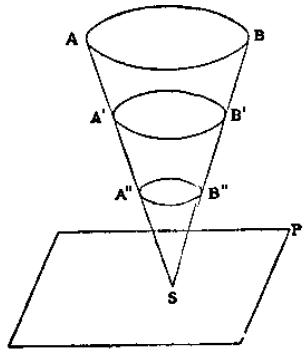

If all that we remember are associations then that is the sum of our mental life. The pointed end—I am referring to the famous diagramme of the ice-cream cone, light cone or record stylus, by which Bergson depicts the body connecting perception with memory—may be in action, but in continuing to act we are more puppets of associations, some, from the start, some learnt, which is where contemporary psychology dominated by CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Theory) puts us. More than having free agency, we are only free to dream. Dreams, Bergson repeats several times in the chapter, are powerless.

I have, since it shows the levels where the law of associated ideas determines the mental landscape, chosen the second of the two cone diagrammes. S rests on plane P. Associationism makes it an arbitrary movement up and down the cone. For Bergson, the whole cone, SAB, is who we are and in life we are either involuntarily or we place ourselves in between matter, P, and memory, A–B. He argues against the psychologists, who take one to be the other separated by a difference of degree, that they ignore and have put aside sensation when they talk like this, as if they are not alive and don't have bodies when they do; he argues, on the other hand, with philosophers, for whom memories are associated by resemblance and consolidated into levels or, we might (speaking post-cinematically) say, scenes by contiguity, that they cannot explain how, that they over-intellectualise, separating ideas from, since it is for the sake of action that they are chosen, the point of their selection, S.

The action of which these philosophers should be reminded is that of thinking: thought is a movement and always, although it would prefer and they would prefer it to have a direct pathway from perception, engaged with sensation. Bergson pulls perception back in from the outside, yet he still maintains the consistency with what he has said about its externality. His use of the term image is to steer a middle course: an image is neither a material illusion, a matter of suggestion and association, nor an immaterial idea, but a matter of orientation, and therefore participates in both movement, following the principle of action, and sensation.

In this, Bergson says, perception is enriched by memory, because, counter-intuitively, the point S calling on general notions, memory is where the details are. If close to the base, as Bergson calls it, since it is an inverted cone, at A–B is where we dream we are not among images of any second degree when we are there. It's just that there is no there, there. We are spatially unsupported and without the assurance that our sense of direction gives us.

To bring in another instance, where Bergson has to assert a discontinuity, to throw some light on the continuity that doesn't allow him to allow us to accept a break between the body's conditions of movement and those of sensation, that is in its sensori-motor unity, to occur when we are dreaming, the brain cannot be the container for memories. We might find the chemical vapour-trails, as it were, of past actions and from them conclude their general orientation, and perhaps using statistical probability, or AI, extrapolate from that, in the brain, but for Bergson they cannot be stored there. By making the brain a storehouse, he writes,

We forget that the relation of container to content borrows its apparent clearness and universality from the necessity laid upon us of always opening out space in front of us, and of always closing duration behind us.

–Ibid., p. 60

An opportunity long overdue reading this chapter, this gives me recourse to my work on cinema. As cinematographers of mental scenery, we are not subject to the same necessity, we are not the centres of action so much as we are the centres of scenes. We have for our orientation the virtual eye of the camera in a perception of content, within the bounds of the frame it has as condition, that is as detailed as we want to make it.

It's not the image of the brain as storehouse we reach for when it comes to memory, or to representing how and what we see when we turn our gaze inward. However, within that temporality, given by cinema that gives us our metaphor, there is no room for the other from which the first, giving us an altogether different problem, is captured. It has the characteristic of being the past to the present and only this allows us to escape its metaphoricity: from a certain point, S, we are looking back at the screen where the film A–B is playing. Or, for cinematic perception, through the actual not the virtual and metaphorical camera which acts as our point of inner orientation, the inverted cone is turned upside-down again and plane P is replayed as if a conical section were to be taken from a thousand layers of moving images.

No matter how many filmic layers are superimposed over each other, however, it becomes one imagery. The point is, moving—this is decisive: the cinematic metaphor of movement has displaced the spatial metaphor of containment; but something has been left out, sensation. This the actual camera doesn't do, it has to be added as a spatial effect, by cutting, bringing shots into contiguity using montage, and editing for continuity, that is, contiguity.

Can the same be said for cinematic imagery as for the ingenious proposal that when we dream sensation breaks free from what the body asks of it as a centre of action? Bergson accepts a functional relaxation of the nervous tension which grips the body when called on to act, that allows it to dream, but not a separation. The reason I think is that sensation prolongs movement rather than completing it. Both are external in perception and one externality, unless there is space for them both, cannot coexist with another.

What makes me think there is none? Both are images. In the case of their superimposition both are past, as noted, and replayed, together, it is a single sensation which prolongs them, and gives rise to the associations which are drawn back (or down) from memory. Three points follow from what Bergson has said:

- the whole of the past coexists with the present (the trouble I have in this chapter is that Bergson uses personal memory to talk about the past in general);

- sensations terminate in images;

- memories expand into images (Bergson introduces states of the past which correlate with the different levels in the cone diagramme, easily imagined to be states of consciousness).

Gone from consciousness in this account of memory is the zone of indetermination, which is its biological and material condition, of an interval given by the complexity of the brain and nervous system. It is what we might call, if the process is open, processing-time. The nerves transmit sensations from the periphery of the body to the centres in it, including the brain, to select from them what is of interest. This is the only time we are free, in the zone, Bergson says, before it is determined, preceding action.

Although perception occurs in it, we seldom experience ourselves in it. When we do, it is usually as the result of a shock or an accident, and all of a sudden what was thought solid is not. We have no recourse to familiar associations. We are certainly out of the way of habit and in this pre-conscious state may not recognise what is happening or know what we are doing. Only after will it be known, remembered as a singular event, with all the details leading up to it, or not: if we cannot process it in time it will tear a hole in memory or even rip our memories apart.

Shocks like this do happen, particularly in the time when our memories are forming, when we are children. The virtue of Bergson's account of memory is that it shows how pathologies of the memory and personality disorders can share an etiology in bodily trauma. In fact they are inseparable. Most evidently in the case where we don't have the image of the body to anchor us or when it no longer can, psychosis is experienced not as a loss of reality but as a feeling of unreality, a dream from which we can't get free. In the case of trauma ripping memory apart it's easy to see how two, three, or more cones can form.

If memory expands into an image—and here we may think of the detail belonging to the pure memory image and the place of action where it is not one—that it's past must be key to understanding it. Memory is the condition for the forming of images. Images as they are formed must be so, as it were, by looking back over a shoulder. (This is something like what Deleuze describes happening with Aion, in The Logic of Sense, 1969. Chronos is the Great Wheel and Aion an infinite straight line from which, nonetheless, a shaving of the present curls up and, behind it, is taken into the past.) This would be consistent with memory's predominant feature, that is in the past, but not, except if it were an illusion and it is no illusion, with, memory being absolutely independent of matter, its immateriality.

Here there is a difference with duration, where the past is coexistent. The past coexists with the present and we are unconscious of it. Most of the time we, as Bergson says, close the door to it behind us, in order to be getting on with whatever is ahead of us. Unlike memory, it exists materially: we are, writes Bergson, as unconscious of it as we are of the other rooms in our houses beyond the one we are in; that doesn't mean they're not there. Yet Bergson is using this very solid metaphor for our personal but past conscious states. They are other rooms the existence of which we should not doubt. This solidity for something meant to be immaterial bothers me, and at a certain point reading the chapter, I decided that all Bergson had left us with was the network and the police.

Because if memory is the past that lets images form which are also in the past, there is the law and our level of action is completely predetermined. There are no new images. And if associations are all it's made of, or on, the networked space of connectivity has taken over from spatial contiguity: the brain may be an image among images but that image is of a network. There are no open windows in networks.

I read a passage just then from a novel, Philip Pullman's The Book of Dust, 2025. Lyra is reminded of something she has forgotten, that isn't named, that she knows is important, but has forgotten. In other words, it flickers at the edge of her imagination. It's like those chemical vapour-trails I mentioned: you can see it points to what left it but not what that is. Miró's foreground figures flicker in the same way, orientating us to something.

It's curious that Bergson uses these words for memory, of an attitude taken towards a specific memory, and of placing oneself in a memory. Although most commentary identifies the virtual with memory I think it's in the choice of these words, which describe a bodily, and no doubt a biological, disposition, conveyed by a tiny action, or the whisper of one. You have to know where to look, at another place in the same novel, Lyra is told, out the side of your mind.

In this light, memory is that which assures space and gives rise to spatial imagination. It is the part of duration turned to space; the spatiality of memory provides the immaterial grounds for Bergson's insistence on association and contiguity. The material image of the body as a centre of action is also orientated in space, being absolutely independent of matter, by memory. Once we have defined space by memory we can see how images which use memory for their layout, to coordinate their organisation and order both the social and personal spaces, from where sensations terminate, become spatial determinations. We also see why, memory itself presses forward, gnawing at the present, Bergson writes, to insert the largest possible part of itself into the present action. On the one hand, this has to do with determined knowledge, the images of which are pre-formed and the organisation of which is spatial; on the other, it has to do with power, power over that which can be stored up, contained and controlled. Yet it is also this assurance that memory holds for us and keeps safe, in the flickers of the virtual and in the coexistence of the past. Memory tells us we are heading in the right direction, and this in fact is forwards, when everything else tells us we are heading backwards.